Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

The Role of Networking Capability and Relational Capability to Increase Marketing Performance Through Utilizing Business Process Agility

Redi NUSANTARA1*, Vincent Didiek Wiet ARYANTO2, Yohan WISMANTORO3

1Ph.D Faculty of Economics and Business, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, Indonesia.

2Faculty of Economics and Business, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

3Faculty of Economics and Business, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

Received Date: January 20, 2023; Accepted Date: January 25, 2023; Published Date: January 31, 2023;

*Corresponding author: Redi NUSANTARA. Ph.D Faculty of Economics and Business, Dian Nuswantoro University, Semarang, Indonesia. Email: p42202200005@mhs.dinus.ac.id

Citation: Nusantara R, Aryanto V D W, Wismantoro Y (2023) The Role of Networking Capability and Relational Capability to Increase Marketing Performance Through Utilizing Business Process Agility. Enviro Sci Poll Res and Mang: ESPRM-125.

DOI: 10.37722/ESPRAM.2023101

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the role of network capabilities together with relational capabilities in improving marketing performance through the use of business process agility in construction companies in Central Java. The research method was carried out quantitatively by collecting data by distributing questionnaires through electronic forms and printed formats that were submitted directly to respondents where the respondent was a Director who worked in a contracting company in Central Java. The sampling technique was carried out purposively based on the criteria of the Director who had worked at least five years at a contracting company in Central Java. Based on these criteria, there are 228 company directors who have met these criteria. The data were analyzed using AMOS 22 statistical software. The results showed that networking capability had a positive and significant effect on relational capability and business process agility and marketing performance. Relational capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility and has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. Likewise, business process agility has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance.

Keywords: Business Process Agility; Marketing Performance; Networking Capability; Relational Capability

Introduction

Every company around the world is impacted by globalization. This globalization phenomenon is characterized by an increasingly high level of competition between companies, resulting in high uncertainty and dynamic socio-economic conditions. This condition is caused by the company’s desire to dominate the market and seize wider opportunities. However, although globalization encourages wider competition between companies and competitors who come from all over the world, high competition is actually the result of maneuvering between companies in the market, which is characterized by rapidly growing competition based on price positioning, quality, and resources (Toryanto & Hasyim, 2017). Therefore, the company becomes more difficult to maintain and control its market due to intense competition and unpredictable market due to hypercompetition, which is a condition in which the assumption of market stability is replaced by instability and constant change (Albekov, Romanova, Vovchenko, & Epifanova, 2017; Sultanova & Chechina, 2016).

To deal with all these things, companies must be more actively involved in creating competitive advantages through network development to boost the company’s ability to gain customer trust and increase profitability. (Luo, Hsu, & Liu, 2008 ; Gorina, 2016). In addition, companies also need to carry out network activities to obtain competitive resources from outside the company to overcome challenges because the single relationship that the company does cannot provide all the necessary resources. (De Leeuw, Lokshin, & Duysters, 2014). In other words, with this network capability, it allows companies to link their own resources with those of other companies by building relationships between them. On the customer side, relationships are an important means of studying customer needs and for developing marketable offerings. In other words, network capabilities can be used as a mechanism to anticipate market opportunities, leading to a more focused and market-oriented deployment of resources.

In general, the network includes a series of corporate relationships, both horizontally and vertically, with other organizations, be they suppliers, customers, competitors, or other entities including relationships across industries and countries. These networks are made up of ties between organizations that are enduring, are of great strategic importance to the firms entering them, and include strategic alliances, joint ventures, long-term buyer-supplier partnerships, and a number of similar ties. In the business context, it is called a business network, where a business network can be defined as a set, two or more connected business relationships, where each exchange relationship is carried out between business companies conceptualized as collective actors. (Anderson, Hakansson, & Johanson, 1994). Connected means the degree to which exchange in one relationship is contingent on exchange (or non-exchange) in another relationship (Cook, Emerson, Gillmore, Klepinger, & Mullendore, 2013). What’s more, two relationships can be directly and indirectly connected to other relationships with which they are related, as part of a larger business network. The business relationship function can be characterized in terms of three important components: activities, actors and resources.

From the description above, the purpose of this study is to see how far the influence of the company’s networking capability affects the rationality of capability to create business process agility, so that all of this will have a significant impact on improving marketing performance.

Literature Review

Networking Capability

Capability is an integrative process in which knowledge-based resources and tangible resources come together to create valuable outputs. Therefore, ability is often defined as a form of skill and knowledge accumulation that allows companies to coordinate activities and utilize their assets, where this ability arises through the integration of employee knowledge and skills.

In general, networking capability is defined as a company’s ability to improve its overall position in the network (with respect to resources and activities) and its ability to handle individual relationships and to manage relationships between companies. In other words, network capability is the company’s ability to find network partners and manage network relationships to create a competitive advantage (J. F. Mu, 2014). This understanding implies that networking capability has two dimensions, namely finding network partners which is the company’s ability to identify the right individual or organization with which the company wants to interact. (J. Mu & Di Benedetto, 2012), and managing network relationships which are the relational skills of a company in navigating effective and efficient network relationships or establishing relationships with resource persons or organizations (J. Mu, Thomas, Peng, & Di Benedetto, 2017).

In addition, its networking capabilities enable companies to develop networks and gain access to network resources that are essential for product innovation (J. Mu & Di Benedetto, 2012) . Therefore, companies with higher levels of network capability tend to have more access to market intelligence than collaborating partners (J. Mu et al., 2017). Thus, network capabilities can play an important role in creating a competitive advantage that allows companies to coordinate a specific set of activities in a way that provides the basis for competitive advantage in the marketplace. Therefore, networking capability can also be interpreted as the ability to build, manage, and utilize relationships (Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014; Ritter & Gemünden, 2003) or close relationship with external parties (Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014:Jamil, 1998), ability to interact with other organizations (Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014;Gianni & Andrea, 1999) and the ability to find, develop and manage relationships (Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014;Lambe, Spekman, & Hunt, 2002).

Networking capabilities also suggest that organizations need to develop the ability to adapt, consolidate, update and reconfigure resources to take advantage of and take advantage of opportunities generated by a changing business environment (Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014;Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). In addition, network capabilities also assists organizations in acquiring and exploiting critical resources that span organizational boundaries for product development that aligns with customer and market needs (J. Mu & Di Benedetto, 2012;Vesalainen & Hakala, 2014). Therefore, networking capability is needed by companies to improve their competence in order to establish cooperation and interact with other stakeholders. With the improvement in the company’s network capabilities, it is hoped that the company will be able to increase its competitiveness in the market.

Relational Capability

The relational capability approach is a theory that discusses inter-organizational management (Pagano, 2009;Rungsithong, Meyer, & Roath, 2017) which seeks to explain alliance partner strategies to modify organizational routines to achieve effective integration and higher partner performance (Pagano, 2009). In general, it can be said that relational capability tends to be intangible, relatively rare, difficult to measure, and difficult to imitate by competitors, so that it cannot be replicated by companies that are not bound in a relationship. (Srivastava, Fahey, & Christensen, 2001). They are mostly embedded in organizational routines, which are repetitive activities that companies develop to deploy resources such as network relationships more effectively (Heimeriks & Duysters, 2007;Golgeci & Gligor, 2017).

Gianni & Andrea,( 1999) describes relational capability, which is the organization’s ability to interact with other companies in order to accelerate access and transfer of knowledge for companies that can have a relevant effect on company growth and innovation (Gianni & Andrea, 1999;Combe & Greenley, 2004). This understanding illustrates that high relational capability implies that partners involved in business exchanges can obtain information about the existence of relationships better. In addition, relational capability can improve a company’s ability to communicate, coordinate and manage business interactions (Jacob, 2006;Paulraj, Lado, & Chen, 2008). Finally, relational abilities are generally associated with facilitating the development of trust and dependence (Sivadas & Dwyer, 2000;Smirnova, Naudé, Henneberg, Mouzas, & Kouchtch, 2011) increase trust in the relationship and readiness for further collaboration.

In relation to the company, the company’s relational ability will involve a deliberate and organized exchange of ideas and experiences. For this reason, if the company’s relational capabilities have been created to generate large mutual benefits, the company will be encouraged to expand collaborative activities to facilitate market development activities. Company-specific resources can be utilized, shared and enhanced only if there is an adequate level of intimacy between organizations. It is well known that the transfer of a firm’s resources, knowledge and capabilities can increase the efficiency of its organization (Yan, Zhang, & Zeng, 2010).

Business Process Agility

Business process agility has become one of the main research interests of scholars and practitioners (Chen et al., 2014;Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011;Tallon et al., 2007). This is because business process agility is required to respond appropriately to a dynamically changing environment which is critical to the survival of the company (Kale, Aknar, & Başar, 2019;Vagnoni & Khoddami, 2016). In addition, agility can give companies the ability to quickly and easily improve business and business processes to effectively manage unpredictable external and internal changes (Van Oosterhout, Waarts, & Van Hillegersberg, 2006; Chen et al., 2014). The business process agility construct was originally developed by Raschke, David, David, & Carey, (2005) which is defined as the ability to add and or reconfigure business processes quickly into the form of business process capabilities. to accommodate the company’s potential needs.

The components of business process agility include reconfigurability, responsiveness, flexibility, employee adaptability, and a process-centric view. Reconfigurability describes the ability to develop new and modified functionalities/activities to build more adequate business processes. Responsiveness is an aspect that adds a timely dimension to reconfiguration (Heininger, 2012) . Flexible refers to the ability to instantly change the order of activities in a business process (Raschke et al., 2005). Employee adaptability is an aspect that determines the ability of employees to adjust their work behavior, as well as the attitude to do so, if the environment changes. Process-centric view where this refers to management’s view of the organization’s business processes, namely the organizational structure (Raschke et al., 2005).

Business process agility is very important for companies to anticipate or respond to changes quickly and easily (Van Oosterhout et al., 2006). In addition, business process agility is an important mechanism by which firms interact with the market environment, and can explain performance variances between firms over time (Van Oosterhout et al., 2006 ; Raschke, 2010). By prioritizing the speed and ease of the company’s reaction to changes in the market environment, agile business processes are expected to help companies achieve cost savings. In addition, they also enable companies to take advantage of opportunities for innovation and competitive action (Seethamraju & Krishna Sundar, 2006;Chen et al., 2014) Therefore, collaboration between departments is very important for organizations to adapt and meet market dynamics (Keszey & Biemans, 2017; Chen et al., 2014).

Business process agility is a rare ability that allows companies to redesign existing processes to quickly create new processes so that processes can take advantage of uncertain market conditions (Raschke, 2010) thus making it difficult for a firm’s competitors to identify which part of the firm is the most valuable. Therefore, business process agility is difficult to imitate and cannot be replaced. To conclude, business process agility has the characteristics of strategic organizational capabilities that can help companies to acquire and deploy resources better to suit the company’s market environment. (Chen et al., 2014).

Marketing Performance

Performance is a fairly broad concept, and its meaning can vary according to the perspective and needs of its users (Lebas, 1995;Alrubaiee, Aladwan, Abu Joma, Idris, & Khater, 2017). Generally, marketing performance is operationalized as a dynamic process that has several dimensions that are intended to be used to achieve the goals of the marketing organization (Morgan, Clark, & Gooner, 2002). Traditionally, company performance can be measured in accounting terms (Avci, Madanoglu, & Okumus, 2011). Performance is generally measured by many factors such as employee productivity, sales, market share, shareholder value, profitability, and customer satisfaction. On the other hand, performance can also be measured by knowing the extent to which actual performance is consistent with planned performance or with predetermined standards. However , Anderson dan Vincze (2000) argues that marketing performance standards can be set on the basis of the company’s mission, the company’s vision for the future (Alrubaiee et al., 2017).

Marketing performance measurement is an assessment of the relationship between marketing activities and business performance (Sullivan & Abela, 2007). Performance indicators are used to track company performance through measurable characteristics and many researchers have commented on performance measurement from different perspectives. Performance indicators can be seen from two dimensions, namely financial criteria and operational criteria as well as alternative data sources (Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986). Financial performance includes sales revenue, sales growth, value added share, marketing productivity (sales divided by marketing expenditure), return on sales and return on investment, and earnings per share. However, the broader operational performance (ie non-financial) includes market share, product quality, new product introduction, marketing effectiveness, manufacturing value added and other technological efficiency measures. The second dimension reflects the sources of performance data and can be classified as primary, where data is collected directly from the organization or secondary, where data is collected from publicly available records (Kurniawan, Budiastuti, Hamsal, & Kosasih, 2021).

Based on the description above, the success of a company is measured by its ability to generate profits (Syam, Hess, & Yang, 2016). In other words, business success occurs if the company can get the maximum profit from the growing market share (Veenraj & Ashok, 2014). Thus, the increase in market share will increase sales, and increased sales will have a direct impact on sales performance. Therefore, product quality and service quality must get maximum attention from the company so as to produce maximum profits (Li, Zhu, & Park, 2018).

Hypotheses and Research Model

Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on relational capability

Walter, Auer, & Ritter, (2006) argues that networking capability is the company’s ability to develop and utilize inter-organizational relationships in order to gain access to various resources owned by other actors. Networking capability is also described as the company’s ability to obtain resources from the environment through the creation of alliances and social ties to use in their activities in the marketplace. (Gulati, 1998;Solano Acosta, Herrero Crespo, & Collado Agudo, 2018). Therefore, networking capability is also understood as a dynamic capability that allows companies to identify opportunities and respond quickly. (Knight & Liesch, 2016;Solano Acosta et al., 2018).

Several authors have shown that networking capability is integrated by various dimensions representing different capabilities for managing relationships with other organizations and partners. Relational skills include certain aspects such as communication skills, extroversion, capacity to handle conflict, empathy, emotional stability, self-reflection, sense of justice and cooperation (Marshall, Goebel, & Moncrief, 2003;Solano Acosta et al., 2018). Based on the information above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypotheses 1: Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on relational capability

Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility

Networking capabilities enable companies to acquire, create, share knowledge, and build partnerships with stakeholders including customers and partners to consolidate strategic partnerships. With this capability, companies can easily gain flexibility, make it easier to leverage critical resources, and find business partners who work across borders to achieve agility (Kurniawan et al., 2021). This agility includes strategic sensitivity, collective commitment and resource fluidity, which allows companies to understand early, decide quickly, and strike with power and speed (Vagnoni & Khoddami, 2016). In other words, strategic agility is a complex variable that needs to take into account different dimensions to capture: customer, operational (internal) and partnering agility (Sambamurthy, Bharadwaj, & Grover, 2003;Vagnoni & Khoddami, 2016). With this situation, companies can seize better opportunities faster and face all potential competition and threats (Battistella, De Toni, De Zan, & Pessot, 2017;Liu & Yang, 2020).

Rezazadeh & Nobari, (2018) argued that to speed up the decision-making process, it can be done by building synergies with partners in the form of cooperation. With this collaboration, companies can leverage the resources and knowledge of partners to realize company agility (Kurniawan et al., 2021). Therefore, partnerships built with partners will be able to encourage companies to achieve the same level of ability, competence and flexibility in their companies so that they are in line with customer demands and rapidly changing markets (Yusuf et al., 2014). Based on the explanation of the relationship between networking capability and business process agility, business process agility, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 2: Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility

Relational capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility

The relational capability approach is a concept that discusses inter-organizational management (Pagano, 2009) where this concept describes the strategy of alliance partners to modify organizational routines to achieve effective integration and higher partner performance (Pagano, 2009). They are mostly embedded in organizational routines, which are repetitive activities that companies develop to deploy resources such as network relationships more effectively (Heimeriks & Duysters, 2007;Golgeci & Gligor, 2017). The relational view holds that valuable resources are embedded in the partnership rather than in the company itself Generally, companies in partnership need routines to facilitate knowledge sharing and source new ideas from strategic partners. These routines help companies to process information at a faster rate, and they build the foundation for strong coordination and for the co-generation of new ideas in strategic collaboration (Dyer & Singh, 1998;Pagano, 2009). Thus, the partnership will benefit from between partners so that the weaknesses of one partner match the strengths of the other partners, and vice versa. To realize these synergies, however, companies need complementary capabilities, which refers to the ability to identify and evaluate potential complementarities in other companies to find out how to utilize these strategic resources (Kale;, 2007). These complementary capabilities enable companies to identify potential synergies, to pool and exchange resources and capabilities with partners, and consequently to create value that a single company cannot achieve. (Pagano, 2009). Based on the explanation of the relationship between relational capability and business process agility, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 3: Relational capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility

Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance

Interact with diverse network participants, such as competitors (Rothaermel & Deeds, 2006), supplier (Sako, 2004), and customers (Dyer & Singh, 1998) can help companies manage diversity of information (Koka1 & Prescott, 2008) from external sources to create new and valuable combinations of technologies (Espinosa & Soriano, 2017). This interaction can increase the market potential and financial value of the company (Ciravegna, Majano, & Zhan, 2014;Kim & Lui, 2015).

Interaction with different types of external actors will facilitate the discovery of new opportunities (Shipilov, 2006) and enables companies to use a variety of instrumental, normative, and procedural information. Therefore, network diversity is very important for companies that lack internal resources and routines to acquire and exploit disparate information. In addition, the diversity of network partners further enhances the company’s ability to increase flexibility. Based on the explanation of the relationship between networking capability and company performance, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypotheses 4: Networking capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance

Relational capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance

Most studies suggest that companies with high relational abilities will earn higher profits (Smirnova et al., 2011) . Rodríguez-Díaz & Espino-Rodríguez, (2006) argues that certain competitive advantages are created through interactions with business partners and can only be achieved and sustained if firms develop the dynamic capabilities to be able to continue those business relationships. in the face of environmental change. As well as, Dyer & Singh, (1998) shows that relational advantages are created through the development of relational abilities, and Jacob, (2006) regard market success as a direct result of a company’s ability to integrate customer interactions into its organizational routine.

Therefore, those companies that have created relational capabilities within the organization aimed at better customer integration and coordination of inter-company relationships, will also have superior business results. (Smirnova et al., 2011). Based on the explanation of the relationship between relational capability and company performance, we formulate the following hypothesis.

Hypotheses 5: Relational capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance

Business process agility has a positive and significant impact on marketing performance

Business process agility will have a positive impact on the organization, where the organization can respond to dynamics in the market easily and quickly (Van Oosterhout et al., 2006). With this view, business process agility is often considered as one of the main contributors to achieving superior organizational performance. (Sambamurthy et al., 2003). Therefore, strong business process agility enables organizations to customize products or services to suit their customers. (Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011).

Several research results suggest that there is a positive and significant relationship between business process agility and company performance. This finding was put forward by several researchers, including Tallon & Pinsonneault, (2011) found a positive relationship between business process agility and firm performance in the IT industry. The same was stated by Vickery, Droge, Setia, & Sambamurthy, (2010) who found a positive relationship between business process agility and firm performance in the manufacturing industry. Ai Ping, Kaih Yeang, & Rajendran,( 2017) found that strategic agility can positively mediate corporate risk management practices and firm performance. Kale et al., (2019) found that business process agility will mediate the relationship between absorptive capacity and firm performance. Based on the explanation of the relationship between business process agility and company performance, the following hypothesis is formulated.

Hypotheses 6: business process agility has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance

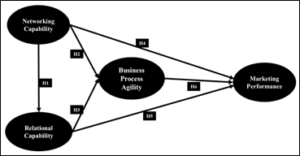

From the description above, the following is an empirical research model developed to complement this research.

Figure 1: Research Model.

Methodology

Sample and Respondent

Research data was obtained and collected through questionnaires distributed through several methods, including electronic forms and printed formats that were delivered directly to respondents. The assessment of the question questionnaire was carried out in a closed and open manner with a scale of 1 to 10 to a number of respondents according to the research criteria. The sampling technique was carried out purposively based on professional criteria at the level of company directors from selected companies who are believed to have good performance and have knowledge. quite good about the company’s strategy and business processes at a contractor company in the province of Central Java. The age of the respondent is at least 30 years, and has a minimum of 2 years of working experience in sales. Based on these criteria, there are 228 high management levels of the company selected as respondents according to predetermined criteria.

Measurement

The research variables used consisted of four variables: networking capability, relational capability, business process agility, and company performance. The variables are measured using indicators adopted from various literatures that have been used in previous studies. The networking capability variable is measured by three indicators, including: perfecting the partnership network relationship, getting help from our partners in an accurate way, getting help from our partners on right time (Dyer & Singh, 1998;Gulati, 1998;J. Mu & Di Benedetto, 2012).

The relational capability variable is measured by three indicators, including: having the competence to create products and services for individual problem solutions, having the competence to control individual problem solutions appropriately, having the competencies needed to implement solutions. to problems for our customers (Jacob, 2006).

The business process agility variable is measured by four indicators, including: adjusting products or services to suit customer desires, reacting quickly to new product or service launches by competitors, expanding the market to regional or new markets, adopting new technology to produce products or services that are better, (Tallon et al., 2007;Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011).

The marketing performance variable is measured by three indicators, including: achieve increased profit margins, achieve product and service quality improvement, achieve increased customer satisfaction (Lee, Kim, Seo, & Hight, 2015;Simon; & Department, 2015).

Analysis

Qualitative analysis was conducted to see the general demographic picture by looking at the answer index number and the relationship between variables which were then linked to the answers to open-ended questions. Quantitative analysis was carried out by testing validity, reliability, normality, and hypothesis testing using the IBM AMOS 22 program.

Respondents in this study were company directors. Of the 254 respondents, only 228 respondents whose results can be used with details of 151 male directors, and 77 female directors. The majority of respondents are aged 30-35 years and have a bachelor’s degree. The following is the demographic data of the number of respondents presented in Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Data analysis was carried out using Amos software version 22.0 in measuring the causal relationship and the size of the regression as well as the goodness of fit model and cutting the average value of the extracted variance suggested > 0.5.

Variable

Frequency

Percentage (%)

Gender

Male

151

66.2

Female

77

33.8

Age

30 – 35 Year

108

47.4

36 – 40 Year

78

34.2

41 – 45 Year

27

11.8

46 – 50 Year

10

4.4

˃50 Year

5

1.8

Education

Bachelor

150

65.8

Master

68

29.8

Doctor

10

4.4

Instrument testing in this study was conducted using validity and reliability tests. The validity of this study uses convergent validity by testing factor loading and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). (NC) (RC) (BPA) (MP)

Construct

Items

Standard estimate

Convergent validity-AVE

Construct Reability

Networking Capability

NC3 : perfecting the partnership network relationship

0.68

0.598

0.816

NC4 : getting help from our partners in an accurate way

0.85

NC5 : getting help from our partners on right time

0.78

Relational Capability

RC1 : having the competence to create products and services for individual problem solutions

0.77

0.653

0.839

RC3 : having the competence to control individual problem solutions appropriately

0.83

RC4 : having the competencies needed to implement solutions. to problems for our customers

0.79

Business Process Agility

BPA1 : adjusting products or services to suit customer desires

0.87

0.684

0.896

BPA2 : reacting quickly to new product or service launches by competitors

0.87

BPA3 : expanding the market to regional or new markets

0.83

BPA4 : adopting new technology to produce products or services that are better

0.73

Marketing Performance

MP2 : achieve increased profit margins

0.72

0.518

0.764

MP4 : achieve product and service quality improvement

0.71

MP5 : achieve increased customer satisfaction

0.73

The instrument requirements that are declared valid are realized if the loading factor and AVE score are above 0.5 illustrates that the variance extracted from the indicators is larger for the formation of the latent variable. Table 2 shows that all loading factors and AVE scores are above 0.5, which illustrates that all instruments have met the qualifications, so it can be concluded that the instruments built are valid. the value of construct reliability (cr) variable networking capability, relational capability, business process agility and marketing performance greater than 0.7 so it can be said that the indicators have good internal consistency. From the description above, it can be concluded that the indicators used as observed variables for the latent variables can be said to have been able to explain the latent variables they formed.

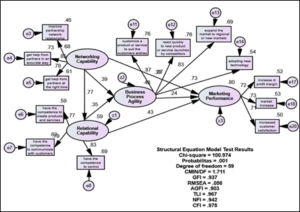

Goodness of Fit Testing

Before testing the model analysis model, the results are presented in Figure 1. Goodness of fit testing uses a statistical measurement of chi-square = 100.974 with a significance level of 0.089 or > 0.05 indicating the model is acceptable. Some non-statistical measurement indicators such as GFI = 0.937; AGFI = 0.903; TLI = 0.967; NFI = 0.942; CFI = 0.975 above the cut-off value 0.90 with RMSEA = 0.056 is below 0.08 so the model fits.

Figure 2: Empirical Research Model.

Hypothesized path regression coefficient H1 = 0.913; H2 = 0.420; H3 = 0.323; H4 = 0.267; H5 = 0.294; and H6 = 0.180 with a critical ratio or t-value > 2.0, precisely 1.96, indicating that all hypotheses in the model are acceptable (Table 3).

Hypothesized Path

Standardized Estimate

Critical Ratio

P-Value

Result

Networking Capital ® Relational Capital

0.913

9.835

***

Supported

Networking Capital ® Business Process Agility

0.420

3.220

0.001

Supported

Relational Capability ® Business Process Agility

0.323

2.953

0.003

Supported

Networking Capital ® Marketing Performance

0.267

2.830

0.005

Supported

Relational Capability ® Marketing Performance

0.294

3.616

***

Supported

Business Process Agility ® Marketing Performance

0.180

2.908

0.004

Supported

Hypothesis 1 states that networking capability has a positive and significant effect on relational capability. The results of the statistical test on hypothesis 1 show that the estimated parameter 0.913 describes a fairly decent variable and the CR value of 9.835 is above 1.96 and the probability of 0.001 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 1 can be accepted. This description of the results explains that there is a positive and significant relationship between networking capability which affects relational capability. The concept of networking capability for the context of the dynamics of the relationship and has a positive effect on the three stages of the relationship that enable the creation of dynamic portfolio management, namely initiation, development, and end, as well as focusing on network management activities in general. Therefore, networking capability as a dynamic capability is an organizational routine and practice that companies can develop to manage their supplier portfolio (Mitrega, Forkmann, Zaefarian, & Henneberg, 2017).

Hypothesis 2 states that networking capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility. Hypothesis 2 shows that the estimated parameter of 0.420 describes fairly feasible variable. In addition, the CR value of 3.220 is already above 1.96 and the probability of 0.001 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 2 can be accepted. This situation explains that the relationship between networking capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility . With this understanding, these capabilities allow companies to gain flexibility and leverage critical resources and business partners and work across boundaries to achieve agility. Thus, the company will be able to obtain reliable and fast information and competencies, which consequently makes the company strategically agile, so that it can capture better opportunities faster and face all potential competition and threats (Kurniawan et al., 2021).

Hypothesis 3 states that relational capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility. Hypothesis 3 shows the estimated parameter of 0.323 describing the variable as quite feasible. In addition, the CR value of 2.953 is already above 1.96 and the probability of 0.003 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 3 can be accepted. This situation explains that the relational capability has a positive and significant effect on business process agility . These results give an understanding that the success of the relationship is highly dependent on the quality of the relationship that is able to influence the success of the partnership, so that customers will benefit from good relationships, efficiency, supply chain agility, flexibility, and competitiveness. profit. Thus, the nature of the relationship between partners encourages interaction between partners (Rungsithong et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 4 states that networking capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. Hypothesis 4 shows the estimated parameter of 0.267 describing the variable as quite feasible. In addition, the CR value of 2,830 is already above 1.96 and the probability of 0.005 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 4 is acceptable. This situation explains that the networking capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. These results provide an understanding that companies with good networking capital will be able to increase profit margins, increase market share, and increase customer satisfaction (J. Mu et al., 2017).

The result of hypothesis test 5 states that salesperson value based selling has a positive and significant effect on sales performance. Hypothesis 5 shows that the estimated parameter 0.294 describes a fairly feasible variable. In addition, the CR value of 3.616 is already above 1.96 and the probability of 0.001 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 5 can be accepted. This situation explains that the relationship between relational capability has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. These results provide an understanding that salespeople with good relational capability will be able to increase the company’s profit margin, increase market share, and increase new customer satisfaction (Smirnova et al., 2011).

The results of hypothesis testing 6 state that business process agility has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. Hypothesis 6 shows that the parameter estimation of 0.180 describes a fairly feasible variable. In addition, the CR value of 2.908 is already above 1.96 and the probability of 0.004 is already below 0.05. These results conclude that hypothesis 5 can be accepted. This situation explains that the relationship between business process agility has a positive and significant effect on marketing performance. These results indicate that the more agile business processes carried out by the company will be able to increase the company’s profit margin, increase market share, and increase customer satisfaction.(Liu & Yang, 2020).

Discussion

In general, companies carry out networking activities aimed at obtaining competitive resources from outside the company. This activity is carried out because the company’s single relationship cannot provide all the resources needed by the company (De Leeuw et al., 2014). Therefore, efforts are needed to build a network between companies to gain momentum in strategic practice (Yang, Huang, Wang, & Feng, 2018) and to decide which network actions are important to them by examining the different outcomes of those actions (Mitrega, Ramos, Forkman, & Henneberg, 2012). For this reason, companies need to determine when the time is right to consolidate and stabilize relationships in order to strengthen existing network positions or create new positions by changing combinations of existing relationships or developing new ones. In other words, networking capabilities as a corporate competency are needed to find and find network partners, and manage and leverage network relationships for value creation (J. Mu & Di Benedetto, 2012).

Networking capabilities enable companies to acquire, create and share knowledge and build partnerships with key stakeholders. Network capabilities enable companies to obtain reliable and fast information and competencies, which makes the company strategically agile because it is well positioned at the core of its strategic network. (Kurniawan et al., 2021). By having this positioning, the company can seize better opportunities faster and face all potential competition and threats (Battistella et al., 2017; Kurniawan et al., 2021). Collaboration with partners allows companies to leverage partners’ resources and knowledge during joint project implementation, which is a valuable strategy for enterprise agility (Sanchez & Nagi, 2001;Kurniawan et al., 2021).

Business agility can motivate organizations to respond to dynamics in the market easily and quickly, so business agility can be used as one of the main contributors to achieving superior organizational performance. (Sambamurthy et al., 2003) and enables organizations to customize products or services to suit their customers (Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011) Organizational agility is also considered an important business driver for the survival and prosperity of contemporary companies in a chaotic business environment (Barreto, 2010;Liu & Yang, 2020). This can be done by detecting unexpected changes and responding quickly by reconfiguring resources, capabilities and strategies, both efficiently and effectively. (Gunasekaran, 1999).

Conclusion

From the results of this study, there are several conclusions that can be drawn. This study suggests that network capability, if linked to relational capability, will be able to improve a company’s business process agility to meet market demand, which in turn will be able to improve company performance. By leveraging network relationships with various stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, distributors, and others, companies will be able to access information, improve capabilities, and take coordinated actions between functions and between partners to create superior customer value. This situation will certainly enable the company to easily and quickly respond to changes in customer demand, adjust products or services, adopt new technologies and increase time to market, thus improving business performance.

This study shows that network capability supported by relational capability can improve a company’s business process agility in responding to market dynamics which in turn can improve the company’s marketing performance. This situation is shown by the results of research showing that network capabilities have a positive impact on business process agility which has a positive impact on improving marketing performance. In addition, networking capabilities mediated by relational capability have a positive and significant impact on business process agility as well as a positive and significant impact on marketing performance.

This study provides a perspective for professionals such as company directors on how to take advantage of their networking capabilities, either by utilizing their relational capabilities or without utilizing their relational capabilities to improve a company’s business agility, so as to improve the company’s marketing performance. Therefore, company directors and professionals can develop their network capabilities by adapting to customer business processes; leveraging the seamless network of teams to integrate process flows from customer intent or interest to buy products, to realization of company revenue based on product sales. In addition, directors and other company professionals need to direct organizational activities to create and satisfy customers through continuous needs assessment.

Based on the results of statistical tests on the developed model, it is recommended for further research that research be carried out with a wider scope involving other industries, which are not limited to contracting companies, but includes all directors in all existing industries so that the research results can be used by all directors in charge of other industries. Likewise, the sampling area also needs to be expanded, not only to cover the provinces of Central Java and Yogyakarta province, but also to cover all provinces in Indonesia. The aim is that the research results can be used by directors throughout Indonesia, with or without the need to make modifications in their implementation.

References

- Ai Ping T, Kaih Yeang L, Rajendran M (2017). The Impact of Enterprise Risk Management, Strategic Agility, and Quality of Internal Audit Function on Firm Performance. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7:222-229.

- Albekov A, Romanova T, Vovchenko N, Epifanova T (2017). Study of factors which facilitate increase of effectiveness of university education. International Journal of Educational Management, 31:12-20.

- Alrubaiee L S, Aladwan S, Abu Joma M H, Idris W M, Khater S (2017). Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Performance: The Mediating Effect of Customer Value and Corporate Image. International Business Research, 10(2), 104.

- Anderson J C, Hakansson H, Johanson J (1994). Dyadic Business Relationships within a Business Network Context. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 1.

- Avci U, Madanoglu M, Okumus F (2011). Strategic orientation and performance of tourism firms: Evidence from a developing country. Tourism Management, 32:147-157.

- Barreto I (2010). Dynamic Capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. Journal of Management, 36:256-280.

- Battistella C, De Toni A F, De Zan G, Pessot E (2017). Cultivating business model agility through focused capabilities: A multiple case study. Journal of Business Research, 73:65-82.

- Chen Y, Wang Y, Nevo S, Jin J, Wang L, et al. (2014). IT capability and organizational performance: The roles of business process agility and environmental factors. European Journal of Information Systems, 23:326-342.

- Ciravegna L, Majano S B, Zhan G (2014). The inception of internationalization of small and medium enterprises: The role of activeness and networks. Journal of Business Research, 67:1081-1089.

- Combe I A, Greenley G E (2004). Capabilities for strategic flexibility: a cognitive content framework. European Journal of Marketing, 38:1456-1480.

- Cook K S, Emerson R M, Gillmore M, Klepinger D, Mullendore A (2013). POWER, EQUITY AND COMMITMENT IN EXCHANGE NETWORKS. American Sociological Association, 43:721-739.

- De Leeuw T, Lokshin B, Duysters G (2014). Returns to alliance portfolio diversity: The relative effects of partner diversity on firm’s innovative performance and productivity. Journal of Business Research, 67:1839-1849.

- Dyer J H, Singh H (1998). The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660.

- Espinosa M del M B, Soriano D R (2017). Joint Ventures As An Alternative To Cooperation Learning. Department of Business Administration, 1-28.

- Gianni L, Andrea L (1999). The leveraging of interfirm relationships as a distinctive organizational capability: a longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 20:317-338.

- Golgeci I, Gligor D M (2017). The interplay between key marketing and supply chain management capabilities: the role of integrative mechanisms. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 32:472-483.

- Gorina, A. P. (2016). Issues and prospectives of the educational service market modernization. European Research Studies Journal, 19:227-238.

- Gulati R (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19:293-317.

- Gunasekaran A (1999). Agile manufacturing: a framework for research and development. International Journal of Production Economics, 62:87-105.

- Heimeriks K H, Duysters G (2007). Alliance capability as a mediator between experience and alliance performance: An empirical investigation into the alliance capability development process. Journal of Management Studies (Vol. 44).

- Heininger R (2012). Requirements for business process management systems supporting business process agility. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 284 CCIS, 168-180.

- Homburg, Müller, Klarmann (2010). When should the Custom er Really be king? The Institute for Market-Oriented Management.

- Jacob F (2006). Preparing industrial suppliers for customer integration. Industrial Marketing Management, 35:45-56.

- Jamil B M A B M (1998). Dynamics of Core Competencies in Leading Multinational Companies. CALIFORNIA MANAGEMENT REVIEW.

- Jaramillo F, Grisaffe D B (2009). Does customer orientation impact objective sales performance? Insights from a longitudinal model in direct selling. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29:167-178.

- KALE;, P. H. S. (2007). The Effect of Firm Compensation Structures on the Mobility and Entrepreneurship of Extreme Performers. Strategic Management Journal, 920(October), 1-43.

- Kale, E., Aknar, A., & Başar, Ö. (2019). Absorptive capacity and firm performance: The mediating role of strategic agility. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 78(January 2018), 276-283.

- Keszey T, Biemans W (2017). Trust in marketing’s use of information from sales: the moderating role of power. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 32:258-273.

- Kim Y, Lui S S (2015). The impacts of external network and business group on innovation: Do the types of innovation matter? Journal of Business Research, 68:1964-1973.

- Knight G A, Liesch P W (2016). Internationalization: From incremental to born global. Journal of World Business, 51:93-102.

- Koka1, b. R., & prescott, and j. E. (2008). Designing alliance networks: the influence of network position, environmental change, and strategy on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 920(October), 1-43.

- Kurniawan, R., Budiastuti, D., Hamsal, M., & Kosasih, W. (2021). Networking capability and firm performance: the mediating role of market orientation and business process agility. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 36:1646-1664.

- Lambe C J, Spekman R E, Hunt S D (2002). Alliance competence, resources, and alliance success: Conceptualization, measurement, and initial test. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30:141-158.

- Lebas, M. J. (1995). production economics Performance measurement and performance management “. Innovation, 41:23-35.

- Lee, Y. K., Kim, S. H., Seo, M. K., & Hight, S. K. (2015). Market orientation and business performance: Evidence from franchising industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44:28-37.

- Li, L., Zhu, Y., Park, C. (2018). Leader-member exchange, sales performance, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment affect turnover intention. Social Behavior and Personality, 46:1909-1922.

- Liu, H. M., & Yang, H. F. (2020). Network resource meets organizational agility: Creating an idiosyncratic competitive advantage for SMEs. Management Decision, 58:58-75.

- Luo, X., Hsu, M. K., Liu, S. S. (2008). The moderating role of institutional networking in the customer orientation-trust/commitment-performance causal chain in China. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36:202-214.

- Lussier, B., & Hartmann, N. N. (2017). How psychological resourcefulness increases salesperson’s sales performance and the satisfaction of their customers: Exploring the mediating role of customer-oriented behaviors. Industrial Marketing Management, 62:160-170.

- Marshall, G. W., Goebel, D. J., & Moncrief, W. C. (2003). Hiring for success at the buyer-seller interface. Journal of Business Research, 56:247-255.

- Mehra, A., Dixon, A. L., Brass, D. J., Robertson, B., Dixon, A. L., & Robertson, B. (2006). The Social Network Ties of Group Leaders : Implications for Group Performance and Leader Reputation The Social Network Ties of Group Leaders : Implications for Group Performance and Leader Reputation. Organization Science, (August 2014).

- Mitrega, M., Forkmann, S., Zaefarian, G., & Henneberg, S. C. (2017). Networking capability in supplier relationships and its impact on product innovation and firm performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 37:577-606.

- Mitrega, M., Ramos, C., Forkman, S., & Henneberg, S. C. (2012). Networking Capability, Networking outcomes, and Company Performance: A Nomological Model Including Moderation Effects. Industrial Marketing Management, 41:739-751.

- Morgan, N. A., Clark, B. H., & Gooner, R. (2002). Marketing productivity, marketing audits, and systems for marketing performance assessment: Integrating multiple perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 55:363-375.

- Mu J, Di Benedetto A (2012). Networking capability and new product development. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 59:4-19.

- Mu, J. F. (2014). Networking Capability, Network Structure, and New Product Development Performance. Ieee Transactions on Engineering Management, 61:599-609.

- Mu, J., Thomas, E., Peng, G., & Di Benedetto, A. (2017). Strategic orientation and new product development performance: The role of networking capability and networking ability. Industrial Marketing Management, 64:187-201.

- Pagano, A. (2009). The role of relational capabilities in the organization of international sourcing activities: A literature review. Industrial Marketing Management, 38:903-913.

- Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, D., & Evans, K. R. (2006). Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Relationship Marketing: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70:136-153.

- Paulraj A, Lado A A, Chen I J (2008). Inter-organizational communication as a relational competency: Antecedents and performance outcomes in collaborative buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Operations Management, 26:45-64.

- Payan J M, Hair J, Svensson G, Andersson S, Awuah G (2016). The Precursor Role of Cooperation, Coordination, and Relationship Assets in a Relationship Model. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 23:63-79.

- Raschke R L (2010). Process-based view of agility: The value contribution of IT and the effects on process outcomes. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 11:297-313.

- Raschke, R. L., David, J. S., David, J., Carey, W. P. (2005). Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Business Process Agility Recommended Citation Business Process Agility. Americas Conference.

- Rezazadeh A, Nobari N (2018). Antecedents and consequences of cooperative entrepreneurship: a conceptual model and empirical investigation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14:479-507.

- Ritter T, Gemünden H G (2003). Network competence: Its impact on innovation success and its antecedents. Journal of Business Research, 56:745-755.

- Rodríguez-Díaz M, Espino-Rodríguez T F (2006). Developing relational capabilities in hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18:25-40.

- Rothaermel, F. T., Deeds, D. L. (2006). Alliance type, alliance experience and alliance management capability in high-technology ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 21:429-460.

- Rungsithong, R., Meyer, K. E., & Roath, A. S. (2017). Relational capabilities in Thai buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 32:1228-1244.

- Sako, M. (2004). Supplier development at Honda, Nissan and Toyota: Comparative case studies of organizational capability enhancement. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13:281-308.

- Sambamurthy V, Bharadwaj A, Grover V (2003). Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of Information technology in Contemporary firms. Management Information Systems Research Center, 91:1689-1699.

- Sanchez, L. M., & Nagi, R. (2001). A review of agile manufacturing systems. International Journal of Production Research, 39:3561-3600.

- Seethamraju, R., & Krishna Sundar, D. (2006). Influence of ERP systems on business process agility. International Conference on Electronic Business (ICEB), 25:137-149.

- Shipilov A V (2006). Network strategies and performance of canadian investment banks. Academy of Management Journal, 49:590-604.

- Simon;, A. C. B. S. and B. S. E. K. S., Department. (2015). Business leaders’ views on the importance of strategic and dynamic capabilities for successful financial and non-financial business performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 53:177-196.

- Sivadas, E., & Dwyer, F. R. (2000). An examination of organizational factors influencing new product success in internal and alliance-based processes. Journal of Marketing, 64”31-49.

- Smirnova, M., Naudé, P., Henneberg, S. C., Mouzas, S., & Kouchtch, S. P. (2011). The impact of market orientation on the development of relational capabilities and performance outcomes: The case of Russian industrial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 40:44-53.

- Solano Acosta, A., Herrero Crespo, Á., Collado Agudo, J. (2018). Effect of market orientation, network capability and entrepreneurial orientation on international performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). International Business Review, 27:1128-1140.

- Srivastava, R. K., Fahey, L., & Christensen, H. K. (2001). The resource-based view and marketing: The role of market-based assets in gaining competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 27:777-802.

- Sullivan D O, Abela A V (2007). Marketing Performance Measurement Ability and Firm Performance. Journal of Marketing, 71(April), 79-93.

- Sultanova, A. V., & Chechina, O. S. (2016). Human capital as a key factor of economic growth in crisis. European Research Studies Journal, 19(2 Special Issue), 71-78.

- Syam N, Hess J D, Yang Y (2016). Can sales uncertainty increase firm profits? Journal of Marketing Research, 53:199-206.

- Tallon P P, Hall F, Ave C, College B, Hill C, et al. (2007). Inside the Adaptive Enterprise: An Information Technology Capabilities Perspective on Business Process Agility. Research on Information Technology and Organizations, (March).

- Tallon, P. P., & Pinsonneault, A. (2011). Echnology a Lignment and O Rganizational a Gility : I Nsights From a M Ediation M Odel 1. MIS Quaterly, 35:1-24.

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(March), 77-116.

- Terho, H., Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., Haas, A., & Böhm, E. (2017). Selling Value in Business Markets: Individual and Organizational Factors for Turning the Idea into Action. Industrial Marketing Management, 66:42-55.

- Toryanto, A. A., & Hasyim. (2017). Networking quality and trust in professional services. European Research Studies Journal, 20(3), 354-370.

- Vagnoni E, Khoddami S (2016). Designing competitivity activity model through the strategic agility approach in a turbulent environment. Foresight, 18:625-648.

- Van Oosterhout, M., Waarts, E., & Van Hillegersberg, J. (2006). Change factors requiring agility and implications for IT. European Journal of Information Systems, 15:132-145.

- Venkatraman N, Ramanujam V (1986). Measurement of Business Performance in Strategy Research: A Comparison of Approaches. Academy of Management Review, 11:801-814.

- Vesalainen, J., Hakala, H. (2014). Strategic capability architecture: The role of network capability. Industrial Marketing Management, 43:938-950.

- Vickery S K, Droge C, Setia P, Sambamurthy V (2010). Supply chain information technologies and organisational initiatives: Complementary versus independent effects on agility and firm performance. International Journal of Production Research, 48:7025-7042.

- Wachner Trent, Plouffe R. Christopher, G. Y. (2009). SOCO’s impact on individual sales performance: The integration of selling skills as a missing link. Industrial Marketing Management, 38:32-44.

- Walter, A., Auer, M., Ritter, T. (2006). The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 21:541-567.

- Yan Y, Zhang S H, Zeng F (2010). The exploitation of an international firm’s relational capabilities: An empirical study. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18:473-487.

- Yang, Z., Huang, Z., Wang, F., & Feng, C. (2018). The double-edged sword of networking: Complementary and substitutive effects of networking capability in China. Industrial Marketing Management, (January).

- Yusuf, Y. Y., Gunasekaran, A., Musa, A., Dauda, M., El-Berishy, N. M., & Cang, S. (2014). A relational study of supply chain agility, competitiveness and business performance in the oil and gas industry. International Journal of Production Economics, 147(PART B), 531-543.