Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Textualizing Memory of the Landscape in Tibet: The Pilgrimage Tradition of Mount Drakar Dreldzong

ཡུལ་མཐོ་ས་གཚང་(གཙང)བོད་ཀྱི་ཡུལ། གངས་རི་མཐོ་གཚང་(གཙང)ཀུན་ཀྱི(གྱི)གཉའ།

ཆུ་བོ་ཀླུང་ཡས་ཀུན་ཀྱི་(གྱི)མགོ ། ལྷ་གཉན་ཡུལ་དབྱིངས་དཀྱིལ་འདི་ན།

–ཏུན་ཧོང་ཡིག་ཆ P.T.1290ལས་བྱུང་བའི་བསྟོད་གླུ་ཞིག (དུས་རབས8-10བར)

Tibet is high and its land is pure.

Its snowy mountains are at the head of everything,

The sources of innumerable rivers and streams.

It is the centre of the sphere of the gods.

– An old Eulogistic song in Dunhuang manuscript

P.T.1290 (8th-10th century)

Tseten Gyal Lhade (CAI DANJIA)

Qinghai Minzu University, Xining, China

Received Date: November 30, 2024; Accepted Date: December 04, 2024; Published Date: December 12, 2024;

*Corresponding author: Tseten Gyal Lhade (CAI DANJIA), Qinghai Minzu University, No. 3, Bayi Middle Road, Xining, Qinghai Province, China, 810007. Email:tsebrtnrgyl@163.com

Abstract

This article explores Mount Drakar Dreldzong, a sacred site in Amdo, Tibet, through gnas yigs like The Guide and The Praise. These texts reveal the transformation of local deities and landscapes into Buddhist symbols, exemplifying Buddhisization and the interplay between memory, landscape, and religious tradition. While integrating indigenous beliefs into Buddhist frameworks, these texts selectively preserve and reshape cultural memory, balancing oral traditions with written narratives. Drakar Dreldzong’s evolution into a triune sacred site—Avalokiteśvara’s land, the second Tsari, and the Chakrasamvara Mandala—reflects broader trends in Tibetan sacred geography. The study highlights gnas yigs as essential tools for cultural adaptation and memory, offering insights into Tibetan interactions with sacred landscapes amid shifting historical and ecological contexts.

Keywords: Tibetan Sacred Geography, Buddhist Mountain Pilgrimage, History of Drakar Dreldzong, Cultural Memory, gnas yigs.

Introduction

The towering mountains and azure lakes of the Tibetan Plateau, as distinctive natural features, are regarded by Tibetans as sacred in various ways, with many surrounding mountains holding a special status in their social and cultural lives. Through thousands years of cultural practice within various cosmographic ideologies of the Tibetan tradition, the natural landscape has been conceptualized as a realm of sacred existence. Research has shown that interrelated notions of the mountain, encompassing indigenous cultural practices, pagan beliefs, and religious ceremonies, have contributed to the formation of a unique belief system. In the context of today’s environmentally challenging world, the traditional thoughts and practices of Tibetan people regarding their interactions with the environment can be regarded as crucial contributors, providing valuable insights for addressing and rethinking environmental problems on the Plateau while complementing modern scientific methodologies. The knowledge of recognizing landscapes as prominent and numinous in Tibet could date back to prehistory and continues to persist in modern times, though weakening in many ways.

In the early Tibetan conception of space, each mountain is paired with a nearby lake, a framework referred to as the Divine Dyads, as proposed by John Vincent Bellezza (Bellezza 1997, 1-15). While the male aspect is embodied by the mountain (yab, the father), the lake is recognized as its female counterpart (yum, the mother). For example, the famous Mount Kailash and Ma Pham Lake (ma pham gyu mtsho) in the Ngari region, as well as Gnyanchen Thanglha (gnyan chen thang lha) and Gnam Tsho (gnam mtsho) in Northern Tibet, are each presented as male and female combinations. Nevertheless, on some occasions, the male and female aspects are represented by two mountains. This sacred geographical union is a common feature across nearly every part of Tibet.

Later, with the introduction of Buddhist pilgrimage in Tibet, the concept evolved into something what we call “the Divine Triad” form of union, where two major mountains and a lake unified into one sacred geographical entity, known as the mountain-lake-sacred site pair (gang mtsho gnas gsum). In Western Tibet, the Divine Triad refers to Mount Kailash, Ma Pham Lake, and sPos Ri Ngad Ldan (spos ri ngad ldan). In Eastern Tibet, specifically in the Amdo region, it includes A-myes rma-chen (A’ myes rma chen), Kokonor Lake (mtsho sngon po), and Mount Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong), which will serve as the primary focus of discussion in this article. Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong) [i], esteemed as one of Amdo’s most sacred mountains, has endured through the ages as a profound cultural symbol, reflected in both religious scriptures and oral traditions of the region—sometimes through divergent, yet at other times, complementary narratives. In this article, I will focus on the cultural formation of Mount Drakar Dreldzong as a case study, using a set of textual representations in the past to explore the following questions: What are the basic and fundamental principles of mountain culture in Tibet? How do different texts represent the pilgrimage to Drakar Dreldzong? How has the memory of the Drakar Dreldzong pilgrimage evolved over time, and in what ways has it changed?

In various respects, these two forms of textual narratives trace the origins, transitions, and transformations of the sacred mountain’s cultural significance. The Pilgrimage Guide to Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong gi dkar chag, hereafter The Guide) and the Praise of the Melodious Sound of the Right-Turning Dharma Conch for Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong gi bstod pa chos dung g.yas su ‘khyil ba’i sgra dbyangs, hereafter The Praise) are two foundational Buddhist works that articulate the religious sacredness of Drakar Dreldzong. Here, I will refer to these texts by the Tibetan term “gnas yigs”, a term that can be considered equivalent to what Katia Buffetrille has proposed as “pilgrimage texts” [ii] (Buffetrille 1997, 89-112).

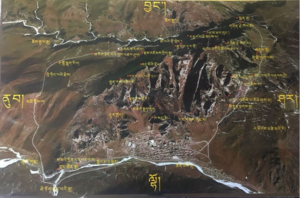

Picture 1: Mount Drakar Dreldzong and its pilgrimage route as seen through Google Earth.

Picture 2: Mount Drakar Dreldzong, winter of 2019, (Photo courtesy of the author)

The Media of Memory: Writing Traditions of Drakar Dreldzong

Situated at a crucial transportation crossroads leading to Central Tibet (dbus gtsang), Drakar Dreldzong has historically served as a prominent center of religious pilgrimage and intellectual activity, attracting eminent figures from various traditions who produced significant literary works during their sojourns. The extant corpus of texts related to Drakar Dreldzong is primarily composed of pilgrimage guides (gnas yig) [iii] authored by eminent lamas representing various religious lineages. Among these, The Guide, likely attributed to the 6th Karmapa, Choekyi Wangchuk, and subsequently compiled by Drigung Cheeji Drakba, stands out as a significant work,[iv] alongside Hymns of Praise, composed by the renowned Nyingma yogi Zhabs dkar Tshogs drug Rang grol (1781–1850); The Melodious Praise of Dreldzong, authored by Arol Lobsang Lungrtogs Tenpai Gyaltsen (1888–1958); The Praise, composed by Dobi Geshe Sherab Gyatso (1884–1968); and The Jewel Garland of Melodious Sound: A Pilgrimage Guide to the Great Sacred Site of Drakar Dreldzong, by the contemporary scholar Rongwo Lhagyal Pal. Originating from various historical periods and religious traditions, these texts provide a multifaceted array of perspectives on the development of Drakar Dreldzong‘s sacred pilgrimage culture. They illuminate the ways in which religious figures have actively contributed to shaping the evolving significance of this sacred site.

In the Tibetan pilgrimage study field, much of the scholarly literature refrains from proposing overarching theories. Instead, when theoretical frameworks are employed, they are frequently used to highlight their limitations in effectively addressing the distinct aspects of Tibetan pilgrimage (Hartmann 2024, 3). To address this gap, I will apply Jan Assmann’s theory of cultural memory to the study of Tibetan pilgrimage. The theory of cultural memory, proposed by German scholars Jan and Aleida Assmann in the late 20th century, expands upon Maurice Halbwachs’ “social framework theory” or “collective memory” (Halbwachs, 1950). The Assmanns seek to explain how memory develops in relation to the expansion and transmission of civilization. They emphasize the cultural aspect of memory, asserting that it is sustained through structured, collective, and public forms of communication. Additionally, they categorize its modes of transmission into two distinct forms: rituals and texts (Assmann 2005, 122-139). German Tibetologist Peter Schwieger was the first to incorporate this theoretical approach into Tibetan studies, arguing that, in addition to collective memory, the natural landscape plays a fundamental role in shaping Tibetan civilization.(Schwieger 2013, 64-85). Traditional pilgrimage guides often reflect an immersive interaction with sacred mountain landscapes, prominently illustrating the construction of collective memory. (Buffetrille 1998, 18-34 ).

The creation of these gnas yigs of Drakar Dreldzong represents a pivotal step in the textualization of cultural memory, serving as tools that encapsulate the collective imagination in written form. Unlike oral histories, these texts granted Tibetan scholarly elites access to Jan Assmann’s concept of “core texts” (Assmann 2011, 28–31 ) within sacred landscape culture, enabling them to shape how memory was documented and conveyed. Organized with detailed accounts of the mountain’s landscape and sacred sites, these texts often open with mythological narratives, entwined with local historical events and figures drawn from shared memory.

Field works I conducted at Drakar Dreldzong suggest that by the early 20th century, Dreldzong Monastery, which was constructed much later at the base of the Mount Drakar Dreldzong, had gradually supplanted the mountain as the primary focus of pilgrimage activities.[v] In my view, the framework discussed by Jan Assmann (Assmann 2011, 70–150, 191–205) on transitions in cultural memory can, to some extent, be applied to analyze how Buddhist pilgrimage transitions from peripheral to central memory. As a result, in contemporary practice, the pilgrimage predominantly focuses on the monastery, with the mountain’s circumambulation serving as just one component of the ritual. Despite this shift, the sacred mountain endures as a latent cultural memory, preserved within texts and rituals. [vi]

The Guide primarily narrates the myth of Padmasambhava’s[vii] triumph over demons, his subjugation of the local mountain deity Great Moon Nyan Monkey (gnan spren zla ba chen po), and the transformation of the mountain landscape into a sacred Buddhist site. The Tibetan term “Nyan” here is a very old notion, commonly alludes the numina that occupy intermediate space in the vertical axis of the universe. The mountain functions as a geographical entity dividing the universe into tripartite realms: the lha (the gods or deities) in the sky, the gNyan (Mountain-dwelling spirits or worldly deities) in the middle and the klu (Water spirits or serpentine beings) in the underground-known as “the three lha klu gnyan” (lha klu gnyan gsum). Therefore, as Samten. G. karmay suggests, in this cosmographic structure, the gNyan is normally understood as being the local deity or territorial god (yul lha or gzhi bdag) as they are thought to dwell at the peaks, slopes and the foot of the mountains (Karmay 1998, 432-451). In this case, the Great Moon Nyan Monkey could be categorized as a yul lha gzhi bdag type of deity, strongly connected with the earlier Tibetan Mountain cult—a distinct unwritten tradition of the laity in which neither Buddhist nor Bonpo clergy play a significant role. Hence, we can easily assume that the subjugation of the Great Moon Nyan Monkey highlights the confrontation between indigenous culture (likely predating the Bon as a religious tradition[viii]) and the expanding influence of Buddhism in Tibet. This aligns with what Katia Buffetrille termed the ‘Buddhisization’ of the Tibetan Plateau (Buffetrille 1998, 33-47). She examines how Buddhist practices and ideologies have been integrated into the certain region’s indigenous traditions of Tibetan Plateau, leading to a unique synthesis of religious expressions. This integration has significantly influenced the cultural and spiritual landscape of Tibet, reshaping local customs and the significance of sacred sites.

The Guide begins with a mythological account of the sacred site’s origin. The story is as follows:

“Padmasambhava pursued seven demon spirits from Lake Kokonor (approximately 210 kilometers northeast of Mount Dreldzong) to Mount Dreldzong. While meditating in a cave on the mountain, the demons sealed the entrance with a massive boulder. In response, Padmasambhava used his vajra to pierce through the rock and flew out of the cave, subsequently subduing the seven demons with his magic powers. During his retreat in the Vajra Loka Palace (Dorje Lokar Phodrang) on Mount Dreldzong, he encountered the mountain deity with the body of a human and the head of a monkey[ix], who claimed to be the guardian of the sacred mountain. Padmasambhava subdued this guardian, initiated it into protector vows, and conferred upon it the name Great Moon Nyan Monkey.”

Surprisingly, a similar description appears in the bKa’ thang sde lnga (The Five Chronicles), written by the 14th-century terton (treasure revealer) Orgyen Lingpa (1323–1360). It portrays the Nepalese woman Śākyadeva as being seduced by demons and continues with the following lines:

“To a human body with human form,

And a monkey’s head,

A name and title were given:

‘the Great Nyan Monkey Talpa (brdal pa).’” [x]

The name “Great Nyan Monkey” appears here with its meaning, phrasing, and context strikingly similar to what is found in The Guide. Textual evidence suggests that the later description most likely originates from the bKa’ thang sde lnga. Apart from the spelling difference between “Brdal ba” (spreading or to spread) and “Zla ba” (the moon), likely a deviation from the original name, the other elements of the stanza remain consistent with the text, further reinforcing its connection to the bKa’ thang sde lnga. Moreover, the depiction of the deity as a monkey, along with its descriptive imagery, appears to be directly derived from the bKa’ thang sde lnga. Upon closer examination, this resemblance gains importance as it parallels accounts found in Padmasambhava’s biographies. As Toni Huber suggests, many of Tibet’s sacred sites are intimately connected to Padmasambhava, reflecting his enduring religious legacy and influence (Huber 1999, 83, 29).

This alignment demonstrates how later sources resonate closely with earlier narratives, highlighting the consistent portrayal of his profound impact in Tibet.

The second part of The Guide provides a Buddhist interpretation of the natural features on Mount Dreldzong, including its caves, relics, springs, unusual rocks, and trees. Under Buddhist symbolism, the mountain’s color, caves, flora, rocks, soil, water, as well as handprints and footprints, are all endowed with religious sanctity. These sacred elements are arranged in relation to a central deity or sacred object, forming an interconnected Buddhist landscape. Through this process, the physical features of the sacred mountain are reinterpreted as sites of profound cultural and religious significance.

The Role of Narrative Tradition in the Constructing and Forgetting Memories

Memory as Forgetting

In the pre-Buddhist Tibet, mountains were generally regarded as totemic animals, genealogical deities, or ancestral spirits of clans, establishing strong ties with local communities. After Buddhism was introduced to Tibet, there was a concerted effort to assimilate and reconstruct ancient traditions to align them with Buddhist teachings. While the mountain cult maintained a continuous presence, encapsulating the Tibetan cultural perception of the landscape, territorial gods were deliberately transformed into gnas ris[i] (sacred mountains).

As the earliest Pilgrimage text to Mount Dreldzong, The Guide consistently reflects efforts to reconcile the inherent contradictions within the identity of the mountain deity.[ii] The origin myth introduces the Great Moon Nyan Monkey, who is subdued by Padmasambhava and subsequently transformed into a protector deity. The process of transforming indigenous territorial deities into Buddhist sacred mountains, as discussed earlier, aligns with what Katia Buffetrille terms ‘Buddhisization.’ This transformation involves converting a mountain deity, traditionally venerated by laypeople once or twice a year on the mountain’s slopes, into a Buddhist holy site where pilgrims engage in circumambulation. At the end of The Guide, this deity reappears in the text, having evolved into one with flowing hair Dharma Protector (Zhang skyong Ral-ba-can) and a member of the Shambhala Vajradhara pantheon, perfectly transitioned from a fearsome local spirit to a Buddhist guardian. The internal conflict within the narrative exemplifies the mountain deity’s dual identity and twofold nature. On one hand, it becomes a compassionate protector of the Dharma, a renunciant follower of Buddhism, embodying the Buddhist worldview. On the other hand, it remains a worldly local deity, concerned with fame and fortune, reflecting a strong secular and folk tradition.

The transformation from mountain god to protector deity is not merely a change in nomenclature; it also entails a reconfiguration of status and function in response to a new cultural memory framework. This gradual process involves the evolution of the mountain’s identity from that of a territorial mountain god (yul lha) to a gnas ri, or the residence of the territorial god. In traditional cultural memory, the Great Moon Nyan Monkey, a deity symbolizing the entirety of the mountain, was reimagined as just one among many mountain deities following his conversion to Buddhism. His spatial domain, once encompassing the entire mountain, was reduced to a smaller, specific area. Consequently, his role diminished from that of a principal deity to a subordinate figure, with a corresponding erosion of his functional authority. This process is emblematic of the Tibetan practice of Opening the Sacred Gate (gnas sgo phye ba)[iii], signifying the reconstruction and reinterpretation of the mountain as a Buddhicized landscape. In this context, the original symbolic memory is diluted, rewritten, and, in some cases, forgotten or excluded from the canon of textual memory.

In this context, the landscape has been reorganized, rewritten, reshaped, and transformed into a Mandala according to Buddhist philosophy, with deliberate transformations still evident in certain areas. Consequently, under the process of Buddhicization, natural elements such as caves, animals, plants, rocks, soil, water, and even physical imprints like fingerprints and footprints on the mountain are believed to possess the power of blessings (byin rlabs). Therefore, any harm or destruction inflicted upon the mountain or its creatures, vegetation, and physical entities is considered an accumulation of negative karma (las ngan pa bsags pa’i rgyu), leading to adverse consequences.

Picture 3: A Thangka Painting of the Great Moon Nyan Monkey at Drakar Dreldzong Monastery (photo courtesy of the author, 2021)

Texts and Myths: Selective Forgetting in Cultural Memory

As stated earlier, the Tibetan Mountain cult originated as an unwritten tradition among the laity. The gods and spirits residing in places such as mountains and lakes played significant roles in local human affairs. The Great Moon Nyan Monkey, revered as the pre-Buddhist mountain deity of Drakar Dreldzong, embodies diverse layers of cultural memory that are preserved in local traditions. In my research, I discovered that while these older memories related to the mountain deity Great Moon Nyan Monkey tend to fade within written texts, they persist vividly and clearly in oral traditions, passed down through proverbs, songs, and folktales. Compared to textual records, these oral traditions appear more vivid and distinct. They are often connected to certain folk rituals, preserving past figures and events in memory, which are reenacted year after year during these ceremonies. One of the most famous examples of this is the volatile romance between the Great Moon Nyan Monkey and the Red-Faced Queen (tsunmo dmaryag ma). A popular vernacular lore is as follows:

“The Red-Faced Queen was originally the wife of the Great Moon Nyan Monkey, the territorial deity of Mount Drakar Dreldzong. She was renowned for her extraordinary beauty. One day, she caught the attention of a distant mountain god, Amnye Bayan. Captivated by Bayan’s honeyed words, the queen decided to elope with him. However, along the way, the Great Moon Nyan Monkey caught up with them. Furious, he unsheathed his long sword and struck the queen’s right temple. Fearing for his life, Bayan fled. As punishment, the queen was doomed to live in solitude in the valley, with her right scalp cursed to never grow new hair again.”[iv]

In texts, the Red-Faced Queen is referred to as the Red-Chested Queen (Btsunmo Brangdmar ma). This represents a point where written tradition converges with living realities (or oral traditions). Although the names “Red-Faced” and “Red-Chested” differ slightly, they both refer to a same mountain deity that resides in a mountain located in the southeastern lower valley, approximately five kilometers from Mount Drakar Dreldzong. The themes of infidelity, elopement, and conflict in the story form an ancient core of Tibetan sacred mountain mythology, serving as cultural markers for local nomadic communities. Unlike the figure of Padmasambhava in written texts, who is primarily associated with spiritual and worldly teachings, this legend reflects a more community-centered perspective, characterized by strong anthropomorphic elements.

The interactions between the mountain deities that related to Drakar Dreldzong closely mirror the dynamics of human society, offering insight into how myths resonate with local lived experiences. In cultural memory, historical facts are transformed into remembered history, thereby becoming myth. As Jan Assmann states, “through memory, history becomes myth. In this way, history does not lose its truthfulness; on the contrary, it gains normative and enduring power, and in this sense, it becomes real” (Assmann 2011, 28–31, 70–150).

The objective historical events of the past, when interpreted from different angles by various narrators and influenced by personal subjective factors, shift the focus of how memory is conveyed. This myth has generated multiple versions over time. However, in written texts, aside from her role as the wife of the Great Moon Monkey, the multidimensional identity and vivid characterization of the Red-Faced Queen have largely disappeared. While myths tend to emphasize the remembrance of these deities, texts gravitate more towards forgetting—or, to be more precise, the extent of forgetting is greater in textual records. This phenomenon is especially evident in The Praise, where the presence of mountain deities is almost completely absent.

Narrative Traditions and the Construction of Recent Memory: “The Praise” and Others

Text as Memoryscape

The other comparatively recent Pilgrimage Guide text, The Praise, was composed in 1945 by the renowned Gelugpa Geshe Dobi Sherab Gyatso[v] (1884–1968) at the request of the Third Arol Tulku Lobsang Lungrtogs Tenpai Gyaltsen (1888-1958) [vi]. This work is regarded as a sophisticated and authoritative account of Mount Drakar Dreldzong. This work is regarded as a sophisticated and authoritative account of Mount Dreldzong, composed in the elegant nine-syllable verse structure of Tibetan literary tradition. In contrast to the narrative-focused Guide, The Praise emphasizes the glorification and veneration of the sacred site, characterized by ornate language and heavily influenced by traditional Poetics theory. Many pilgrimage guide authors from this period were Gelugpa monks, and Sherab Gyatso, drawing on a variety of other pilgrimage guides, composed his work by incorporating prophecies and traditional cultural theories such as Tibetan geomancy.[vii] Consequently, The Praise represents a mature form of Mount Dreldzong’s pilgrimage literature, marking the standardization and formalization of the genre.

Brag Dgonpa Konchok Tenpa Rabgye (1801–?), the author of mDo smad chos ’byung, emphasizes the “Second Zari” [viii] attribute of Drakar Dreldzong when referencing The Guide. However, the cited text itself does not explicitly mention this characteristic. This discrepancy highlights how interpretations or attributions by later scholars or commentators can diverge from the original textual content. The term “Pure Crystal Mountain” (dag pa shel ri) symbolizes Mount Zari, mentioned in The Guide as one of the sacred spots on Mount Drakar Dreldzong. However, the text does not emphasize its broader role as a representation of the entire mountain. This distinction underscores the nuanced ways in which sacred sites are contextualized, reflecting both localized spiritual significance and broader cultural interpretations. The idea of Drakar Dreldzong as the “Second Zari” likely represents a reinterpretation that arose after the creation of The Guide. Mount Zari, a sacred mountain deeply rooted in the central Tibet, seems to have been symbolically projected onto Drakar Dreldzong, which is located in eastern Tibet. This act of religious reinterpretation reflects a broader pattern of reimagining sacred geographies to enhance the spiritual significance of a site, aligning it with established traditions and centers of pilgrimage. In Tibetan Buddhist gnas yigs, Mount Zari is generally seen as the Mandala Palace of Vajradhara deity (dpal ’khor lo sdom pa), possessing a homomorphic relationship with the cosmic triad and Mount Meru’s symbolic space.

During his practice at the site, the renowned Nyingmapa practitioner Zhabs dkar Tshogs drug Rang grol (1781 – 1851)[ix], commonly known as Zhabs dkar pa, wrote a song emphasized the attributes of Drakar Dreldzong as “the Avalokiteshvara Sacred Site” (thugs rje chen po’i gnas)[x], which was blessed by Padmasambhava.

“Ema! The sacred mountain Drakar Dreldzong,

Beautiful like pure crystal peaks piled up,

Blessed by the emanation of the sovereign Pema (Padmasambhava),

The supreme solitary retreat.”[xi]

However, he did not reference its Zari attributes. Nevertheless, in The Praise, asserted that Drakar Dreldzong as “being indistinguishable from the glorious Sacred Mountain Zari”[xii] (dpal gyi tsa ri tra dang gnyis su med) by Sherab Gyatso. Thus, the idea of designating Drakar Dreldzong as “the second Mount Tsari” likely emerged after the creation of both The Guide and the conceptualization of the Avalokiteshvara Sacred Site. Furthermore, the latter may be directly connected to Zhabs dkar pa. Additionally, the gnas yigs of Drakar Dreldzong, primarily authored by Lamas from various traditions, frequently depict specific landscapes of the sacred mountain as sanctified by renowned masters of their respective lineages

The audiences of these texts collectively engage through reading, which not only captures the evolving representation of Drakar Dreldzong as a memoryscape across different periods but also underscores the competitive use of cultural memory as a group resource. Yet, from a broader perspective, these instances of rivalry and contention often progress toward collaboration and unity, centered on the shared valorization of Buddhicization. Taking The Praise as an example, while the text establishes the Gelugpa’s discourse framework, it does not exclude the perspectives of masters from other traditions regarding Drakar Dreldzong. Instead, it incorporates their viewpoints through a nuanced narrative structure. This approach not only promotes the broad acceptance of the gnas yigs but also contributes to shaping Drakar Dreldzong’s identity within the Gelug tradition.

Texts serve as reflections of a society’s underlying realities, and gnas yigs can be viewed as expressions and reenactments of Buddhicization, embodying a multifaceted form of cultural memory. The Praise signifies that the capacity of cultural memory has reached a certain limit where the text has become canonical. The original principles of acceptance and compliance have gradually expanded throughout the entire writing tradition and have become the core criteria in the process of textual transmission (Assmann 2011, 28–31 and 70–150 ). In The Praise, unlike The Guide, there is no longer a need to elaborate on forgotten aspects of old memories or justify new ones. The landscape has been entirely transformed into an idealized Mandala, and the mountain deity has been seamlessly incorporated into the concept of a gnas ri.

Memory of Cultural Heroes in Tibetan pilgrimage Written Tradition

In Tibetan tradition, spiritual teachers hold great prestige and status. Prominent figures like Padmasambhava, Milarepa (1052–1135), and Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) consistently feature throughout the modification of gnas yigs. Sacred sites acquire deep transcendent meaning through their association with these saints, as reflected in pilgrimage literature narratives. These accounts of esteemed teachers and lamas are infused with legendary features, enriched by religious and literary embellishments. They encourage a departure from conventional historical interpretations, presenting these figures as cultural heroes in Buddhist tradition—transcending the physical realm yet firmly rooted in cultural memory (Schwieger 2013, 64-85). These figures can be invoked, revived, and reimagined through the practices of a yogi, the rituals of a Eminent monk, or the pure visions of a Guru, thus perpetuating their influence. In the sacred site construction narratives associated with Drakar Dreldzong, cultural heroes (See Table 2) such as Padmasambhava, Drigung Kyobpa Jikten Gonpo (1143 – 1217), Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), and the female practitioner Machik Lapdron (1055-1149) are consistently active within the pilgrimage written tradition. Their deeds, handprints, and footprints are essential for culturally interpreting the landscape. While these cultural heroes may seem to transcend reality, they consistently permeate all every aspect of local daily life, underscoring the intricate relationship between cultural memory and the physical landscape.

Compared to The Guide, The Praise presents a significantly larger array of cultural heroes, comprising spiritual masters, accomplished practitioners, and revered high monks. Originating from diverse regions and Buddhist school backgrounds, these figures differ notably from the semi-historical figures previously discussed. Their well-documented interactions with the Drakar Dreldzong tradition and verifiable historical presence establish their status as authentic historical figures. Each has devoted themselves to promoting Buddhism through activities such as preaching the Dharma, founding monasteries, and initiating disciples, while upholding the literary traditions outlined in The Guide in their scholarly and religious works. From the perspective of ordinary pilgrims, these tangible, flesh-and-blood individuals resonate more deeply and are more comprehensible than abstract conglomerations of deities representing profound theological doctrines. Under this dynamic Buddhist discursive framework, Drakar Dreldzong has been continuously reorganized and transformed, ultimately emerging as a super-community Buddhist sanctuary.

Reshaping Mont Drakar Dreldzong as a Buddhist Mandala world

According to the theory of Buddhist sacred geography, Mount Drakar Dreldzong is regarded as somewhat the central axis of the Mandala world. As something like Toni Huber notes, it was the ordering principle of the Mandala that was most frequently projected onto and embodied within the specific topography of the newly categorized cult mountains (Huber 1999, 26, 83). It is said that the sacred geography of Mount Drakar Dreldzong, as described in written traditions, includes its sanctuaries of earth, rocks, woods, and other physical elements, whether naturally or artificially formed. All of these are always perceived as manifestations of some kinds of the extraordinary Rangbyons (self-manifestation), or an image or form that is believed to have appeared through the power of byinrlabs (blessings) within the sacred geography of the Great Chakrasamvara Mandala Palace (dpal ‘khor lo bde mchog gi pho brang) where all the supreme deities are assembled. In Buddhism, it is believed that numerous sacred sites have been blessed through the manifestations of both the Nirmanakaya and Sambhogakaya, as detailed in various tantric texts. Among these, the twenty-four principal gnass (sacred sites) are thought to have been consecrated by the Sambhogakaya aspect of Buddha Shakyamuni, particularly in association with the glorious Heruka. Drakar Dreldzong is acknowledged as one of these gnass, sanctified through the Sambhogakaya’s manifestation in a manner comparable to Tsari in southern Tibet. The worldly realm, including the twenty-four gnass and beyond, is said to lack existence as a unified whole. This perspective reflects a distinctive doctrinal insight, emphasizing the unique attributes of Buddhist teachings. The Container and Content (snod bcud) cosmology of Tibetan Buddhism, combined with conventional Tibetan understandings of the environment and its inhabitants, conceptualizes the landscape of Mount Drakar Dreldzong as a central Mandala, evoking the collective imagination of the three realms (kham gsum).

Picture 4: 14th Centuray Chakrasamvara Mandala Thangka painting

(https://www.himalayanart.org/items/77204)

The three sacred sites—the peak (ri rtse) as the seat of mind, the upper slopes (ri sked) as the seat of speech, and the lower reaches (ri’gab) as the seat of body—are understood to represent the three dimensions of enlightened manifestation within the sacred geography of Mount Drakar Dreldzong. Together, they embody the unity of the Buddha’s body, speech, and mind within the Mandala of the glorious Chakrasamvara. This symbolic alignment is further mirrored in the three great sacred sites of the Amdo region, collectively known as Gangtso Gnas Gsum: Amnye Machen as the body, Drakar Dreldzong as the mind, and Tsongonpo (Kokonor Lake) as the speech, each distinctly corresponding to specific aspects of the Buddhist teachings. It is said that in the above-mentioned Mandala, divided into three realms—upper, middle, and lower—the rim places of the wheel (’khor lo’i rtsibs yul) are adorned with twenty-four bindus (thig le nyer bzhis), which correspond to the twenty-four sacred gates (gnas sgo nyer bzhis). These places are categorized into the eight gnas of celestial practice (mka’ la spyo pa’i gnas brgyad), the eight gnass of earth practice (sa la spyo pa’i gnas brgyad), and the eight gnas of underground practice (sa ‘og na spyo pa’i gnas brgyad) (bstan ’dzin rgya mtsho 2009, 32–35).

- The eight gnass of celestial practice(mka’ la spyo pa’i gnas brgyad)

- The White Conch Dharma gnas (dung dkar chos kyi gnas)

- The Yangdzong Dumo gnas (yang rdzong ‘du mo’i gnas)

- The Great Compassion gnas (thugs rje chen po’i gnas)

- The Conqueror of Enemies, the Noble One gnas (dgra bcom ‘phags pa’i gnas)

- The Wrathful Fierce Vajra gnas (khro bo sme brtsegs gnas)

- The Eight Sugatas gnas (bde gshegs brgyad kyi gnas)

- The Assembly of Celestial Practices gnas (mkha’ spyod tshogs kyi gnas)

- The Auspicious Mountain gnas (bkra shis la yi gnas)

- The eight gnass of earth practice(sa la spyo pa’i gnas brgyad)

- The Great Elephant Waterfall gnas (glang chen kha ‘bab gnas)

- The Path of Liberation High Mountain gnas (thar lam mtho ris gnas)

- The Dark Red Meat Mountain gnas (sha sgya smug pa’i gnas)

- The Enlightened Attainment gnas (sangs rgyas ‘grub pa’i gnas)

- The Sacred Place of Indian Lineage gnas (rgya gar pha dam pa’i gnas)

- The Purification by Conquering All gnas (rnam ‘joms khrus kyi gnas)

- The Cleansing Cemetery gnas (dur khrod bsil ba’i gnas)

- The Treasure of the Earth Gods gnas (‘dzam lha gter gyi gnas)

- The eight gnass of underground practice(sa ‘og na spyo pa’i gnas brgyad)

- The Renowned Everywhere gnas (yongs su grags pa’i gnas)

- The Crystal Clarity gnas (dag pa shel gyi gnas)

- The Vajra Cave gnas (rdo rje phug pa’i gnas)

- The Brave Monkey Spirit gnas (spre’u sems dpa’i gnas)

- The Realm of Desire Fulfillment gnas (‘dod ‘jo ba yi gnas)

- The Uddiyana Mantra Water gnas (o rgyan sngags chu’i gnas)

- The Gratitude Repayment gnas (drin lan mjal ba’i gnas)

- The Yak Liberation Cave gnas (ya ma thar khung gnas)

Picture 5: The twenty-four sacred sites of Mount Drakar Dreldzong in Tibetan (Photo courtesy of bstan ’dzin rgya mtsho, 2009)

The sacred sites found within the upper, middle, and lower realms of the mountain (gnas ri’i steng ’og bar gsum) are understood to be gathering places of deities (yi dam lha tshogs), heroes (dpa’ bo), and dakini attendants (mkha’ ’gro’i ’khor). As depicted in the thangka paintings of the Chakrasamvara Mandala (’khor lo sdod pa’i bris thang, see Picture 4), these sites are symbolically represented, centering around the principal deity, Glorious Heruka (dpal heruka), who embodies the ultimate bliss in union with his consort. Encircling them, the bindu (thig le) at the Mandala’s periphery is portrayed as a harmonious convergence of enlightened qualities. From this perspective, the inherent truth of self-arisen awareness (rang byung gi bden pa) becomes manifest, recognized through some kind of meditative insight (rig gnas kyi rtog pa). Such understanding enables one to perceive this sacred landscape with the clarity of a contemplative’s vision, where it is both visible to the eye (mig gis mthong pa) and tangible to touch (lag pas reg pa). This luminous realm (dag snang gyi zhing khams) thus provides a foundational ground for spiritual realization (lCang skya rol pa’i rdo rje 2014), 83).

Thus, it is said that the sacred gates of these sites are inherently linked to practitioners of various types, who arrive in these regions following the traces of great beings of the past. These individuals come for to dwell in the secluded mountain sanctuaries, forest retreats, or by the sides of trees, among other spiritually conducive locations for retreat of esoteric practice.

In summary, the connection between the sacred mountain and its practitioners reflects a profound relationship. According to the Chakrasamvara system, the outer Mandala (phyi snod) serves as a source of blessings, while the sacred gates correspond to the transformative potential of the practitioner’s energy channels (rtsa), inner winds (rlung), and bindu (thig le). These elements align in harmony, allowing for the transmission of blessings (byin rlabs) to flow into the practitioner.

Therefore, it is believed that undertaking spiritual practice in these sites with sincere dedication leads to unparalleled blessings (byin rlabs mchog). This makes them uniquely powerful places for cultivating realization and attaining the ultimate goals of the Chakrasamvara path.

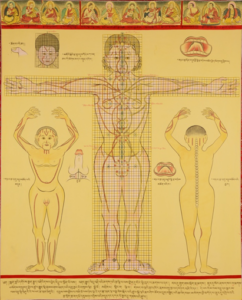

According to Tantric theory, if the practitioner correlates the twenty-four sacred gates (gnas sgo nyer bzhi) within the three regions—upper, middle, and lower (stod smad bar gsum)—with the composite elements of the human body (gang zag gi phung po), the principal channel (rtsa’i gtso bo), defined by the three vital points (rtsa gsum)—the central (dbu ma), right (ro ma), and left channels (rkyang ma)—serves as the foundational framework for these correlations. By aligning these channels and gates, one can enhance the power of blessings. The sacred channels flow from the dbu ma, subtly diffusing toward the back (sgal phyogs) near the spine, creating a continuum of expanding and refining energy. This flow then extends upward to the crown apex (yar sna gtsug gtor), radiating forward and focusing at the center of the forehead (smin dbus kyi thod pa). This continuum aligns with the energetic resonance of ro rkyang, symbolizing the “mouth” of the body opening to its intrinsic nature.

The principal path of the channels can be divided into three main regions, each containing numerous details. These regions correspond to different parts of the body (See Picture 5 and 6):

- In the upper section (stod), from the crown of the head (spyi gtsug) to the throat (phrag pa), there are eight sacred sites. These are associated with the celestial activities of the deities of the enlightened mind Mandala (thugs ‘khor lha tshogs), who dwell in space.

- In the middle section (bar), from the throat (mgrin pa) to the navel (‘bras bu), there are eight sacred sites. These correspond to the terrestrial activities of the deities of the speech Mandala (gsung ‘khor lha tshogs), who dwell on the earth.

- In the lower section (smad), from the palms of the hands (lag pa’i sor mo) to the soles of the feet (rkang pa’i sor mo), there are eight sacred sites. These align with the subterranean activities of the deities of the body Mandala (sku ‘khor lha tshogs), who dwell below the earth.

Picture 6: A Tibetan Medical Illustration of the Subtle Body, Depicting the Central Channel and Its Connection to Chakrasamvara Deities.[i]

(Photo Courtesy of the Author, 2021)

Thus, these twenty-four sacred sites correspond to the twenty-four root elements of the human body (lus kyi rtsa khams nyer bzhi). Through the power of mantra practices (sngags lugs), these elements are believed to pervade and activate the body. The sacred sites are venerated by heroes (dpa’ bo) and heroines (dpa’ mo) who are renowned for their steadfastness and diligence in assisting others and performing their respective activities in these sacred places.

In brief, the gnas yigs of Mount Drakar Dreldzong delve into the profound relationship between the act of circumambulation and the practitioner’s esoteric practices at the sacred landscape. They emphasize the necessity of balancing both internal and external aspects of practice, stating that without this harmony, progress cannot be achieved. These texts also reveal the transformative power of spiritual discipline, asserting that when body and mind are aligned in pure conduct, and the practitioner locates the right place, the practitioner’s path, thus, leads to the ultimate liberation and enlightenment.

Conclusion

The cultural and spiritual significance of Mount Drakar Dreldzong exemplifies the intricate interplay between memory, landscape, and religious tradition in Tibetan society. By analyzing gnas yigs such as The Guide and The Praise, this study has demonstrated how sacred geography is actively reshaped through textualization, myth-making, and ritual practice. These texts function as both preservers and reconceptualizers of cultural memory, transforming local deities and natural landscapes into symbols of Buddhist cosmology and moral narratives.

The process of Buddhisization (See Table 1) , as articulated by Katia Buffetrille, highlights the integration of indigenous beliefs into Buddhist practices, showcasing the adaptability of Tibetan cultural systems. Drakar Dreldzong’s transformation into a Mandala-like sacred structure reflects broader patterns in Tibetan sacred geography, where physical landscapes are reimagined as spaces for spiritual realization. However, this process also reveals the tensions between oral and written traditions, as the vivid anthropomorphic elements of pre-Buddhist lore often fade in written narratives, lingering more prominently in oral traditions and ritual practices. Through these evolving narratives, Drakar Dreldzong emerges as a dynamic cultural symbol, transitioning from its pre-Buddhist roots as a sacred mountain associated with the Great Moon Nyan Monkey to a triune Buddhist site representing the Avalokiteśvara land, the second Tsari, and later the Chakrasamvara Mandala. These transformations underscore the selective nature of cultural memory, where elements of history are consciously reshaped or forgotten to align with changing socio-cultural conditions.

As mediums of memory, gnas yigs strategically embellish, modify, and fictionalize the sacred mountain’s narratives, constructing a layered and evolving image that resonates with the collective Tibetan consciousness. The contributions of cultural heroes like Padmasambhava further solidify Drakar Dreldzong’s place within the Buddhist framework, as their symbolic acts of blessing, treasure revelation, and sanctification activate and perpetuate the mountain’s sacred identity. Ultimately, Mount Drakar Dreldzong in many ways serves as a microcosm of Tibetan cultural identity, reflecting the interconnection of the natural, spiritual, and human realms. By engaging with these texts, contemporary scholarship can uncover valuable insights into the preservation, adaptation, and transformation of cultural memory. This provides a crucial lens for understanding Tibetan interactions with their sacred landscapes in the face of historical, religious, and current ecological changes.

While one should always keep in mind that Assmann‘s cultural memory framework can offer insights into the studies of the sacred geography of Drakar Dreldzong, it is important to acknowledge its limitations when applied to Tibetan cultural practices. Rooted in Western intellectual traditions, Assmann’s theory emphasizes textual artifacts and institutionalized forms of memory. This perspective may not fully capture the richness of Tibetan practices, where memory and identity are deeply intertwined with spirituality and oral traditions rather than written records alone. In Tibetan culture, sacred landscapes, oral histories, and embodied rituals such as pilgrimage and prayer occupy a central role in the transmission of memory. These practices often blur distinctions that Assmann draws between short-term communicative memory (spanning up to three generations) and long-term cultural memory (institutionalized over centuries). Instead of being codified in texts, Tibetan memory often persists through dynamic, lived experiences that renew religious and material connections across generations. Moreover, Tibetan practices frequently integrate oral and material forms of memory transmission, as seen in the continuous spiritual activities surrounding sacred sites like Drakar Dreldzong. Assmann’s framework, with its emphasis on textualization, might inadequately address such non-textual forms. While these aspects are beyond the scope of this research, they highlight the need for broader frameworks that encompass diverse cultural memory practices.

Reference

- Arol Lobsang Lungrtogs Tenpai Gyaltsen.(2002). Collected Works of Arol Lobsang Lungrtogs Tenpai Gyaltsen. Qinghai Nationalities Publishing House, PP. 614–618.

- Assmann, Jan.(2006). Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Assmann, Jan.(2011). Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bellezza, John Vincent.(1997). The Divine Dyads: Ancient Civilization in Tibet. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives.

- Bellezza, John Vincent.(2005). Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains, and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet: Calling Down the Gods. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Buffetrille, Katia.(1997). “The Great Pilgrimage of A myes rMa-chen: Written Traditions, Living Realities.” In A. W. Macdonald (Ed.), Mandala and Landscape (PP. 75–132). Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

- Buffetrille, Katia.(1998). “Reflections on Pilgrimages to Sacred Mountains, Lakes, and Caves.” In A. McKay (Ed.), Pilgrimage in Tibet (PP. 18–34). England: Curzon Press Ltd. and IIAS.

- Halbwachs, Maurice.(1992). On Collective Memory (Lewis A. Coser, Ed. & Trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Originally published 1950).

- Hartmann, Christoph.(2024). “The Study of Pilgrimage in Tibetan Buddhism: Overview and Recommendations for Instructors.” Religion Compass, 18(9), e70003.

- Huber, Toni.(1999). The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karmay, Samten Gyaltsen.(1998). “The Cult of Mountain Deities and Its Political Significance.” In The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals, and Beliefs in Tibet (PP. 432–450). Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point.

- Karmay, Samten Gyaltsen.(1998). “Mountain Cult and National Identity in Tibet.” In The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals, and Beliefs in Tibet (PP. 423–431). Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point.

- lCang skya Rol pa’i rdo rje.(2014). “dPal dus kyi ’khor lo’i rtsa rlung thig le’i rnam gzhag mdor bsdus” and “Gsang sngags rdo rje theg pa’i sa lam gyi rnam gzhag.” In rGyud stod dpe mdzod khang (PP. 83).

- Punzi, Valentina.(2012). “Tense Geographies: The Shifting Role of Mountains in Amdo Between Religious Rituals and Socio-Political Function.” In IL TIBET FRA MITO E REALTA (Tibet Between Myth and Reality) (PP. 71–81). Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore.

- Ramble, Charles.(2014). “The Complexity of Tibetan Pilgrimage.” In Christoph Cueppers & Max Deeg (Eds.), Searching for the Dharma, Finding Salvation: Buddhist Pilgrimage in Time and Space (PP. 179–196). Bhairahawa: Lumbini International Research Institute.

- Schwieger, Peter.(2013). “History as Myth: On the Appropriation of the Past in Tibetan Culture.” In Gray Tuttle & Kurtis R. Schaeffer (Eds.), Tibetan History Reader. A Collection of Essays (PP. 64–85). New York: Columbia University Press.

- bstan ’dzin rgya mtsho, Dreldzong. (2009). “sprel rdzong gnas bshad lam stong gsal ba’i sgron me.” Dreldzong Monastery Management Committee (PP. 32–35).

- (2008). To Drakar Dreldzong: The Written Tradition and Contemporary Practices among Amdo Tibetans.Master’s Thesis, Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo.

- (2019). Pilgrimage Guide of the Tibetan Buddhist Holy Mountain Brag dkar sprel rdzong. In Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, PP. 179–183.

[i] In Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, the three channels of the human body—the central (rtsa dbu ma), right (rtsa ro ma), and left (rtsa rkyang ma)—are closely linked to the Chakrasamvara Mandala and the sacred space for meditation. The channels guide the flow of subtle winds (rlung), essential for inner transformation. The central channel aligns with the Mandala’s axis, representing unity and ultimate reality, while the right and left channels correspond to solar and lunar energies. The Chakrasamvara Mandala reflects the perfected universe and is visualized within the subtle body, integrating its geometry with the practitioner’s inner channels. Similarly, the meditation site mirrors the Mandala, harmonizing the external environment with the practitioner’s internal practice. This alignment of body, Mandala, and place facilitates the realization of the non-duality of mind and world, embodying the union of samsara and nirvana central to the Chakrasamvara tradition.

Appendix 1

Table 1: Comparison of the Landscape Buddhisization in The Guide and Praise.

| Gnas yigs | The Guide | The Praise | |

| Mandalas | 1. Four Tantric Mandalas (rgyud sde bzhi’i dkyil ‘khor)

2. Akanishta Dharmadhatu Palace (‘og min chos dbyings pho brang) 3. Eighty-petaled Tiger-Liberating Mandala (stag sgrol thig le brgyad cu’i dkyil ‘khor) 4. Blissful Pure Land’s arrangement (bde ba can gyi zhing bkod) 5. Eightfold Mandala of the Bodhisattvas surrounding Vairochana (bcom ldan rnam snang sems dpa’ brgyad ‘khor) 6. Pure Prasphotakah Celestial Palace Mandala (dag pa rab ‘byams gzhal yas khang) 7. Mandala of Eight Siddhas (sgrub pa bka’ brgyad dkyil ‘khor) 8. the Chakrasamvara Mandala (‘khor lo sdom pa’i dkyil ‘khor) 9. Four Tantric Mandalas

|

the Chakrasamvara Mandala (khor lo sdom pa’i dkyil ‘khor) | |

| Deities | 1. Naturally Appeared Guru Siddhi (gu ru sing dha rang byon)

2. Avalokiteshvara with Dharma Victors (spyan ras gzigs dang chos mchog) 3. Medicine Buddha (sangs rgyas sman bla) 4. Fierce Vajra Holder and Sixteen Guardians (drag po phur ba phur srung bcu drug) 5. Buddha Maitreya with eight closest disciples (rgyal ba byams pa nye ba’i sras brgyad) 6. Avalokiteshvara (spyan ras gzigs) 7. Male and Female Lord of Death (gshin rje pho gdong mo gdong) 8. Lord of Death (gshin rje chos rgyal) 9. The Dharma Protector with flowing hair (zhing skyong ral ba can) 10. The Red-Chested Queen (btsun mo brang dmar ma) 11. Sixteen Arhats (thub pa gnas brtan bcu drug) |

1. Avalokiteshvara (spyan ras gzigs)

2. Victorious Vajra Holder (dpal ldan rdo rje) 3. Twenty-four Dakinis (da ki na ni nyer bzhi) 4. King of Dharma (chos rgyal) 5. Arya Tara (arya tare ma)

|

|

| Masters | 1. Padmasambhava (u rgyan Padma ‘byung gnas)

2. Drikung Kyobpa Jigten Gonpo (‘bri gung skyob pa ‘jig rten mgon po) |

3. Padmasambhava (padma sambha wa)

4. Drikung Jigten sum Gon(‘bri gung ‘jig rten gsum mgon) 5. Labkyi Dronma (lab kyi sgron ma) 6. Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen (sa pan kun dga’ rgyal mtshan) 7. Je Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (‘jam mgon blo bzang grags pa 8. Shar Kelden Gyatso (skal ldan rgya mtsho) 9. Serkhangpa (gser khang pa) 10. Zhabs dkar tshogs drug rang grol (zhabs dkar ba tshogs drug rang grol) 11. Lobsang lungrigs Gyatso (Lobsang lung rigs rgya mtsho) 12. Lobsang Lungtog Tenpai Gyeltsen (blo bzang lung rtogs bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan) 13. The Great Leader Jir Degpon (‘jir dge dpon po) |

|

| Sacred Places | 1. The pure Shri Pristine Crystal Cave (dag pa shri shel gyi phug pa)

2. Bird Garuda (bya khyung ga ru ta) 3. Ugyen Miraculous Water (u rgyan sgrub chu) Master Padma’s Falling Abode (slob dpon padma ‘byung gnas lhung bzed) 4. Ugyen’s Sacred Throne (u rgyan bzhugs khri) 5. The Cow Bestowing Breast ( dod ‘jo ba yi nu ma) 6. Treasure Sacred gate (gnas sgo gter kha) 7. Intermediate Path of Liberation (bar do’i ‘phrang lam) 8. Bai Durya Alms Bowl ( be da rya’i lhung bzed) 9. Ninety-nine Stages of Liberation (thar ba’i them skas zhe dgu) 10. Sacred Footprints of Guru Padmasambhava (u rgyan padma’i zhabs rjes) 11. The Imprint of drum and other implements (phyag rnga sogs kyi rjes) 12. Path Steps of Liberation (thar lam them pa’i skas) 13. Six Nectar Types of Medicinal water (sman chu bdud rtsi ro drug ) 14. Chu Bzang White Mountain (chu bzang brag dkar) 15. Footprints of Machin Bomra mountain Deity (rma chen sbom ra’i zhabs rjes, spel mo brag) 16. Peak of Spelmo (spel mo brag)

|

1. Holy Water (grub chu)

2. Mountain Pass of Higher Realm (mtho ris la) 3. The Front Mountain Tara (mdun ri sgrol ma’i ri) 4. Right Mountain (g.yas ri) 5. Left Mountain (g.yon ri) 6. Pure Crystal Mountain (dag pa shel ri) 7. Chenmo Water(chen mo’i chu)

|

|

Table 2: The Role of Cultural Heroes in the Buddhisization Process of Drakar Dreldzong

| Cultural Heroes | Schools | Date of Birth and Death | Major Activities at Drakar Dreldzong |

| the 6th Redhat Karmapa, Choekyi Wangchuk | Kagyu | 1584-1630 | 1. ComposedThe Guide

2. Revealed Sacred Sites 1) Mandalas: Four Tantric Mandalas , Akanishta Dharmadhatu Palace (‘og min chos dbyings pho brang), Eighty-petaled Tiger-Liberating Mandala (stag sgrol thig le brgyad cu’i dkyil ‘khor), Mandala of Pure Crystal (bde ba can gyi zhing bkod), Eightfold Mandala of the Bodhisattvas surrounding Vairochana (bcom ldan rnam snang sems dpa’ brgyad ‘khor), Pure Prasphotakah Celestial Palace Mandala (dag pa rab ‘byams gzhal yas khang), Mandala of Eight Siddhas (sgrub pa bka’ brgyad dkyil ‘khor), the Chakrasamvara Mandala (‘khor lo sdom pa’i dkyil ‘khor), Four Tantric Mandalas. 2) Deities: Naturally Appeared Guru Siddhi (gu ru sing dha rang byon), Avalokiteshvara with Dharma Victors (spyan ras gzigs dang chos mchog), Medicine Buddha (sangs rgyas sman bla), Fierce Vajra Holder and Sixteen Guardians (drag po phur ba phur srung bcu drug), Buddha Maitreya with eight closest disciples (rgyal ba byams pa nye ba’i sras brgyad), Avalokiteshvara (spyan ras gzigs), Male and Female Lord of Death (gshin rje pho gdong mo gdong), Lord of Death (gshin rje chos rgyal), The Dharma Protector with flowing hair (zhing skyong ral ba can), The Red-Chested Queen (btsun mo brang dmar ma), Sixteen Arhats (thub pa gnas brtan bcu drug). 3) Masters: Padmasambhava (u rgyan Padma ‘byung gnas), Drikung Kyobpa Jigten Gonpo (‘bri gung skyob pa ‘jig rten mgon po). 4) Sacred Places: The pure Shri Pristine Crystal Cave (dag pa shri shel gyi phug pa), Bird Garuda (bya khyung ga ru ta), Ugyen Miraculous Water (u rgyan sgrub chu), Master Padma’s Falling Abode (slob dpon padma ‘byung gnas lhung bzed), Ugyen’s Sacred Throne (u rgyan bzhugs khri), The Cow Bestowing Breast ( dod ‘jo ba yi nu ma), Treasure Sacred gate (gnas sgo gter kha), Intermediate Path of Liberation (bar do’i ‘phrang lam), Bai Durya Alms Bowl ( be da rya’i lhung bzed), Ninety-nine Stages of Liberation (thar ba’i them skas zhe dgu), Sacred Footprints of Guru Padmasambhava (u rgyan padma’i zhabs rjes), The Imprint of drum and other implements (phyag rnga sogs kyi rjes), Path Steps of Liberation (thar lam them pa’i skas), Six Nectar Types of Medicinal water (sman chu bdud rtsi ro drug ), Chu Bzang White Mountain (chu bzang brag dkar), Footprints of Machin Bomra mountain Deity (rma chen sbom ra’i zhabs rjes, spel mo brag), Peak of Spelmo (spel mo brag). |

| A’mgron Khes Tsün Gya Tsho” (a mgron mkhas btsun rgya mtsho) | Ningmapa | 1604-1679 | In 1638, although it was made known that a Gnas yig was compiled here, it has been lost to history. |

| Zhabs dkar tshogs drug rang grol | Gelupa | 1781-1851 | 1. Recognized Drakar Dreldzong as the Avalokiteshvara Sacred Site.

2. Composed a series of praises and songs on Drakar Dreldzong. |

| Arol Lobsang lungrigs Gyatso | Gelupa | 1805–1888 | Discovered the sacred sites of Buddha Ruling Over the Klu (klu dbang rgyal po’i sku), Naturally Appeared Yogini (nal ‘byor ma rang byon), Tiger Garuda (stag khyung), Eleven-Faced Avalokiteshvara (spyan ras gzigs bcu gcig zhal),Avalokiteshvara with One Thousand Hands/Eyes (phyag stong spyan stong), Naturally Appeared Holy Dharma Raja Yama (dam can chos rgyal rang byon).

|

| Arol Lobsang Lungrtogs Tenpai Gyaltsen | Gelupa | 1888–1958 | 1. Established the Drakar Dreldzong monastery.

2. Composed The Melodious Praise of Dreldzong. |

| Dobi Geshe Sherab Gyatso | Gelupa | 1884–1968 | 1. Composed The Praise

2. Revealed Sacred Sites 1) Mandalas: the Chakrasamvara Mandala 2) Deities: Avalokiteshvara, Victorious Vajra Holder, Twenty-four Dakinis, King of Dharma, Arya Tara 3) Masters: The Great Leader Jir De gpon, Padmasambhava, Drikung Jigten sum Gon, Labkyi Dronma, Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen, Je Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa, Shar Kelden Gyatso, Serkhangpa, Zhabs dkar tshogs drug rang grol, Lobsang lungrigs Gyatso, Lobsang Lungtog Tenpai Gyeltsen (blo bzang lung rtogs bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan). 4) Sacred Places: Holy Water (grub chu), Mountain Pass of Higher Realm (mtho ris la), The Front Mountain Tara (mdun ri sgrol ma’i ri), Right Mountain (g.yas ri), Left Mountain (g.yon ri), Pure Crystal Mountain (dag pa shel ri), Chenmo Water (chen mo’i chu). |

Appendix 2

- The Pilgrimage Guide to Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong gi dkar chag)

- The Praise of the Melodious Sound of the Right-Turning Dharma Conch for Drakar Dreldzong (brag dkar sprel rdzong gi bstd pa chos dung g.yas su ‘khyil ba’i sgra dbyangs)