Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Oral Cancer: A Litterature Review on Risk Factors and Preventive Health Interventions

Petropoulou P¹*, Artopoulou I2

1PhD(c) in Oncology Nursing, University of West Attica Greece, Dentist – Periodontist MSc

²DDS, MS, PhD Assistant Professor, Dept.of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Received Date: January 17, 2023; Accepted Date: January 31, 2023; Published Date: February 08, 2023;

*Corresponding author: Petropoulou P. PhD(c) in Oncology Nursing, University of West Attica Greece, Dentist – Periodontist MSc. Email: ppetropoulou@uniwa.gr

Citation: Petropoulou P, Artopoulou I (2023) Oral Cancer: A Litterature Review on Risk Factors and Preventive Health Interventions. Adv Pub Health Com Trop Med: APCTM-177.

DOI: 10.37722/APHCTM.2023201

Abstract

Oral cancer is a serious public health problem, due to the frequency and low survival rate of patient. Its incidence has increased 25% in the last 10 years. According to epidemiological evidence oral cancer has multifactorial etiology and is shaped by biological, social, economic, cultural and environmental factors. In developing countries as well as in lower socioeconomic strata, it shows significant increase. Signs and symptoms that should lead to a specialist include ulcers that does not heal within 2 weeks, swelling inside the mouth, white (leukoplakia) or red areas (erythroplakia) that may bleed, oral mucosa thickening, difficulty in swallowing, speaking and opening mouth, swelling of throat. In this work we present a series of evidence that early prevention of the disease, pre-symptomatic control in oral health and awareness of health professionals can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality rates of the disease. Primary Prevention aims at limiting the use of alcohol and tobacco products, reducing exposure to occupational and environmental factors, ultraviolet radiation, vaccination against hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus. Secondary prevention focuses on both self-examination and examination by a specialist for suspected lesions. Where appropriate, a smear or biopsy is taken. The conclusions drawn from the public debate on the matter are firstly, public awareness of oral cancer is insufficient and many patients realize the disease at a late stage. Secondly, screening with systematic clinical examination for early detection of the disease is important, especially in high-risk groups. Moreover, implementation of population-level health promotion strategies has a major impact on reducing the prevalence of oral cancer. Furthermore, equal access to primary oral health structures requires political will, comprehensive financing of health services and initiatives to reduce inequalities, concerning the role of social and physical environmental factors and is an important condition for early diagnosis, survival and quality of life. Finally, the possibility of detecting suspicious lesions with high reliability with telemedicine methods, with the aim of clinical examination and recognition of oral lesions by trained dentists and health workers, can significantly contribute to reducing the frequency of the disease, in areas where it is impossible to access primary health structures.

Keywords: Oral cancer; oral screening; oral health; preventive health interventions; risk factors; telemedicine

Introduction

Oral cancer is a serious public health problem among global population, especially in developing countries, due to the frequency and low survival rate of patient. Its incidence has increased 25% in the last 10 years [1].

Oral cancer has multifactorial etiology and is shaped by biological, social, economic, cultural and environmental factors. In developing countries as well as in lower socioeconomic strata, it shows significant increase. It is a global health issue with substantial morbidity and a high mortality rate mainly because of late-stage diagnosis [2].

There is strong evidence that tobacco, alcohol consumption and obesity increase the risk of oral cancer, while there is some evidence that eating non-starchy vegetables, coffee and choosing healthy eating patterns can reduce the risk of oral cancer [3].

It is estimated that as much as 90% of mouth cancers worldwide are attributable to tobacco use, alcohol consumption or a combination of both. In addition, oral infection with high-risk human papilloma virus and environmental exposure to asbestos are associated with an increased risk of mouth and oral cancers [4].

Sharp teeth, trauma from dentures, poor oral hygiene are also locally irritated causes that increase the risk of malignant transformation. Other important risk factors are the presence of potentially malignant lesions and conditions in the mouth and a previous history of oral cancer or upper respiratory tract cancer [5]. Ulcers, external and internal lesions, white and red areas are the most common clinical images of oral cancer. Hardness on palpation at the periphery of the lesion is characteristic and its observation raises clinical suspicion [6].

Oral cancer is linked to poverty. Both within and between countries, the prevalence and distribution of risk factors parallels the socioeconomic development of the population. The greatest burden of oral cancer is among lower socioeconomic groups because they are more exposed to risk factors and have limited access to prevention and treatment [7]. Oral cancer rates in India are 25% and 80% are diagnosed in advanced stages. There is a need for a strategic screening and literature review to provide information and knowledge about oral cancer screening programs in primary care settings [8].

Possible localizations of oral cancer are the lower lip, the tongue, the mouth floor, the cheeks, the gums, the palate. Signs and symptoms that should lead to a specialist include ulcers that does not heal within 2 weeks, swelling inside the mouth, white (leukoplakia) or red areas (erythroplakia) that may bleed, oral mucosa thickening, difficulty in swallowing, speaking and opening mouth, swelling of throat [9,10]. Most of the lesions were found on the buccal mucosa, retromandibular triangle and palate and most of lesions were white lesions, categorized as traumatic [1].

According to previous research, 70% of oral cancer cases are diagnosed at an advanced clinical stage. This is due to a lack of patient information combined with insufficient training of health professionals which are usually the main reasons for late diagnosis of oral cancer [2, 5]. Also according to studies around the world, the known risk factors associated with oral carcinogenesis show that more than 80% of all oral cancers can be prevented [11].

Purpose

The purpose of this narrative study is to investigate health strategies for early prevention of oral cancer and to increase awareness of patients and health professionals for coping the disease.

Methodology

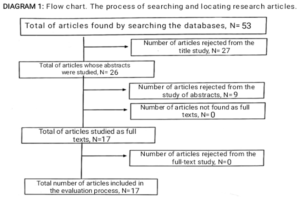

Literature review of studies 2017-2022 in PUBMED with key words «oral cancer» and «prevention health interventions» and «screening» and «risk factors». 53 were found, 17 were included in this study according to the selection criteria of the study. Limitations of the study The fact that the present review was limited to the English-language literature is a limitation of the work since it has not been investigated whether there are studies published in another language, which were not identified. Also a limitation of the work is the time limitation, the fact that the search for the articles was done only in one database and no systematic error control was performed.

Results

Primary Prevention aims to reduce exposure to risk factors: tobacco, alcohol, occupational and environmental factors, ultraviolet radiation, hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus with vaccination and helps to improve the five-year survival rate of patients, which in recent decades has consistently remained below 50% [1,3].

The diagnostic delay of oral cancer is divided into «patient delay» and «professional delay», which is why preventive campaigns are recommended according to age, factors risk, the social economic situation and the importance of a valid diagnosis thus increasing the awareness of the population and health professionals. It is recommended a mass action of awareness campaigns that can be carried out at different levels, starting with health professionals5 and reaching public and state institutions [4].

Secondary prevention focuses on both self-examination and examination by a specialist for suspected lesions. Where appropriate, a smear or biopsy is taken for cytological or histological examination respectively. Treatment delay longer than 6 weeks for oral cancer detected via a population -based screening program had unfavorable survival [12]. Although treatment is associated with better survival, the stage of the cancer and the location of the cancer are decisive factors after malignancy is confirmed. Delay in treatment can be managed by referral for urgent treatment to facilities with such capacity as to avoid worsening prognosis [12].

Public awareness of oral cancer is insufficient and many patients realize the disease at late stage while early detection significantly reduces morbidity and mortality rates [8]. Patients are generally aware of the risk of oral cancer associated with tobacco but knowledge of other risk factors is limited. Thus, an improvement in health literacy is identified in relation to oral cancer and its treatment methods. Most patients do not appear to receive advice about chronic disease prevention during a dental visit except for tobacco users and obese people who report receiving counselling [9, 12]. Chronic disease screening in dental offices through medical history taking could target risk factors and risk groups of patients for better health promotion and promotion of chronic disease prevention [9].

Screening high-risk populations and implementing telemedicine by specialists can reduce costs and increase efficiency; however, there is poor implementation of screening programs at Primary Health Care (PHC) [11]. With screening methods, oral cancer can be detected and treated in precancerous stages, so there is a need to include and implement affordable screening programs, especially in areas that are not served by cancer services and in high-risk groups [2, 13].

Implementation of population-level health promotion strategies has a major impact on reducing the prevalence of oral cancer. Today’s technology allows for teleconsultation as well as instant and easy sharing of digitized images with widely available Smartphone cameras [6]. This may open the potential for remote oral mucosal screening programs with a multidisciplinary approach and involving pathologists, speech therapists, nurses and other health professionals [14].

Τhe combination of adjuncts to augment visual examination or the use of saliva/blood-based tests using proven bio markers, has not been explored in primary care and could be incorporated into future oral cancer screening research programs [15, 16].

An increase in the proportion of the population with access to adequate Oral Care is required, for early detection and screening, as well as the use of Health Care Information Systems for this purpose [7, 17].

Discussion

This study explores health behaviors and strategies that can be followed for the prevention and early detection of oral cancer [1]. It also captures patients’ lack of information about oral cancer and the risk factors that cause it [7], as well as the lack of systematic monitoring of patients by health professionals for early diagnosis and better prognosis of oral cancer [2].

In general, based on the findings of the review oral cancer is associated with health behaviors that can be changed [11, 17]. It also seems that the prognosis for patient’s survival is directly affected by the type and stage of oral cancer [6].

Other research studies also have shown that the socioeconomic status of patients with oral cancer is directly related to primary and secondary prevention and early diagnosis by health professionals [3, 5]. Additionally, with primary and secondary prevention, screening has proven to be an extremely important tool for prevention and valid diagnosis of oral cancer, which can be used by health professionals in combination with new technologies, especially in high-risk groups and in patients with difficulties accessing primary health care structures [13].

Furthermore, promoting public awareness and conducting preventive educational campaigns may increase the number of people who present to primary care with early disease and result in reducing the presentation of disease at an advanced stage [4].

Moreover, undergraduate training in dentistry and continued education courses should focus on the identification and prevention of oral cancer and other potentially malignant disorders [9].

Therefore, these measures combined are of the utmost importance to decreasing morbidity and mortality due to oral cancer [16].

Finally, quantitative assessment of the relation between the cognitions of dentists and their behavior is required as well [14]. The oral cavity is easily accessible for screening and with the new technology it is possible to perform risk assessment and monitoring of oral lesions. However, further research should be conducted to verify if such a strategy for telemedicine really helps to improve morbidity and survival [12].

Further research also is needed to explore in what ways equal and timely access to primary care facilities can be achieved as well as greater public awareness of health behaviors that promote oral health and quality of life [15]. Health professionals combined with technology can play a dominant role in awakening and educating the public to prevent and deal with the disease [8, 10].

Conclusions

Scientific and political actions are needed to reduce inequalities and promote health strategies since the impact of the physical and social environment on health has already been identified for early diagnosis, survival and quality of life.

Simultaneously, the possibility of detecting suspicious lesions with high reliability with telemedicine methods, by trained dentists and health workers, can significantly contribute to reducing the frequency of oral cancer, especially in areas where it is impossible to access primary health structures.

References

- Kwaśniewska A, Wawrzeńczyk A, Brus-Sawczuk K, Ganowicz E, Strużycka I (2019). Preliminary results of screening for pathological lesions in oral mucosa and incidence of oral cancer risk factors in adult population.Przegl Epidemiol. 73:81-92.

- Fleming E, Singhal A. Prev Chronic Dis. Chronic Disease Counseling and Screening by Dental Professionals: Results From NHANES, 2011-2016.2020 Aug 20;17:E87.

- Shimpi N, Jethwani M, Bharatkumar A, Chyou PH, Glurich I, et al. (2018). Patient awareness/knowledge towards oral cancer: a cross-sectional survey.BMC Oral Health. May 15; 18:86.

- Lan R, Campana F, Tardivo D, Catherine JH, Vergnes JN, Hadj-Saïd MBMC Oral Health. Relationship between internet research data of oral neoplasms and public health programs in the European Union. 2021 Dec 17; 21:648.

- Rindal DB, Mabry PL.J Pers Med. Leveraging Clinical Decision Support and Integrated Medical-Dental Electronic Health Records to Implementing Precision in Oral Cancer Risk Assessment and Preventive Intervention.2021 Aug 25; 11:832.

- Su WW, Lee YH, Yen AM, Chen SL, Hsu CY, Chiu SY, Fann JC, Lee YC, Chiu HM, Hsiao SC, Hsu TH, Chen HH.Impact of treatment delay on survival of oral/oropharyngeal cancers: Results of a nationwide screening programHead Neck. 2021 Feb; 43:473-484.

- Jafer M, Crutzen R, Moafa I, van den Borne B.What Do Dentists and Dental Students Think of Oral Cancer and Its Control and Prevention Strategies? A Qualitative Study in Jazan Dental School. J Cancer Educ. 2021 Feb; 36:134-142.

- Ortblad KF, Kearney JE, Mugwanya K, Irungu EM, Haberer JE, Barnabas RV, Donnell D, Mugo NR, Baeten JM, Ngure K.HIV-1 self-testing to improve the efficiency of pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery: a randomized trial in Kenya. 2019 Jul 4; 20:396.

- Wimardhani YS, Warnakulasuriya S, Wardhany II, Syahzaman S, Agustina Y, et al. (2021). Knowledge and Practice Regarding Oral Cancer: A Study Among Dentists in Jakarta, Indonesia.Int Dent J. Aug; 71:309-315.

- Lin I, Datta M, Laronde DM, Rosin MP, Chan B (2021). Int Dent J. Intraoral Photography Recommendations for Remote Risk Assessment and Monitoring of Oral Mucosal Lesions.2021 Oct; 71:384-389.

- Jafer M, Crutzen R, Ibrahim A, Moafa I, Zaylaee H, et al. (2021). Using the Exploratory Sequential Mixed Methods Design to Investigate Dental Patients’ Perceptions and Needs Concerning Oral Cancer Information, Examination, Prevention and Behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jul 16; 18:7562.

- Patil AD, Salvi NR, Shahina B, Pimple AS, Mishra AG, et al. (2019). Perspectives of primary healthcare providers on implementing cancer screening services in tribal block of Maharashtra, India.South Asian J Cancer. 2019 Jul-Sep; 8:145-149.

- Leonel ACLDS, Soares CBRB, Lisboa de Castro JF, Bonan PRF, Ramos-Perez FMM, et al. (2019). Knowledge and Attitudes of Primary Health Care Dentists Regarding Oral Cancer in Brazil. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2019 Mar; 53:55-63.

- Riccardo Nocini, Giorgia Capoca Daniele Marchioni Francesca Zotti. A Snapshot of knowledge about Oral Cancer in Italy: A 505 Person Survey. PMID; 32645880.

- Güven DC, Dizdar Ö, Akman AC, Berker E, Yekedüz E (2019). Evaluation of cancer risk in patients with periodontal diseases. J Med Sci. 2019 Jun 18; 49:826-831.

- Mohan P, Richardson A, Potter JD, Coope P, Paterson M (2020). Opportunistic Screening of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: A Public Health Need for India.JCO Glob Oncol. 6:688-696.

- Giraldi L, Leoncini E, Pastorino R, Wünsch-Filho V, de Carvalho M, et al. (2017). Alcohol and cigarette consumption predict mortality in patients with head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis within the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) Consortium. Ann Oncol. Nov1; 28:2843-2851.