Publication Information

ISSN: 2641-6816

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2018

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Linking Food Endorsement Labels & Messaging to Perceived Price and Emotions. A Mind Genomics® Exploration

Aurora A Saulo1*, Howard R Moskowitz2, Attila Gere3, Petraq Papajorgji4, Linda Ettinger Lieberman5, Dvora Feuerwerker6

1Department of Tropical Plant & Soil Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM), USA

2Mind Genomics Associates, Inc.11 Sherman Ave., White Plains, NY 1060, 5USA

3Department of Postharvest Science and Sensory, Evaluation H-1118, Budapest, Villányi út, 29-43, Hungary

4Department of Informatics and Technology, European University of Tirana, Albania, Blv Gjergj Fishta, Nd., 70, H.1. 1023 Tirana, Albania

5Independent Researcher, 63 Alex Drive, White Plains, NY 10605 USA

6Independent Researcher, 65 Pomander Drive, White Plains, NY 10607, USA

Received Date: October 24, 2019; Accepted Date: October 29, 2019; Published Date: November 07, 2019

*Corresponding author: Aurora A Saulo, Department of Tropical Plant & Soil Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa (UHM), 3190 Maile Way, St John 102, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA. Tel: +18082261950; Email: aurora@hawaii.edu

Citation: Saulo AA, Moskowitz HR, Gere A, Papajorgji P, Lieberman LE, Feuerwerker D (2019) Linking Food Endorsement Labels & Messaging to Perceived Price and Emotions. A Mind Genomics® Exploration. Adv Nutri and Food Sci: ANAFS-152.

Abstract

Respondents evaluated systematically created vignettes (short combinations), comprising actual logos, along with messages. The approach, Mind Genomics, allows each respondent to evaluate a unique set of combinations, rating each combination on two attributes, appropriate price and feeling/emotion best describing one’s feeling after reading the vignette. The experimental design uncovers the relation between the presence/absence of the 36 elements (including logos and messaging), and both the selected price and linkage to positive and negative emotions, respectively. The results were analyzed for total panel, gender, those who identified themselves as halal or kosher, respectively, and emergent mind-sets.

The authors concluded that the use of the Mind Genomics approach did not produce clear segmentation when the respondent made a judgment of price or emotion. They were just different. Halal users were willing to pay much more for halal food and those with labels that stress the Muslin Qur’anic origin than were kosher users. The Torah origin of kosher did not dramatically increase the price willing-to-pay of kosher users. Halal users appeared to be more positive toward halal food, than kosher users including when they read about halal. Thus, the strongest relations emerged from respondents who identified themselves as halal users. The application of Mind Genomics to any aspect of everyday life expands many types of scientific studies.

Keywords: All-natural; Halal; Kosher; Locally Grown; Mind Genomics; Non-GMO; Sustainable; USDA Organic; Vegetarian

Introduction

At the time of this writing (May, 2019), the focus of the food industry world-wide is on the food label, and specifically a clean label. For 65% of consumers, a clean label consists of the fewest number of ingredients (usually not more than five). Fifty eight percent of consumers expect these ingredients to be simple, without chemical-sounding names and can be readily found in a kitchen cupboard. Although the contemporary consumer expects a clean label to reside only with less processed foods and beverages, they heavily interrelate their concept of a clean label with other product attributes, such as natural, organic, authentic, real, and fresh and may even use these terms interchangeably. Consumers’ concept of natural and organic has evolved to those that for them symbolize healthy (e.g., fresh, safe, local) and are logical and make sense (e.g., less processed, no chemicals, no pesticides, nothing artificial, not high fat/sugar, low in nutrients). The new consumer food culture is a combination of various attributes that in their mind are related to natural and organic, such as ethical practices, sustainable farming, and animal welfare [1].

But the consumer concept of a clean label is not solely based on food attributes or ingredients. Consumers expect the food manufacturer to be transparent with their processing practices. One way to achieve this is through a more complex, more emotionally attached method than simply incorporating good-for-you ingredients, such as the observation of religious practices (e.g., halal and kosher) that consumers equate to high food standards of quality.

Labels and messaging signify many things. One objective of this study is to determine how the nine logos and messaging below drive consumer feeling. The logos and messaging are holistic, carrying the insignia of religious tradition, of health benefit, and of ecological sensitivity such as USDA Organic, Certified OU Kosher, and Sustainable Certified.

- All Natural

- USDA Organic,

- Non-GMO Verified

- Gluten All Free2

- Vegetarian

- Sustainable Certified

- Locally Grown

- Certified OU Kosher

- Halal International

Another objective is to study different messaging about foods, ranging from what the food is, to authority and heritage about the food, in order to capture the impact of the verbal message as well as the impact of the logo. The application of Mind Genomics to any aspect of everyday life and of consumer behavior expands this field of scientific studies.

Background

A food product attracts consumer’s attention in various ways. It may be the product name, the vignette, the brand name, or even an advertisement that motivated the consumer to shop for the product. The consumer may also intentionally seek a new product due to a request from a family member, a friend or another consumer. The product can also attract the consumer at point of purchase, even without the consumer having any prior knowledge of the product.

The product label is one of the earliest points of information for a food. Simply using the right messages and the right pictures may suffice to intrigue the shopper to reach out and put the product in the basket. With today’s increasing use of the Internet for shopping, the label may be even more important as a driver of purchase, since the consumer has no way of knowing about the product unless the product has been previously experienced personally or through reviews of other people.

Labels, especially those which are general and do not belong to a specific brand, may carry additional important signals to the prospective buyer that there is something special about the product, such as imputed eco-friendly (e.g., organic), acceptable to devotees of a specific religious practice (e.g., halal or kosher), or healthful for those suffering from a condition (e.g., Gluten All Free2 for those who require gluten free.). The list of messaging which serve as approbations is long and support what consumers now define as clean.

Labels, logos and messaging are an early moment of truth, when a consumer is told about a product or sees a product in the store. There are many aspects of the label. The quantitative study of labels and messaging has been the subject of many scientific papers. The topics are varied and extensive, including nutrition labels [2], food safety [3], nutrition information and food choices [4], brand name and acceptability of pasta [5], and behavioral correlates with food label use [6].

There is also an increasing interest in halal and kosher as seemingly divinely design quality designations [7-9]. Muslims are the fastest-growing faith-based consumers in the world and their needs go beyond dietary goods. Modern halal is now interpreted as in the same category as the organic, fair-trade, sustainability, and all-natural industries bringing it at easy-reach of the mainstream consumer and creating a global market that is estimated to be $2.1 trillion annually [10].

Shoppers can be critical, and the cost of a food product may be prohibitive to some shoppers. With the focus of economics in mind, the question addressed here is in part, the dollar value of the label. That is, when different labels are put onto statements about products and presented to respondents as combination of labels and messaging, would respondents be willing to pay more than they would for those combinations without the label? In other words, what is the dollar value of the label, if any? The topic on willingness-to-pay has been explored in publications, some on food packaging [11] and others that rely on a link with luxury, such as wine [12, 13]. Different logos [14] for the same certification program elicited varying willingness-to-pay because consumer perceptions of the labeling schemes were not based on objective information.

These studies report only some of the commonly followed practices of flogging labels and messages in order to drive purchase. There are many other publications on the meaning of logos, labels, and messaging that are in private corporate reports instead of the published scientific literature.

Method

Mind Genomics®, a newly emerging science that attempts to uncover the criteria by which people make decisions, is the chosen approach for this study. The underlying world-view of Mind Genomics® is that in any area of human activity, where there is a subjective component (e.g., response to food labels), people can be considered as assigning a weight to each feature of the activity [15, 16]. The assignment of the weight is almost automatic, in the fashion of Kahneman’s System 1 thinking [17]. Indeed, respondents often cannot consciously tell the interviewer their own weighting scheme, yet the pattern of their responses can be deconstructed to reveal a pattern which often matches the pattern of their responses quite well.

Mind Genomics® follows a choreographed series of steps described below to create test stimuli, test those stimuli with respondents, and analyze the data to reveal patterns or weightings of alternative stimuli.

- Create the Raw Materials: In this study, the raw materials can be thought of as silos (questions) and elements (answers). Four silos are set up as questions to be answered, and nine answers or elements are selected for each question. Table 1 shows the 36 elements (4x9). These 36 elements or answers to questions will later be combined into 60 unique combinations, each combination comprising a vignette. The feasible limit of 36-40 elements was reached, recognizing that the maximum number of vignettes that can be expected of a respondent to evaluate is approximately 60-70, unless the respondent is well-compensated.

The four silos, created as questions, appear in (Table 1). The role of the question is to help the researcher in framing the answers or elements. It will be the answers (elements) that will become the building blocks of the vignettes. The silos (questions) will never appear.

| What is the label (in graphic form)? | |

| A1 | All Natural |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher |

| A3 | Gluten All Free2 |

| A4 | Halal International |

| A5 | USDA Organic |

| A6 | Vegetarian |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified |

| A8 | Locally Grown |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified |

| What is the product? | |

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook |

| B2 | Ready-to-eat soup ... just heat and serve |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies |

| What is the label (in graphic form)? | |

| B4 | Spices, herbs and other flavor enhancers |

| B5 | Packaged pre-washed ready-to-serve salad ... just add dressing and toppings of your choice |

| B6 | Bottled juice |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce |

| What is the origin of the product – historically, or in terms of immediate acquisition? | |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt |

| C2 | From a local street vendor |

| C3 | Manufactured by a well-known, national food company |

| C4 | Look for it in your neighborhood grocery store |

| C5 | Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place ... convenient |

| C6 | Prepared by people who share your cultural and religious values |

| C7 | In line with values in the Torah |

| C8 | In line with values in the Qur'an |

| C9 | Based on sacred teachings ... not your faith, but shares your values |

| What are additional messages of appropriateness or authority? | |

| D1 | Traveling ... perfect time to try new foods |

| D2 | Endorsed by an environmental watchdog organization |

| D3 | Ingredient list reflects claim on the label |

| D4 | Regularly inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture and religious authorities |

| D5 | Label is prominently displayed ... easy to read |

| D6 | Healthful and permitted by religious teachings ... a winning combination |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) |

- Create an Experimental Design for Each Respondent: The experimental design comprises 60 vignettes or combinations. Each combination comprises 2-4 elements, with a maximum of one element from each of the four silos (questions.) This strategy ensures that the respondents will never see combinations which present directly conflicting information. The experimental design ensures that the 36 elements are statistically independent of each other, that each element appears an equal number of times, and that ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression can be performed on the results of each individual respondent to show the contribution of every one of the 36 elements to the dependent variables.

- Actual versus Potential: The actual information presented in the vignette may or may not be real, however. For the most part, the respondent does not know this, nor even care. It is this feature that allows the Mind Genomics® system to become an invention machine, combining hitherto uncombined ideas into possibly new-to-the-world product ideas.

- Create a Set of Permuted Designs: Create a set of 200 permutations of the basic experimental design, keeping the design structure the same, but ensuring that the combinations differ from respondent to respondent. This approach allows Mind Genomics® to test more of the alternative combinations that could be made [18]. Most conventional methods using experimental design, the so-called conjoint measurement methods, rely upon one single experimental design and many respondents to ensure that the responses are stable, and that there is a precise measure of the mean response to each combination [19]. Mind Genomics® does the opposite, by covering a wide space, albeit with less precision for each point. The far greater coverage, i.e., the greater space-filling nature of Mind Genomics® provides a potentially more accurate measure of the pattern of responses. Furthermore, Mind Genomics® more validly estimates the contribution of each element, which is presented against a background of many different combinations of other elements. In other words, Mind Genomics® sacrifices high precision and low coverage for low precision and high coverage, respectively.

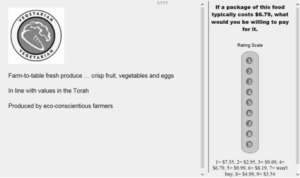

- Create Easy-to-Read Combinations, following the Experimental Design: The first silo or question used in the study was the actual logo itself and in color. (Figure 1) shows an example of a vignette with the combination of elements to the left, and the first rating question (price would pay) on the right. The vignette is easy to read, which makes the experiment easy to run. Instead of having the different messages put together in the form of a paragraph, the Mind Genomics® system puts the messages in stacked, centered form. This format, without connectives to link the elements, allows the respondent to search through the information without being confronted with a dense, possibly formidable-looking paragraph of words, a format which might discourage searching through the test stimulus before answering the rating questions.

Figure1: Example of a vignette and the rating scale (Question 1: Price). The rating scale gives the respondent a sense of a ‘generally’ appropriate price.

- Ratings: The respondent rated each vignette on two questions. The first question required the respondent to select a price from nine different prices. The prices were presented in irregular order, and a price was given as the anchor ($6.79). The anchoring is important for price because of the different types of products presented by Silo B. The second question required the respondent to select one of five feelings/emotions to correspond to one’s feeling after the reading the vignette. The respondent sees each of the 60 vignettes, and for each vignette rates the two questions. When the first question is answered, the rating scale disappears, and is replaced by the second rating scale. The vignette, however, remains unchanged on the screen.

- Respondents: The respondents were members of an on-line panel, who are rewarded for participating. The respondents participate under totally anonymity, but at the end of the experiment, i.e., the evaluation of the 60 vignettes, the respondents completed a self-profiling questionnaire which provides information about who the respondent is, what the respondent does, and what the respondent believes. The extensive data that were obtained are not presented here. The only relevant pieces of information for this study are the self-defined key groups of the total panel (165 respondents), gender (81 males, 84 females), and religion-based food consumption (11 halal, 12 kosher).

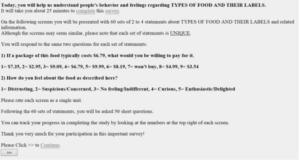

- Orientation: At the start of the experiment, those respondents who agree to participate see an orientation page, shown in (Figure 2). Not much information is given during the orientation but the respondent is given sufficient information about what to do, about the rating scales, and the requirement that the respondent consider all elements in a single vignette as part of the same concept that they will rate. There are two important pieces of information in the orientation which can forestall problems of interpretation that discourage respondents, if not outright anger them:

- Many respondents feel that they would like to rate each of the elements in the vignette. The orientation statement forestalls this temptation by telling the respondent to think about all the information as one idea,

- The respondents often complain that they have somehow seen the vignette before. This is a natural response because each of the 36 elements appears several times, even though the combinations are unique. The respondent must be told ahead of time that all the test vignettes are different. This piece of information, in turn, generally forestalls this irritation.

Figure 2: The orientation page seen by the respondent at the start of the experiment, wherein the respondent evaluates the 60 systematically varied vignettes on the two rating scales.

- Modeling the Contribution of Elements to the Selection of Price: The ratings for price were converted to the actual dollar value, with a small random number added to each dollar value. The small random number does not affect the subsequent data analysis using OLS regression. A grand model was created combining the data for all 60 vignettes for each respondent defined as a member of the key subgroup. For all respondent data from each key subgroup, a dummy variable regression was computed relating the presence/absence of the 36 elements to the dollar value that the respondent selected. The model comprised 36 coefficients, one for each element. The model was created to go through the origin, i.e., with an additive constant forced to be 0. The rationale was that without any features, the respondent would not pay anything for the product.

- Modeling the linkage between element and feeling/emotion. The selection of feeling/emotion required a different analysis because the second rating question is not a scale in the traditional way we think of scales. Rather, the second rating question is an example of a so-called nominal scale, in which every scale point represents a different option, with the options not related to each other in a numerical way. Three new variables were created. The first variable was for the positive emotions (curious, enthusiastic/delighted), the second for the negative emotions (distrusting, suspicious/concerned), and the third was for indifference. One of the five feelings/emotions was selected for each vignette. The variable corresponding to that feeling/emotion was then transformed to 100, and the remaining two variables corresponding to the feelings/emotions that were not chosen were transformed to 0. A small random number was added to all three numbers. Two regression models were computed, one for the newly-created variable encompassing the two positive emotions (curious, enthusiastic) and the other for the newly-created variable encompassing the two negative emotions (distrusting, suspicious/concerned).

Results and Discussion of Results

Total Panel

(Table 2) shows the average coefficients for the 36 elements, broken out by silo (column). Column C shows the average dollar value for each element. Columns D and E show the linkage between each element and both the positive emotions and the negative emotions, respectively.

| $Price, | Positive Emotion | Negative Emotion | ||

| Silo A – What is the label (in graphic form)? | ||||

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 1.87 | 21 | 4 |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 1.79 | 20 | 3 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 1.74 | 19 | 4 |

| A8 | Locally Grown.jpg | 1.64 | 19 | 5 |

| A1 | All Natural.jpg | 1.58 | 16 | 8 |

| A6 | Vegetarian.jpg | 1.43 | 13 | 6 |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 1.39 | 13 | 7 |

| A3 | Gluten All Free2.jpg | 1.34 | 10 | 9 |

| A4 | Halal International.jpg | 0.92 | 8 | 13 |

| Silo B – What is the product | ||||

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 2.08 | 28 | -2 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 1.98 | 25 | -1 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 1.91 | 27 | -1 |

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook | 1.72 | 12 | 8 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 1.5 | 21 | 1 |

| B4 | Spices, herbs and other flavor enhancers | 1.21 | 15 | 5 |

| B5 | Packaged pre-washed ready-to-serve salad ... just add dressing andtoppings of your choice | 1.15 | 14 | 2 |

| B6 | Bottled juice | 1.04 | 14 | 2 |

| B2 | Ready-to-eat soup ... just heat and serve | 0.99 | 14 | 6 |

| Silo C- What is the origin of the product – historically, or interms of immediate acquisition? | ||||

| C3 | Manufactured by a well-known, national food company | 1.47 | 15 | 5 |

| C5 | Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place ... convenient | 1.42 | 16 | 6 |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt | 1.39 | 13 | 6 |

| C4 | Look for it in your neighborhood grocery store | 1.32 | 13 | 6 |

| C6 | Prepared by people who share your cultural and religious values | 1.17 | 12 | 10 |

| C2 | From a local street vendor | 0.95 | 11 | 20 |

| C9 | Based on sacred teachings ... not your faith, but shares your values | 0.87 | 6 | 15 |

| C7 | In line with values in the Torah | 0.34 | 0 | 18 |

| C8 | In line with values in the Qur'an | 0.32 | -4 | 25 |

| Silo D: What are additional messages of authority? | ||||

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 1.68 | 21 | 1 |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) | 1.6 | 20 | 3 |

| D5 | Label is prominently displayed ... easy to read | 1.55 | 12 | 5 |

| D4 | Regularly inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture and religious authorities | 1.49 | 17 | 4 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 1.45 | 17 | 5 |

| D2 | Endorsed by an environmental watchdog organization | 1.43 | 11 | 5 |

| D3 | Ingredient list reflects claim on the label | 1.42 | 13 | 4 |

| D1 | Traveling ... perfect time to try new foods | 1.35 | 13 | 5 |

| D6 | Healthful and permitted by religious teachings ... a winning combination | 1.1 | 11 | 11 |

Previous research results with emotion suggest that single emotions linkages around 10 or higher are relevant, whereas linkages of 8 or below are typically accidental. Those values are not, however, fixed. The research on the linkage between the emotion and the element is relatively new.

The Logos

The dollar values of the different logos, i.e., the mark of the authority, vary dramatically, but in ways that are to be expected. The label “USDA Organic” commands the highest price, $2.20, whereas the halal label is worth only $1.02. The striking difference is due to the systematic and organized years of effort by the government and the food industry, leading to the regulated use of a well-known, respected and trusted logo that, in the minds of the consumer, represents a healthier alternative to industrialized agriculture. This belief manifests itself in the higher price that one is willing to pay for organic products. It is important to note that the Mind Genomics® protocol for presenting stimuli and acquiring data prevents the respondent from singling out “USDA Organic” and assigning a high value to that single element. Rather, the strong performance of this label comes from its ability, within a test vignette, to increase the price selected for the vignette. In turn, and not surprising, the feelings/emotions selected for the logos are primarily positive ones (curious, enthusiastic delight), or indifferent.

The Product

When the product is considered as in Silo B (although this was not an objective of the study), results indicate that the respondent would pay more for “All-natural,” “Farm-to-table,” and “hand-made” products. They would pay the least for processed products or ready-to-eat products that are the types of food emerging with the use of various ingredients and modern technology. Convenience is not as important to the consumer as it was in the past. Imputed product quality now supersedes convenience. The term imputed is used because there is no mention of product quality in the nine descriptions. The elements once again strongly link with the positive emotions, or strongly link with indifference.

Heritage

The third silo (silo C) incorporates two types of messages, history, and religion, respectively. This silo is called heritage. “Local” is a strong theme although there is a price premium for well-known national brands. The connection with religion is minor (Torah, Qur’an), at least for the total population, perhaps because these latter two elements are relevant only to a small number of the respondents (11 for halal, 12 for kosher, respectively). The elements tend to link to indifference, except for the two religion-based elements, which unexpectedly, link to negative emotions (Torah, Qur’an). Related messagings do not drive a high price either, kosher being valued at $1.39 and halal being valued at $0.92

Miscellaneous

The fourth silo (silo D) comprises messagings that might be considered either from an authority or a recommendation of use. This fourth silo does not represent a formal imprimatur, but provides messages which are more explanatory, and might be considered to be supporting information. No effort was made to ensure an agreement between the elements in the first silo (logos of the official organization), and the supporting messages in the fourth silo. For the most part, the permutation strategy ensures that very few clashes will occur with discordant information. There are no surprises from the fourth silo. The elements commanding the highest price are either socially accepted production (e.g., “eco-conscientious farmers”), or good-for you (“recommended by health professionals”).

Gender Differences

It is commonly accepted that women and men have different tastes and different shopping styles. These differences in the genders often cover the more expensive items, ranging from clothes to cars, and even perhaps vacations and houses. With regard to preferences for food, however, differences among the genders are not as clearly described and may rather shift to stereotypes instead, such women prefer salads and men prefer steaks.

Price

With the extensive amount of data generated, it is best to define cut-off points to make the analysis simpler. For either group, $2.00 signifies strikingly strong performances. For either positive or negative emotions, respectively, +15 or higher signifies very strong linkages with emotions. These cut-off points are higher than shown for the Total Panel but they reduce the wall of numbers to a manageable set of data.

From the obtained data, it is possible to assess the magnitude of differences, especially in price. The data are divided into the price models generated by males versus those generated by females, with the models showing the dollar value of every element. (Table 3) shows the dollar values of the elements which generate an estimated dollar value of at least $2.00, for either males or females, respectively. Across the 36 elements, the correlation is a dramatically high +0.91 between the estimated price that men would pay and the estimated price that women would pay. The correlation may be high, but the data suggest that men are willing to pay more for the same item, and in contrast women are willing to pay less.

| M | F | ||

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 2.32 | 1.92 |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 2.31 | 2.25 |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt | 2.21 | 1.59 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 2.16 | 2.13 |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 2.14 | 2.26 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 2.11 | 1.86 |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 2.11 | 1.98 |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 2.1 | 1.84 |

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook | 2.09 | 1.96 |

Emotion

Emotions in the context of food have been of increasing interest to researchers over the years. At the time of this writing (May, 2019), however, most of the published work on emotion, including this paper, have been descriptive [20-22].

Results in (Table 4) again suggest that men and women show similar patterns of emotional responses toward the different elements. An element generating a strong linkage with positive emotions is likely to demonstrate that linkage for both genders, sometimes slightly stronger among males, sometimes slightly stronger against females. But a clear relation between price and positive emotion has been established.

| Linkage with positive emotion | |||

| M | F | ||

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 27 | 23 |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 26 | 30 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 26 | 28 |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) | 23 | 18 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 22 | 20 |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 20 | 22 |

| C5 | Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place ... convenient | 20 | 13 |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 20 | 22 |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 19 | 21 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 19 | 20 |

| Linkage with positive emotion | |||

| M | F | ||

| A8 | Locally Grown.jpg | 18 | 20 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 15 | 20 |

Price versus Positive Emotions (Total Panel, Males, and Females) and Negative Emotions (Total Panel, Males, and Females)

The price that an element would command may be plotted against the estimated linkage of that element to either the positive emotions (curious, enthusiastic/delighted) or the negative emotions (distrust, suspicious/concerned). Both price and linkage are coefficients from the grand model for a specific key group, whether that group be defined by total panel, or gender. In all cases each group (e.g., male) generates three sets of 36 coefficients each, the first set of coefficients for price, the second set of coefficients for linkage to positive emotions, and the third set of coefficients for linkage to negative emotions.

(Figure 3) shows comparable scatter plots. On any row we see the left-most scatter plot relating the estimated element price to the linkage of the element to the positive emotions, and the right-most scatter plot relating the same element price, this time to the linkage of the element to the negative emotions. The straight fit through the data represents the best fitting linear function relating two variables. What is remarkable is the general parallelism between the comparable slopes for the total panel, males, and females, respectively, first for price versus linkage to positive emotions, and then for price versus linkage to negative emotions.

Figure 3: Scatterplots relating element price (ordinate) versus linkage to positive emotion (left-most figure) or linkage to negative emotion (right-most figure). Scatterplots are for the total panel, and for the genders (male versus female).

Religious Observance (Halal versus Kosher).

One of the motivations for this study was to discover the nature of the differences, if any, between the respondents who said that they observed the rules of halal food versus those who said that they observed the rules of kosher food. Of the 165 respondents who proceeded with this study, 11 respondents classified themselves as observing halal and 12 respondents classified themselves as observing kosher. Although these are relatively small samples, they are sufficient to generate patterns that can be compared to each other. As the data will reveal, there are dramatic differences between these two groups, most clearly when it comes to how they respond to the symbols (logos) of halal versus kosher, and how they respond to the verbiage (messagings) about the Qur’an versus the Torah.

The summary results appear in (Table 5). The elements in the four silos are sorted in descending order of the dollar value assigned by those respondents who identified themselves as observing halal (H). The same structure of columns used for gender was followed, beginning with one group (halal) on the left column of the pair, and to its immediate right the corresponding data for the other group (kosher, K). The third column of data corresponds to the results of the remaining 142 respondents (O) who classified themselves as neither follower of halal nor followers of kosher. As was done with the gender data, the high scoring elements were identified but this time relaxing the criterion for price in order to incorporate elements which are relevant to halal or kosher, but which may not meet the previous stringent criterion of an element that commands $2.00 among any group. The criterion was lowered to $1.60, forcing the inclusion of elements which were directly relevant.

| Price | ||||

| Halal Observers | H | K | O | |

| C8 | In line with values in the Qur'an | 2.81 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 2.15 | 1.48 | 1.93 |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 2.02 | 1.55 | 2.12 |

| A4 | Halal International.jpg | 1.94 | 0.09 | 0.91 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 1.9 | 1.44 | 1.49 |

| A6 | Vegetarian.jpg | 1.88 | 0.95 | 1.43 |

| B4 | Spices, herbs and other flavor enhancers | 1.88 | 0.86 | 1.19 |

| C6 | Prepared by people who share your cultural and religious values | 1.81 | 1.07 | 1.14 |

| D5 | Label is prominently displayed ... easy to read | 1.66 | 0.97 | 1.59 |

| D4 | Regularly inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture and religious authorities | 1.66 | 0.95 | 1.53 |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt | 1.65 | 1.07 | 1.39 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 1.61 | 0.92 | 1.49 |

| Kosher Observers | ||||

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook | 1.5 | 1.84 | 1.7 |

| B5 | Packaged pre-washed ready-to-serve salad ... just add dressing and toppings of your choice | 1.2 | 1.71 | 1.12 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 1.73 | 1.61 | 1.73 |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 1.59 | 1.32 | 1.38 |

| C7 | In line with values in the Torah | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.33 |

| Neither Halal nor Kosher | ||||

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 1.2 | 1.55 | 2.05 |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 1.55 | 0.88 | 1.98 |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 1.24 | 1.06 | 1.89 |

| A8 | Locally Grown.jpg | 1.08 | 0.39 | 1.8 |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 1.78 | 0.64 | 1.76 |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) | 1.68 | 0.99 | 1.67 |

| A1 | All Natural.jpg | 1.43 | 1 | 1.64 |

Halal

Results from (Table 5) indicate that the respondents who observe halal want to pay a higher price for halal and feel more positively to halal than the corresponding respondents who observe kosher want to pay for kosher, and feel about kosher. That is, halal is worth more to halal observers than kosher is to kosher observers.

Kosher

Those who observe the rules of kosher want to pay a lot more for products that have been isolated through packaging, so that there is no chance of contamination with un-kosher foods, a contamination which would render the kosher food unfit to eat. Table 5 shows that for “Packaged meat ... ready to cook,” the model suggests that kosher observers will pay $1.84, whereas for halal observers the model suggests that they will pay less, $1.50. Similarly, for “Packaged pre-washed ready-to-serve salad ... just add dressing and toppings of your choice,” the kosher observer is expected to pay $1.71 whereas the halal observer is expected to pay only $1.20.

Halal Observers and the Qur’an versus Kosher Observers and the Torah

For halal observers knowing that the food is “In line with values in the Qur'an” makes the price very high, $2.81 (Table 5). On the other hand, for kosher observers knowing that the food is “In line with values in the Torah” commands only a price of $0.32. The difference is not due to the values of the Qur’an or the Torah. For kosher observers, it is only the kosher-specific food handling methods that are followed which are relevant, and not the values that are held by those in the role of production or sales.

The linkage of the elements with either positive or negative emotions, respectively, shows the very strong emotional linkages of halal observers with halal and with the Qur’an (Table 6). The linkage with the Halal International logo is +40 among halal observers, only 12 among kosher observers, and only 6 among all others. In the same way, the linkage with the phrase “In line with the values in the Qur’an” is 32 among halal users, and -6 and -7 among kosher users and all others, respectively. Results indicate that the affinity of halal observers to halal and cognate messages (Qur’an) is dramatic.

| Positive Emotion | Negative Emotion | ||||||

| Positive emotions – sorted by halal | H | K | O | H | K | O | |

| A4 | Halal International.jpg | 40 | 12 | 6 | -4 | 22 | 14 |

| C8 | In line with values in the Qur'an | 32 | -6 | -7 | 3 | 16 | 28 |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 31 | 15 | 28 | -2 | -5 | -2 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 29 | 19 | 27 | -8 | 0 | -1 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 28 | 14 | 17 | -2 | 6 | 6 |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 25 | 30 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) | 25 | 13 | 21 | -2 | 12 | 2 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 24 | 15 | 26 | -5 | 9 | -1 |

| D4 | Regularly inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture and religious authorities | 23 | 9 | 18 | -3 | 8 | 4 |

| A6 | Vegetarian.jpg | 20 | 20 | 12 | -1 | -4 | 7 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 20 | 19 | 21 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt | 20 | 9 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 6 |

| Sorted by kosher | |||||||

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 25 | 30 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 18 | 23 | 19 | -2 | 8 | 4 |

| C4 | Look for it in your neighborhood grocery store | 18 | 22 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| A3 | Gluten All Free2.jpg | 3 | 21 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| B5 | Packaged pre-washed ready-to-serve salad ... just add dressing and toppings of your choice | 12 | 19 | 15 | 6 | -7 | 2 |

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook | 10 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 8 |

| Sorted by kosher | H | K | O | H | K | O | |

| D6 | Healthful and permitted by religious teachings ... a winning combination | 16 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 21 | 11 |

| C7 | In line with values in the Torah | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 16 | 19 |

The affinity of kosher observers to kosher is much lower. The kosher logo, Certified OU Kosher.jpg, scores 30 among kosher users and it also scores a relatively high 25 among halal users.

The phrase “In line with values in the Torah” has no positive emotion. As previously explained, for those who observe kosher, it is a matter of the use of kosher food handling methods and not of the linkage of kosher to values. The dramatic differences in the emotional linkage of halal to halal observers, and kosher to kosher observers are again shown, a difference that was pronounced as well with price (Table 5).

Price versus Positive Emotions and Negative Emotions for Halal Observers and Kosher Observers

When price is related to the linkage of elements to positive emotions and to negative emotions, respectively, the same general pattern and slope that were previously observed emerge. That is, the both the positive-sloping lines and the negative-sloping lines have the same slope for the halal observer or the kosher observer. (Figure 4) shows the four scatter plots.

Figure 4: Scatterplots relating element price (ordinate) versus linkage to positive emotion (left-most figure) or linkage to negative emotion (right-most figure). The figure shows the plots for those who declared themselves halal observers versus those who declared themselves kosher observers.

Mind-Sets Based on Price

One of the hallmarks of the Mind Genomics® approach is to uncover underlying groups of ideas which move together and emerge as segments or clusters. That is, the underlying thesis in Mind Genomics® is that for every topic of human experience requiring judgment, there are different groups of people who respond to patterns. Some individuals may respond to messagings about ecology, others may respond to messagings about product features, and still others, as in this study, may respond to messagings about religious values.

Mind Genomics® uses the people to identify these underlying patterns of ideas. It is the pattern of ideas which are of primary interest, but the only way to discover them is by clustering people who hold these ideas and discovering the patterns by seeing which messages or ideas score highest in each cluster. The science is then in the pattern of ideas, not the individual respondents.

When the patterns of the respondents’ coefficients are clustered, segments emerge. In this Mind Genomics® study, respondents are clustered by using either the price that they think is appropriate for each message or the linkage of each element to emotion. The 165 respondents based on their 36 coefficients for price were then clustered. The metric for distance between two respondents was the quantity (1-R), where R is defined as the Pearson correlation coefficient. The quantity R ranges from a perfect linear relation (R=1, 1-R or distance = 0) to a perfect inverse relation (R=-1, 1—1 or distance -2) [23].

Two and three clusters emerged, with the three-cluster solution looking very similar to the two-cluster solution and one cluster showing an additional high-priced element. To be parsimonious but remain meaningful, only the two-cluster solution is presented in (Table 7). The two mind-sets that emerged when respondents were clustered on price were an artisanal/food- oriented mind-set, and an ecology/locavore/health-oriented mind-set. Both mind-sets are approximately of the same size.

| Price- based clusters | |||

| Artisanal and food-oriented n = 87 | Mind-Set 1 | Mind- Set 2 | |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 2.54 | 1.53 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 2.53 | 1.35 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 2.52 | 1.18 |

| B1 | Packaged meat ... ready to cook | 1.9 | 1.49 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 1.88 | 1.04 |

| D5 | Label is prominently displayed ... easy to read | 1.64 | 1.49 |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 1.61 | 2.16 |

| Ecology, locavore, and health-oriented n=78 | |||

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 1.42 | 2.17 |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 1.61 | 2.16 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 1.45 | 2.05 |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 1.42 | 2 |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 0.83 | 1.99 |

| A3 | Gluten All Free2.jpg | 0.76 | 1.97 |

| A1 | All Natural.jpg | 1.23 | 1.96 |

| A6 | Vegetarian.jpg | 0.98 | 1.94 |

| A8 | Locally Grown.jpg | 1.45 | 1.84 |

| C3 | Manufactured by a well-known, national food company | 1.15 | 1.81 |

| C5 | Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place ... convenient | 1.18 | 1.72 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 1.24 | 1.71 |

| D9 | Recommended by health professionals (e.g., doctors, dietitians) | 1.58 | 1.69 |

| C1 | Invited to celebrate a holiday with family ... with a feast no doubt | 1.23 | 1.6 |

Price versus Positive Emotions and Negative Emotions for Mind-set 1 (Artisanal and Food-Oriented) and Mind-set 2 (Ecology, Locavore, Health-Oriented)

When price is related to either positive emotion or to negative emotion (Figure 5), the same pattern previously observed was again obtained. That is, no matter how the respondents are divided, a repeating pattern emerges, with linkages to positive emotions producing an upwards sloping function of an approximately constant slope, and linkages to negative emotions producing a downwards sloping function of an approximately constant value, albeit a slight flatter slope than its counterpart.

Figure 5: Scatterplots relating element price (ordinate) versus linkage to positive emotion (left-most figure) or linkage to negative emotion (right-most figure). The figure shows the plots for the two complementary mind-sets, generated by the pattern of the price values of each of the 36 coefficients.

Mind-Sets Based on Emotions

An individual model for each respondent was computed showing the linkage of each element to the two positive feelings/emotions. The respondents were then clustered using the pattern of their individual linkages of the 36 elements to the positive feelings/emotions. Two interpretable, equal-sized clusters or mind-sets emerged, as (Table 8) shows. Both mind-sets respond to artisanal foods, ecology and locavore (local production). The key difference is that Mind-set 2 also does not respond to the kosher logo, but not to the messagings about kosher, nor to anything that has to do with halal.

| Seg1 | Seg2 | Seg1 | Seg2 | ||

| Mind-set 1 Artisanal and food-oriented (n=77) | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 30 | 25 | -6 | 1 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 28 | 22 | -2 | 1 |

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 26 | 27 | -4 | 1 |

| B9 | Freshly made pasta ... just boil and add your favorite sauce | 23 | 19 | 1 | 2 |

| Mind-set 2 - Ecology, locavore, health-oriented (n=88) | |||||

| B3 | Freshly baked goods ... artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies | 26 | 27 | -4 | 1 |

| D7 | Produced by eco-conscientious farmers | 15 | 27 | 2 | 1 |

| B7 | Farm-to-table fresh produce ... crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs | 30 | 25 | -6 | 1 |

| A9 | Non-GMO Verified.jpg | 15 | 25 | 5 | 0 |

| Seg1 | Seg2 | Seg1 | Seg2 | ||

| Mind-set 1 Artisanal and food-oriented (n=77) | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |

| A5 | USDA Organic.jpg | 17 | 25 | 5 | 2 |

| A7 | Sustainable Certified.jpg | 12 | 25 | 7 | 2 |

| D8 | Follows ecological/environmental guidelines | 12 | 22 | 7 | 3 |

| B8 | Gourmet, hand-made chocolates | 28 | 22 | -2 | 1 |

| C6 | Prepared by people who share your cultural and religious values | 1 | 22 | 18 | 2 |

| A1 | All Natural.jpg | 11 | 21 | 9 | 6 |

| A8 | Locally Grown.jpg | 16 | 21 | 6 | 4 |

| D6 | Healthful and permitted by religious teachings ... a winning combination | 0 | 21 | 22 | 1 |

| C5 | Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place... convenient | 12 | 20 | 9 | 5 |

| A2 | Certified OU Kosher.jpg | 6 | 20 | 14 | 1 |

Interactions – How Do Logos Drive the Response to Other Elements?

Can one message influence another message? That is, does the presence of one element, such as a logo, increase the value of another element? Mind Genomics® presents a way to answer that question with the data already collected. The key to the answer is the structure of the Mind Genomics® experiment, namely that each respondent evaluated 60 different combinations so that at the end of the data, the 165 respondents evaluated 165x60 combinations, most of which differed from each other.

All the test combinations and ratings (price) can be combined into one data set, and the data set is then sorted into 10 strata, one stratum reserved for those vignettes with a specific logo. Thus, there is a stratum for halal, a stratum for kosher, a stratum for non-GMO, etc. There is a tenth stratum, reserved for all vignettes lacking a logo.

Following the above-mentioned division into strata, separate models or equations are computed for each stratum, relating the presence/absence of the 27 remaining elements (non-logos) to the price. (Table 9) shows the coefficients for the ten models. Each column corresponds to one of the strata. The columns are sorted in a descending order, based upon the average of all 27 prices, one per element. Thus, the average price for “Protected Harvest” is highest (average price = $2.36), whereas the average price is lower for “No Logo” ($1.83.)

- The maximum average effect of a logo is about $0.41 and the best performing logo is “Protected Harvest.” The “USDA Organic” logo also commands a high price.

- Food type has a bigger effect ($0.56) on food logo as observed for “Non-GMO Verified.”

- Food preparation does not seem to interact with food logos as indicated by a smaller difference of $0.39.

- Emotions give the biggest effect ($0.65) on food logos as observed for “Protected Harvest” and “Non-GMO Verified.”

Table 9: Interaction between the logo (column) and the message element (row). Numbers in bold represent those in which the logo adds $0.30 or more to the value of the element.Protected Harvest USDA Organic Non GMO Verified Locally Grown All Natural Vegetarian Certified OU Kosher Gluten All Free2 & Allergen Free Halal Food Council No Logo Range, $ Average across elements 2.36 2.32 2.29 2.26 2.25 2.16 2.13 2.08 1.95 1.83 0.41 Avg B (Food Type) 2.48 2.57 2.7 2.54 2.46 2.27 2.42 2.14 2.16 2.17 0.55 Avg C (Preparation) 2.12 2.08 1.74 1.92 2.02 1.83 1.74 1.92 1.86 1.17 0.39 Avg D (Emotion) 2.47 2.31 2.43 2.31 2.27 2.39 2.24 2.18 1.81 2.16 0.65 Category B: Food Types B7 Farm-to-table fresh produce… crisp fruit, vegetables and eggs 2.84 2.73 3.65 3.33 2.37 3.64 3.6 2.46 2.46 2.75 1.28 B8 Gourmet, hand- made chocolates 3 3.69 2.88 2.92 2.47 2.05 2.4 3.05 2.91 2.69 1.64 B3 Freshly baked goods … artisanal breads, cakes, pies and cookies 3.5 3.04 3.04 3.73 3.49 3.32 2.8 2.12 2.61 2.46 1.61 B1 Packaged meat… ready to cook 3.39 3.83 3.19 2.31 1.84 1.9 2.18 1.51 2.71 2.39 2.31 B9 Freshly made pasta … just boil and add your favorite sauce 2.55 1.78 2.44 3.04 2.91 2.75 2.95 1.9 2.04 2.21 1.26 B4 Spices, herbs 2.56 1.8 2.75 1.59 2.24 1.43 2.19 2.67 1.32 1.98 1.43 and other flavor enhancers B5 Packaged pre- washed ready- to-serve salad… just add dressing and toppings of your choice 2.1 1.87 2.13 2.59 1.8 2.05 1.99 1.95 2.04 1.9 0.79 B2 Ready-to-eat soup … just heat and serve 0.71 1.49 1.52 1.74 2.85 1.59 2.12 1.6 2.37 1.6 2.13 B6 Bottled juice 1.68 2.87 2.69 1.66 2.19 1.68 1.59 2.02 1.02 1.59 1.85 Category C: Preparation C3 Manufactured by a well- known, national food company 2.04 2.51 2.84 1.64 2.39 1.64 2 2.18 2.42 1.9 1.21 C1 Invited to celebrate a holiday with family … with a feast no doubt 2.63 2.74 2.29 2.1 2.19 3.06 1.95 1.1 2.02 1.81 1.96 C5 Prepared and packaged for sale right in the same place ... convenient 2.94 2.39 1.83 3.1 1.87 2.28 2.22 2.51 2.18 1.44 1.28 C6 Prepared by people who share your cultural and religious values 2.68 2.38 2.28 1.83 2.16 1.57 2.51 2.61 1.5 1.36 1.17 C4 Look for it in your neighborhood grocery store 2.21 2.17 1.67 2.6 2.63 1.74 2.63 2.57 2.17 1.31 0.96 C9 Based on sacred teachings … not your faith, but shares your values 1.53 1.62 1.61 2.36 1.83 1.54 1.94 1.86 1.27 0.95 1.08 C2 From a local street vendor 2.44 2.03 2.13 1.66 1.94 1.91 1.37 1.99 2.17 0.92 1.07 C8 In line with values in the Qur'an 1.68 1.39 0.27 0.59 2.05 1.42 0.7 0.93 1.64 0.45 1.77 C7 In line with values in the Torah 0.94 1.45 0.74 1.4 1.09 1.34 0.3 1.52 1.39 0.43 1.22 Category D Emotion D7 Produced by eco- conscientious farmers 2.07 3.12 2.76 2.15 2.56 2.49 2.64 1.96 2.02 2.75 1.15 D9 Recommended by health professionals(e.g., doctors, dietitians) 2.53 1.01 2.2 2.2 2.64 3.33 3.11 3.09 2.01 2.29 2.31 D4 Regularly inspected by U.S. Department of Agriculture and religious authorities 1.84 2.73 2.69 3.36 2.57 1.93 1.82 2.69 1.55 2.21 1.8 D3 Ingredient list reflects claim on the label 2.46 2.06 1.76 2.74 1.4 2.19 2.85 1.99 2.12 2.13 1.45 D2 Endorsed by an environmental watchdog organization 2.19 2.63 2.37 2.21 2.59 2.59 1.74 2.12 2.37 2.06 0.89 D5 Label is prominently displayed … easy to read 3.07 2.31 2.34 2.54 2.82 3.24 2.27 1.91 1.89 2.05 1.35 D8 Follows ecological/environmental guidelines 3.39 2.51 3.39 2.14 2.31 2.25 1.14 1.31 1.98 2.02 2.25 D1 Traveling … perfect time to try new foods 2.2 1.41 2.92 1.55 2.1 2.11 2.36 2.37 2.07 2.01 1.51 D6 Healthful and permitted by religious teachings … a 2.44 2.97 1.44 1.87 1.42 1.39 2.19 2.18 0.29 1.86 2.68 winning combination Best combination (scores of the best elements added) 9.52 9.69 9.88 10.2 8.94 10 9.35 8.71 7.7 7.4 Worst combination (scores of the worst) messages added) 3.49 3.89 2.97 3.72 4.29 4.32 3.03 3.75 2.58 3.88 Finding the Appropriate Group (Halal vs. Kosher vs. Other; Mind-set Segment) in the Population

As the science of Mind Genomics® moves from discovery to practical application, one of the issues is to assign new people to the key subgroups that have been discussed above. For example, one may wish to create a tool, the so-called Personal Viewpoint Identifier, to use as a typing tool. A new person might be shown a set of questions, such as those in (Figure 6). Depending upon the data source from which the questions are drawn, the pattern of responses to the question could assign the new person to either a prospective user of halal, kosher, or neither, or a member of Mind-Set 1 or Mind-Set. Rather than repeating the entire, lengthy study, which established the micro-science of the topic, the PVI would simply find use to assign thousands of new individuals to the correct subgroup, either for future knowledge development (research) or for direct, targeted sales, with the correct messaging.

Figure 6: The PVI (personal viewpoint identifier). The pattern of responses assigns a person to the proper group (e.g., Halal vs. Kosher vs. other; Mind Set 1 vs. Mind Set 2)

Conclusions

Clustering Based on Price or Emotion versus Based on InterestResults indicate that Mind Genomics® clustering based upon price or upon selection of emotion does not produce the same clear divisions observed in other studies where the response is interest. Mind-set segmentation of the type used in Mind Genomics® may work when the respondent makes a judgment of acceptance, not a judgment of price or a selection of emotion. When based on liking or interest, the rating may be called homo emotional is that generate divergent segments with dramatically different positive trigger messagings. The trigger messagings, however, are not necessarily opposite to homo emotional is. They are just different. They may be opposite, such as preference patterns for flavor, but they are simply different.

When mind-sets are based upon price, some differentiation is seen as in this study. The two mind-sets seem to be variations on the same theme-- the first is food-oriented and is willing to pay more for artisanal foods, whereas the second is ecology, locavore, and health-oriented but is willing to pay less. There is no dramatic difference among most of the elements between the two mind-sets, as in one group wanting to pay a lot more and the other group wanting to pay a lot less.

The Remarkable Attachment of Halal in Willingness-To-Pay and the Response of Kosher

One of the most remarkable findings of this study is the dramatic attachment of halal users both to the halal logo and to the Qur’anic origins of halal. The respondents who define themselves as consumers of halal food are willing to pay far more for halal food and pay far more for labels that stress the Muslim Qur’anic origin than are kosher users.

Those respondents who define themselves as kosher users are willing to pay a lot more for the kosher logo, and for the stringencies of food production that are guaranteed no contamination. Bringing in the Torah origin of kosher, however, does not dramatically increase the price willing-to-pay.

Results indicate a dramatic difference in the mind-sets of those who observe halal versus those who observe kosher. The former appears far more involved with the positives of halal and feel far more positive emotionally when they read about halal. Those who observe kosher seem to have somewhat less affinity for kosher.

The Remarkable Stability of the Price-Emotion Relation

Scatterplots relating price to the linkage with positive or negative emotions reveal relations with similar slopes. That is, there is no dramatic difference across the total panel, gender, religious observance, mind-sets based on price, and mind-sets based on positive linkages. The results are quite stable, suggesting that there might be an opportunity for an entirely new aspect of behavioral economics using Mind Genomics®, an aspect previously suggested by the name Cognitive Economics [24].

Hedonic Pricing

A growing area of interest is the area of hedonics (likes and dislikes) as they interact with pricing [25]. Data on the relation between price willing-to-pay and linkage with positive versus negative feelings/emotions suggest that there is an approximately constant slope, at least for the topic of food labels of products. The methods of Mind Genomics® as elaborated here allow the creation of evidence to show the relation between the emotions attached to features of a product and the amount that the feature can command. With small scale experiments dealing with the many different of products and services, Mind Genomics® enables the construction of normative databases in a rapid, cost-effective, and scalable fashion. The data presented here with 165 respondents might well have been presented with 30-50 respondents, allowing the same effort of investigation to be spread across four or five topic areas.

Acknowledgment: This research was partially supported by the Premium Postdoctoral Researcher Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Hartman Group (2018) The “Clean Label” Trend: When Food Companies Say “Clean Label,” Here’s What Consumers Understand.

- Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D (2011) Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutrition 14: 1496-1506.

- Saulo AA, Moskowitz HR (2011) Uncovering the mind-sets of consumers towards food safety messages. Food Quality and Preference 22: 422-432.

- Barreiro-Hurlé J, Gracia A, de-Magistris T (2010) Does nutrition information on food products lead to healthier food choices? Food Policy 35: 221-229.

- Di Monaco R, Cavella S, Di Marzo S, Masi P (2004) The effect of expectations generated by brand name on the acceptability of dried semolina pasta. Food Quality and Preference 15: 429-437.

- Kreuter MW, Brennan LK, Scharff DP, Lukwago SN (1997) Do nutrition label readers eat healthier diets? Behavioral correlates of adults’ use of food labels. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 13: 277-283.

- Aziz YA, Nyen VC (2013) The Role of Halal Awareness, Halal Certification, and Marketing Components in Determining Halal Purchase Intention Among Non-Muslims in Malaysia: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 25: 1-23.

- Cheng PLK (2008) The Brand Marketing of Halal Products: The Way Forward. The Icfai University Journal of Brand Management 5: 37-50.

- Mohayidin MG, Kamarulzaman NH (2014) Consumers' Preferences Toward Attributes of Manufactured Halal Food Products. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing 26: 125-139.

- Izberk-Bilgin E, Nakata CC (2016) A new look at faith-based marketing: The global halal market. Business Horizons 59: 285-292.

- Loose SM, Szolnoki G (2012) Market price differentials for food packaging characteristics. Food Quality and Preference 25: 171-182.

- Carew R, Wojciech JF (2010) The Importance of Geographic Wine Appellations: Hedonic Pricing of Burgundy Wines in the British Columbia Wine Market. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D'Agroeconomie 58: 93-108.

- Costanigro M, McCluskey JJ, Mittelhammer RC (2007) Segmenting the Wine Market Based on Price: Hedonic Regression when Different Prices mean Different Products. Journal of agricultural Economics 58: 454-466.

- Janssen M, Hamm U (2012) Product labelling in the market for organic food: Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Quality and Preference 25: 9-22.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic Permuted Experimental Designs and their Application in Conjoint Analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Green PE, Krieger AM, Wind Y (2001) Thirty Years of Conjoint Analysis: Reflections and Prospects. In Wind, Y., Green, P.E. (Eds.) Marketing Research and Modeling: Progress and Prospects. International Series in Quantitative Marketing (pp. S56-S73). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Gutjar S, de Graaf C, Kooijman V, de Wijk RA, Nys A, et al. (2015) The role of emotions in food choice and liking. Food Research International 76: 216-223.

- Spinelli S, Masi C, Dinnella C, Zoboli GP, Monteleone E (2014) How does it make you feel? A new approach to measuring emotions in food product experience. Food Quality and Preference 37: 109-122.

- Desmet PMA, Schifferstein HNJ (2008) Sources of positive and negative emotions in food experience. Appetite 50: 290-201.

- Jain AK, Murty MN, Flynn PJ (1999) Data clustering: a review. ACM Computing Surveys. (CSUR) 31: 264-323.

- Bourgine P (2004) What is Cognitive Economics? In Bourgine P. & Nadal, J.P. (Eds), Cognitive Economics (pp. 1-12). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Didier T, Lucie S (2008) Measuring consumer’s willingness to pay for organic and Fair Trade products. International Journal of Consumer Studies 32: 479-490.