Publication Information

ISSN: 2641-7049

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2018

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Epidemic of False Diagnoses of Autism

David Rowland*

Independent Researcher registered with ORCID, Canada

Received Date: January 21, 2023; Accepted Date: January 30, 2023; Published Date: February 04, 2023;

*Corresponding author: David Rowland, Independent researcher registered with ORCID, Canada. Email: david222@hush.com

Citation: Rowland D (2023) Epidemic of False Diagnoses of Autism. Jr Neuro Psycho and Brain Res: JNPBR-163

DOI: 10.37722/JNPABR.2023101

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to determine the reason for rapidly escalating diagnoses of autism. In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that 1 in 44 children were diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, for a prevalence rate of 2.27% of the population. In 2012, a review of global prevalence of autism found 62 cases per 10,000 people, for a prevalence rate of 0.62 percent. This apparent 266 percent increase in autism prevalence is in stark contrast to all other disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), for which there has been no increase in prevalence over this same six-year period. The increase in alleged autism prevalence from 0.62 to 2.27 percent is entirely due to the DSM-5 creation of a false and overly broad autism spectrum (ASD) catch-all category that includes conditions unrelated to autism. These figures suggest that 70% of those who have been given an ASD diagnosis may not be autistic. What the psychology professions urgently require is a causal based definition of autism, as recommended in this report. Autism is an inherent neurophysiological difference in how the brain processes information and is caused by a dysfunctional cingulate gyrus (CG), that part of the brain which focuses attention.

Keywords: Autism; ASD; Cingulate Gyrus (CG); Hyperfocus; Neurophysiology; Neuropsychology

Introduction

Autism, from the Greek word meaning self, was coined in 1911 by Swiss psychiatrist, Eugen Bleuler, who used it to describe withdrawal into one’s inner world [1]. Autistic children appear to be in a world of their own isolated and alone, with senses that can easily overload. In 1943, psychiatrist Leo Kanner studied the case histories of 11 highly intelligent children who shared a common set of symptoms consistent with autism: the need for solitude, the need for sameness, to be alone in a world that never varied [2]. There is a recently coined word for autism in the Maori language: takiwātanga. It means “in his/her own space” [3].

In 1944, medical professor Hans Asperger studied four boys whom he considered autistic because of their shutting off relations between self and the outside world [4]. Asperger described these boys as having an autistic personality that is an “extreme variant of male intelligence”. He felt that their severe difficulties with social integration were compensated for by the kind of high level of thought and experience that can lead to exceptional achievements in later life.

Epidemic of False Diagnoses

In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that 1 in 44 children were diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, for a prevalence rate of 2.27% of the population [5]. In 2012, a review of global prevalence of autism found 62 cases per 10,000 people, for a prevalence rate of 0.62 percent [6]. This apparent 266 percent increase in autism prevalence is in stark contrast to all other disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), for which there has been no increase in prevalence over this same six-year period.

A 10-year Swedish study in 2015 concluded that although the prevalence of the autism phenotype has remained stable, clinically diagnosed autism spectrum disorder has increased substantially [7]. Phenotyping is based on observing gene expressions in individuals and relating their conditions to hereditary factors. Nowadays professionals diagnose by ticking off symptoms on a checklist, without questioning the possible causes of said symptoms. This is a major step backward from clinical phenotyping.

A 2016 study reported that many children originally diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder were later found not to be autistic [8]. A comprehensive 2019 study in JAMA Psychiatry indicates that autism is being significantly over-diagnosed [9]. Dr. Laurent Mottron, co-author of this study, has expressed these concerns: “The autism category has considerably overextended …most neurogenetic and child psychiatry disorders that have only a loose resemblance with autism can now be labeled autistic … you could not have ADHD and autism before 2013, now you can.” [10] Doctors now tend to label as autistic anyone who simply has ADHD (or OCD) and poor socialization [22].

In 1964, I was misdiagnosed as having a borderline personality disorder (aka emotionally unstable personality disorder) by a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto. The correct diagnosis should have been Asperger syndrome (high functioning autism) [19]. Since then, the diagnostic pendulum has swung far into the opposite direction. False diagnoses of autism are now at an all-time high. Because autism is significantly over-diagnosed, studies relating to the genetic cause of autism are questionable because their correlations may be to conditions other autism [11-13].

The Misleading Spectrum

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association merged the following four disorders under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorder (ASD): autism disorder, Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive development disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). Autism now includes a spectrum of conditions of uncertain similarity.

The American Psychological Association defines autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as any one of a group of disorders typically occurring during the preschool years and characterized by varying but often marked difficulties in communication and social interaction [14]. DSM-5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, describes autism as being characterized by (1) persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction; and (2) restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These criteria are so vague as to be meaningless. If you do not know what causes certain symptoms, then you know nothing about any presumed disorder in question.

The increase in autism prevalence from 0.62 to 2.27 percent in six years is entirely due to the DSM-5 creation of a false and overly broad category that has become a basket catch-all which includes conditions unrelated to autism. If 0.62 percent prevalence represents true autism, then the difference of 1.65 percent prevalence represents conditions that are unrelated to autism. These figures suggest that 70% of those who have been given an ASD diagnosis may not be autistic.

Autistic Traits Have a Single Cause

From intimate knowledge of how my own autistic brain functions, and from studying the behaviors of three autistic family members and 18 other autistic people, I have compiled a list of 50 traits that all 22 of us have in common. These autistic characteristics appear to have a single cause: hyperfocus, the perpetual and unrelenting state of intense single-minded concentration fixated on one thing at a time, to the exclusion of everything else. Hyperfocus thus appears to be the unique and defining causal state of autism that creates all its observed characteristics.

Hyperfocus keeps a person trapped in the mental/intellectual part of his mind with no ability to divide attention between two thoughts, with the consequence that one never gets to feel emotions. S/he can only process emotions intellectually, after the fact. Without the ability to feel emotion, it is impossible to be spontaneous, to be emotionally available, to feel connected to others, or to be aware of how one is perceived. Anthony Hopkins spoke for every autistic person when he is reputed to have said, “My whole life I have felt like an outsider.”

Hyperfocus prevents a person from running two mental programs simultaneously. One takes everything you say literally because s/he cannot also be questioning how you use words. Similarly, an autistic person cannot also be picking up on subtleties or social cues. S/he also cannot lie spontaneously because that would require dividing attention between the truth and a falsehood.

Hyperfocus can be so intense that any sudden interruption (e.g., a door opening, an unexpected question, accidentally dropping something) shatters the thought pattern and can be experienced as anywhere from annoying to devastating. Loud noises instantly switch hyperfocus to the noise, which is then experienced with far more intensity than does someone with a neurotypical brain.

50 Autistic Traits Have a Single Cause: Hyperfocus · Trapped in thoughts · Mind always busy, tendency to overthink · Passionately pursues interests, often to extremes · Amasses encyclopedic knowledge about areas of interest · Self-awareness but no social awareness · Interruptions trigger agitation, confusion, or anxiety · Cannot multitask · Experiences anxiety from being mentally trapped in a sensory assault · Overwhelmed from hearing unwanted conversations · Overwhelmed by too much information · Coping with electronics and filling out forms may cause anxiety · Sensory overload makes it impossible to think or focus · Difficulty listening to radio or talking with others while driving · Processes emotions intellectually · Has generalized physiological responses instead of emotions · Anxiety bypasses the intellect to warn of unprocessed emotions · Incapable of experiencing fear · Can be angry without knowing so · Never (or rarely) cries or laughs · Cannot nurture self psychologically · Shrinks from emotional displays by others · Unable to defend against emotional attacks · Lacks innate desire to socialize · Unaware of feelings, needs, and interests of others · No awareness of how perceived by others · Unaware of socially appropriate responses · Cannot pick up on subtleties, unable to take hints · Unable to read body language · Takes everything literally · Easier to monologue than dialogue · Oblivious to motivations of others while they are speaking · Misses sarcasm · Misses social cues and nonverbal communication · Participating in 3-way conversations may be overwhelming · May have difficulty following topic changes · May understand empathy but unable to feel it · Cannot be emotionally available to others · Others cannot provide an emotional safety net · Innate forthrightness tends to scare others · Never bored, always engaged in some mental activity · Consistent to daily routines, agitated if routine is disrupted · Spontaneity not possible, activities must be pre-planned · Cannot lie spontaneously, can tell only premeditated lies

Hyperfocus is the unique and defining characteristic of autism that is responsible for all 50 of its documented traits listed below [17,18]. Hyperfocus is the perpetual and unrelenting state of intense single-minded concentration fixated on one thing at a time, to the exclusion of everything else.

Mental Traits

· Intense single-mindedness

Sensory Overload

· Hypersensitive to loud noises and bright lights

Emotional Traits

· Unable to feel emotion

Social Traits

· Considers self to be an outsider

In Conversation

· Speaks factually with no trace of emotion

In Relationships

· Understands love intellectually but cannot feel love

Temperament

· Drawn more strongly to certain things than to people

Neurophysiology of the Autistic Brain

Cingulate Cortex/Gyrus

Left Frontal Cortex/Lobe

Right Frontal Cortex/Lobe

Amygdala

Dysfunctional

Dysregulated

Dysregulated

Inactive

The neurological structure of the autistic brain is the same as for every other brain. What is different about the autistic brain is how it functions with respect to its neurophysiology [16,17].

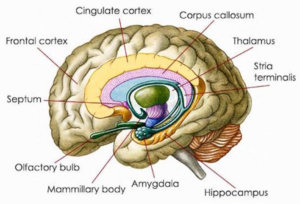

The cingulate gyrus (CG) is that part of the brain which focuses attention. Dysfunction of the CG is the suspected cause of hyperfocus, the perpetual state of intense single-minded concentration fixated on one thing at a time, to the exclusion of everything else.

The amygdala is the region of the brain which plays a central role in the expressing of emotions, especially fear. A dysfunctional CG prevents a person from feeling any emotion, with the result that the amygdala is virtually non-functioning. An autistic person typically never experiences fear.

The left frontal lobe is the intellectual, analytical part of the brain. The right frontal lobe is the emotional/creative processing part of the brain which plays a central role in spontaneity, social behavior, and nonverbal abilities. Some neurotypical people are left-brain dominant while others are right brain dominant. Autistic people are left brain exclusive.

The CG usually acts like an automatic transmission that seamlessly switches attention back and forth between frontal lobes, as required. Unfortunately, the dysfunctional CG in the autistic brain keeps the person permanently trapped in his/her left frontal lobe with the consequence of having to process emotions intellectually.

The EEG neurofeedback I have done on the autistic brain reveals high alpha activity in both frontal lobes. In the neurotypical brain, however, alpha activity (8-12 Hz) is high only in the right frontal cortex, whereas the left frontal cortex reveals high beta activity (12.5-30 Hz). Dominant alpha frequencies in the autistic left brain are most probably compensating for the inability to access creativity from the right brain.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is distinguishing a specific condition from others that have similar clinical features. Based on similar behavior patterns, many with ADHD, OCD and even PTSD have been misdiagnosed as being autistic. However, the neurophysiological differences between autism and such other conditions can be profound.

Both attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) share a common trait, fickle focus, which is defined as intervals of intense mental fixation interspersed with episodes of distraction or impulsiveness. Fickle focus can look like hyperfocus that comes and goes; however, hyperfocus is perpetual and unrelenting. Autistic people never get any relief from their hyperfocus.

Because of the confusion between fickle focus and hyperfocus, many people with ADHD or OCD are misdiagnosed as being on the autism spectrum. Also, some who are truly autistic are given false multiple diagnoses that include either ADHD or OCD or both.

Autism appears to be entirely neurophysiological in origin. ADHD and OCD appear to be caused or aggravated by a biochemical imbalance of neurotransmitters. Low dopamine is suspected in ADHD, and low serotonin is suspected in OCD.

In both autism and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alpha frequencies predominate over beta in the left frontal lobe. In both cases, this phenomenon appears to substitute for being unable to access alpha frequencies directly from the right frontal lobe. The difference is that in PTSD there is a psychological block to remembering horrific emotional events normally accessed from the right frontal lobe, whereas the autistic person is incapable of accessing anything from his right frontal lobe.

A further difference is that ADHD, OCD, and PTSD respond to therapy whereas autism does not. No amount of counseling or behavior modification therapy can talk an autistic person out of hyperfocus. activity activity activity activity fear of disapproval

Autism

PTSD

ADHD

OCD

Hyperfocus

hyperfocus

n/a

fickle focus

fickle focus

Cingulate Gyrus

dysfunctional

functional

functional

functional

Amygdala

inactive

hyperactive

active

hyperactive

Left Frontal Lobe

high alpha

high alpha

high beta

high beta

Neurochemical Imbalance

n/a

n/a

low dopamine suspected

low serotonin suspected

Social Aspects

Unable to understand and respond to the needs of others.

Social skills unaffected by PTSD.

poor social skills

social anxiety,

Emotional Effects

Incapable of feeling emotion. Processes emotions intellectually.

Suppresses memories of emotionally devastating events.

Can trigger intense emotions.

Compulsive behaviors may be attempts to relieve emotional stress.

Autistic Fearlessness

Hyperfocus prevents autistic people from being able to feel emotions as they happen. They can only process their emotions intellectually after the fact, a process that may take 24 hours. By the time an emotion has been processed, it is too late to have been felt.

Nature has programmed into every human being an automated fear response that warns of perceived threats or impending danger. Autistic people are incapable of experiencing this fear response. If you encounter someone who has never felt fear of any kind, this person is most probably locked into autistic hyperfocus.

In every risky, dangerous, or life-threatening situation, the autistic person is always focused on the event itself and incapable of feeling fear or even nervousness in that moment. Sometimes autistic people may intellectualize about fear, for example saying that after thinking about such-and-such decided it could be a scary thing. However, they are incapable of feeling fear.

Anxiety

Anxiety is a physiological response that bypasses the intellect to warn the autistic person about unprocessed emotion. In this sense, anxiety serves as a safety net. Whenever I feel anxiety I stop, take a deep breath; and figure out which emotion is struggling to be acknowledged. Sometimes this involves deduction or running down a mental checklist. As soon as the emotion is named, the anxiety immediately stops [19].

Litmus Test for Autism

Hyperfocus is the unique and defining causal state of autism that creates its observed characteristics. Hyperfocus prevents someone from dividing attention between two thought patterns at the same time. An autistic person talking to you is incapable of feeling any emotion in that moment. The surest way to find out if someone is autistic is to ask these five questions, to which you will receive the following responses [15,17,18].

1.

How often do you cry?

“never” or “rarely”

2.

How often do you laugh?

“never” or “rarely”

3.

What are you afraid of?

“nothing” or an intellectual answer

4.

What are you feeling now?

“nothing” or an intellectual answer

5.

Do you ever get bored?

“never”

Anyone who answers all five questions as above is autistic. Anyone who answers four or fewer as above is not autistic. Note: If the person answers the third question with a phobia (e.g., of heights), then re-ask the question this way, “Aside from this phobia, do you normally experience fear of any kind?”

There is Only One Autism

The autism spectrum notion is counterproductive and needs to be scrapped. A spectrum implies that there can be different kinds of autism and varying shades of autism. Not so. Autism is one thing, and it is 100 percent. Either you are autistic, or you are not.

The only variable within autism is the intensity with which hyperfocus is experienced. Severely autistic people are so intensely locked into hyperfocus as to be unreachable. High functioning autistic people (e.g., those with Asperger syndrome) experience hyperfocus less intensely.

Nonverbal autistic children are so trapped in hyperfocus that there is no known way to bring them out of it. Many autistic children cannot be taught to speak; however, some spontaneously start to speak on their own initiative, as Einstein did at age four.

Absence of Pathology

Autism is simply a neurophysiological anomaly. The only thing different about an autistic brain is the specialized way in which it processes information. As such, autism does not fit the medical definition of disorder, i.e., a pathological or diseased condition of mind or body. Newton, Jefferson, Darwin, Edison, Tesla, and Einstein were most probably autistic and obviously not suffering from any mental pathology [20].

Futility of Therapy

It is not possible to fix that which is not broken. Autism is an inherent way of functioning that cannot be altered. A brain that is trapped in perpetual hyperfocus is incapable of responding to environmental or social pressures. Neither is it capable of responding to behavior modification therapy. No one can be talked out of autistic hyperfocus.

Therapies for autism are aimed at socializing the child. This cannot be done. It is no more possible to socialize an autistic person than it is to intellectualize a neurotypical person. The autistic brain works in a precise way that cannot be altered.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the most common therapy that is forced upon autistic children. It is an intensive one-on-one program that attempts to improve social skills by increasing desirable behaviors and decreasing problematic behaviors. There is a vocal community of adults with autism (many of whom had ABA as children) who say that ABA is harmful because it is based on the cruel premise of trying to make people with autism “normal”.

ABA’s message is that autistic ways of doing things are wrong and need to be corrected, and that the autistic child is broken and must be molded to be more palatable to non-autistic people. This mistaken belief is destructive of the child’s identity and self-worth [21].

ABA teaches autistic people that their needs are less important than pleasing other people. This makes autistic children over compliant, leaving them vulnerable to manipulation and abuse. These children need to be taught how to express and get their needs met, not to be taught that their needs are less valid than the needs of people around them [21].

Conclusion: The psychology professions urgently require a causal based definition and description of autism, for which I recommend the following: [17].

Definition: Autism is perpetual and unrelenting hyperfocus, the state of intense single-minded concentration fixated on one thing at a time to the exclusion of everything else, including one’s own feelings. The probable cause of hyperfocus is a dysfunctional cingulate gyrus (CG), that part of the brain which focuses attention.

Description: Autism is an inherent neurophysiological difference in how the brain processes information. Autistic people live in a specialized inner space that is entirely intellectual, free from emotional and social distractions. They tend to observe the world in scholarly detail without feeling any emotional attachment to what they see.

References

- Blatt G. Autism, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact, Nervous Child, 1943.

- Opai K. A time and space for takiwātanga. Altogether Autism.org.nz.

- Asperger H. Autistic psychopathy in childhood. Autism and Asperger Syndrome, edited by Uta Frith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991:37-92.

- Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder. Surveillance Summaries, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dec. 3, 2021.

- Elsabbagh M, Divan G, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research 2012;5:160-79.

- Lundström S, Reichenberg A, et al. Autism phenotype versus registered diagnosis in Swedish children: prevalence trends over 10 years in general population samples. British Medical Journal 2015, Apr. 28.

- Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, et al. Diagnosis Lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum diagnosis. Autism 2016;(7):783-95.

- Rodgaard E, Jensen K, et al. Temporal changes in effect sizes of studies comparing individuals with and without autism: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019; 76:1124-1132.

- Are We Overdiagnosing Autism. com.

- Parishak NN, Swanup V, et al. Genome-wide changes in IncRNA, splicing, and regional gene expression patterns in autism. Nature 2016; 540:423-427.

- Rylaarsdam L, Guemez-Gamboa S. Genetic causes and modifiers of autism spectrum disorder. Front Cell Neurosci 2019;(13):385.

- Grove J, Ripke S, Bǿrglum AD. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet 2019;(2):431-444.

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). APA Dictionary of Psychology.

- Rowland, D. Differential diagnosis of autism: A causal analysis. Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology 2019;(11):1-2.

- Rowland D. The neurophysiological cause of autism. Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology 2020;11:001-004.

- Rowland D. Redefining autism. Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2020;(02).

- Rowland D. Autism’s true nature. Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2021;(2).

- Rowland D. How the autistic mind functions – an insider’s report. Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2020(03).

- Rowland D. Autism as an intellectual lens. Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2020;(01).

- Rebelling against a culture that values assimilation over individuality. Neurodivergent Rebel.com.

- Basu S, Parry P. The autism spectrum disorder ‘epidemic’: Need for biopsychosocial formulation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2013;47:1116-8.