Publication Information

ISSN: 2641-6859

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2018

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Effects of an IPA Motor Activity Program on the Social Skills and Attitudes of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Tunisia

Kacem Nejah1*, Naffeti Chokri2, Elloumi Ali3

1Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Sfax, SFAX, Tunisia

2Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Sfax, Tunisia.

3Faculty of Human and Social Science of Sfax, Tunisia

Received Date: March 15, 2021; Accepted Date: April 01, 2021; Published Date: April 15, 2021

*Corresponding author: Kacem Nejah, Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Sfax; SFAX, Tunisia. Email: Kacemnejah@gmail.com

Citation: Nejah K, Chokri N, Ali E (2021) Effects of an IPA motor activity program on the social skills and attitudes of students with autism spectrum disorders in Tunisia. Adv Ortho and Sprts Med: AOASM-138.

DOI: 10.37722/AOASM.2021102

Abstract

The aim of this study is to determine the effects of a motor activity program (IPA) on the social skills and attitudes of students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Tunisia. The study sample consisted of 24 students between the ages of 6 and 12. The students were divided into two groups: a training group of 12 students (n-12 with ASD) and a control group of developing controls usually consisting of 12 students (n-12 TD). In conclusion, the program (IPA) has increased the motor and social skills of students with ASD in Tunisia and improved their motor skills.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder; Attitude; Development controls usually; Motor activity; Motor skills; Social skills

Introduction

Currently, the various theories about the autistic child allow the child to be taken into account in its entirety and to be based on the specificity of his autism, his family and his environment. These different theories guide us to deepen our understanding of the world of autism. In our work with the child with autism, as a subject. We need to think and define a specific project for each child, which includes exchange, communication, education and socialization in which schooling is provided when the child can access it. Autism is a major disorder of the social relationship and the integration of different theoretical and clinical fields is a source of enrichment in the face of the specificity of these disorders. Depending on our motor skills center practices, we refer more to certain theories that we will each develop. The psychoanalytic approach to autism. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is an analysis of a behavior characterized by social communication difficulties the behavior of the autistic shows a disorder altering social interactions and communication as well as delayed verbal and non-verbal communication abilities with an atypical evolution of communication development and language skills. Motor failure is not part of the diagnosis of ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder), but 79-83% of children with ASD do not have appropriate motor skills in their age group [1, 2]. Children with ASD, compared to the usual developing controls (TD), have a variety of poor motor skills [3]. Children with ASD may have difficulty performing age-appropriate motor skills, postural impairment, and motor planning and coordination [4]. The participation of children with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) in motor activities (AIPs) facilitates the application of activities [5], values social, medical development and the development of motor skills [6 7] of these children. Developing the skills of children with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) in communication and interaction with motor skills [8, 9]. Show that the low social abilities of people with ASD were also found to be lower in the deficits. Participation in motor activity, which is an effective tool in the development of communication and social interaction. According to the National Autism Centre (2015), IPA is a method that is used not only to improve the physical adequacy of students with ASD, but to decrease inappropriate behaviors such as anger and self-harm and to increase behaviors that are encouraged such as giving appropriate responses and taking responsibility. However, participate in physical activities, games or re-enactment activities with their peer’s children with ASD are not able to do so at the expected levels due to their communication and social interaction [10]. The development of social relations is also a defining feature of ASD. The social skills of people with ASD may be due to their inability to learn skills or lack of motivation [11]. In addition, the difficulties faced by people with ASD are mainly related to a lack of understanding of the behavior of others, such as the inability to interpret and respond to social and emotional signals given by others, including eye contact and facial expressions (Sowa to examine positive and negative peer attitudes towards inclusive physical education [12]. In the review of the literature on children with ASD, no research was found in which social skills, motor skills 2012). Studies have shown that problematic behaviors related to social communication deficits in children with ASD and that the communication and interaction skills of children with ASD improved when they participated in the IPA [13, 14]. Behavioral problems also limit the ability of ASD students to acquire social, communication and academic skills by preventing them from joining learning activities and social interactions [15]. This can lead to a negative attitude towards people with ASD in physical education teachers and peers. An attitude study conducted on adapted physical education is the assessment of peer thoughts, feelings and beliefs about participation and inclusive practices [16]. Some studies in this area have shown that the general attitude to disability and inclusion issues is positive, while some have shown ineffective and negative results. These conflicting results suggest that more research is needed in this area. It is therefore important and peer attitudes were analyzed together. The overall objective of this study was to study the effects of an IPA program on motor skills, social skills and social attitudes and attitudes of students with autism spectrum disorders in Tunisia

Methodology

Participants

As part of this study, students from autism center education to the Sfax region of Tunisia have moved from this experience. In this school, ASD students were trained in special education classes, while TD students were educated in separate classes at the same school. In total, the school had 22 ASD students and 35 TD students. After establishing the number of ASD and TD students, permission from parents and the School Directorate was provided for permission to communicate with educators and to discuss study planning. As a result, meetings were held with the principal of the school, special education teachers and teachers in the TD classroom to determine the participating students. After determining the number of ASD and TD students for the study sample, the criteria for inclusion and exclusion were clarified. The inclusion criteria for students were: being between 6 and 12 years of age, not attending the IPA before, having no health problems prior to the start of IPA program activities, being officially diagnosed with a low level of ASD (ASD students), not having a second disorder such as visual and hearing impairments for students with ASD. The exclusion criteria for students followed: not having attended four or more IPA programs, having a health problem during the 12-week IPA program. The 12 students with ASD were included in the study because they met the participation criteria. Of the 58 TD students who met the inclusion criteria, 12 students were determined by the simple randomization method.

Procedures

The first step in the study was to review student health reports by having separate meetings with parents and teachers of students with ASD. This evaluation stage provided a general overview of the ASD students participating in the study. The next step was intended as an adoption step for ASD students, in particular, and other participants. In this context, various applications have been made to familiarize ASD and TD students with teachers and their teaching environments. The physical education teacher belongs to the school’s faculty, which has facilitated a better understanding of the environment and the specifics of the practitioners before the start of the IPA program. In addition, to better adapt as TSA students to the environment in which the API was to be held, they were given two seasons of IPA in a separate environment (without TD peers). After these sessions, students with ASD started the IPA program with their TD peers. To enable ASD students and their peers to benefit more from the IPA program, the courses were organized individually, in groups of three or four, taking into account issues such as the size of the car activity room, the number of volunteer physical education teachers and the weekly schedules of all participating students (12 ASD students and 12 TD students). Prior to the IPA program, TD students received peer instruction in two separate 30-minute sessions on disability and ASD. During these sessions, visual presentations were made and information on the general characteristics of individuals with special needs, particularly with a focus on issues that need to be considered when communicating with students with MSD, was provided. At the end of these sessions, a question-and-answer session was held with the students.

Inclusive Physical Activity Principles

The IPA program was designed to improve the FMS for students in ASD and TD. The program was applied for 1 hour a day, 2 days a week for 12 weeks. The IPA program has been the framework for physical and motor skills development, perceptual motor development and mobility skills, namely locomotors skills. At the end of each session, a general evaluation was conducted to assess the effectiveness of the session and the principles of the next session were determined. The IPA program used the collaborative learning approach as a teaching method to increase contact and social interaction between students with ASD and their peers. To ensure that students with ASD could benefit more from the IPA program, peer-support learning activities were also used.

The IPA program activities were implemented in four stages, which were similar to the preparation of the preschool physical education activity plan. These steps were also: (1) immersive movements (5 min), (2) functional exercises (10 min), (3) group activities (35 min), and (4) whole group activities (10 min). The first step consisted of warm-up movements, including enjoyable activities with different levels of walking, running and jumping. The second step was to move the joints of the body, strengthen the muscles and the flexibility to prepare the body for the activities of the group. In the third stage, the development of FMS was supported by activities involving mattresses, ropes, balls, hoops, etc. In the last stage, games were held in which all the students participated. Throughout the four stages, special attention has been paid to physical contact between students (17).

Search Model

This study used the mixed sequential exploratory design, which consisted of two stages: the quantitative and qualitative [18, 19]. The effect of the IPA program on FMS and the social skills of students with ASD and changes in FMS and attitudes of TD peers towards students with ASD were measured in the quantitative phase. In addition, a focus group interview design was used to determine the views of teachers, peers and parents of special education students to obtain more detailed information on the effects of the IPA program on ASD and TD peers. Individual interviews were conducted with volunteer physical education teachers, who conducted the 12-week IPA program.

Semi-structured Interviews

In this study, focus groups and one-on-one interviews were conducted using a semi-structured technical interview. To this end, the interview forms were prepared to explain and support the quantitative results. These questions were then finalized by consulting the opinions of four academics, who had previous experience in the field. Focus groups and one-on-one interviews were conducted with parents, special education teachers, volunteer physical education teachers and TD peers of ASD students in a calm and appropriate environment provided by the school administration. Interviews were recorded on audio and video by a researcher, who was a knowledgeable expert who was familiar with the entire research process. The full approval of all participants was obtained with forms.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis of the quantitative stage of the data was conducted using the SPSS. The analysis of the data conducted with the Mann Whitney U trial and the Wil-Coxon grading test was designed to determine the statistically significant differences between the TGMD-3, FAS and ACL test scores obtained before and after the 12-week IPA program. The Mann Whitney U test was used to compare data between FIT and CG, while Wilcoxon’s grading test was used to evaluate data for the CG and FIT groups separately. For the qualitative stage of the data, descriptive and content analysis techniques were used. To this end, first, the recordings of the interview were transcribed and all interviewees were given code names. Then the texts were read line by line, the coding was done and the themes were created. In the final step, the data was interpreted. In interpreting the data, the descriptive narrative was applied to the feelings and thoughts of the participants by giving direct quotations in this study. Overall, this qualitative analysis of the data was followed by a review of the research objective throughout the process

Results

The sample of this study included a total of 12 ASD (8 boys and 4 girls) and TD (9 boys and 3 girls). Students who participated in the study were divided into two groups, TRG and CG Ahmet Sansi (2020), using the simple randomization method of the Office Excel 2017 program. The FIT consisted of 12 ASD students (8 boys and 4 girls) and 12 TD students (9 boys and 3 girls). It should be noted that all participants continued their daily educational activities throughout the study. In addition to their routine daily education, ASD and TD students regularly attended the API program for 1 hour, 2 days a week for 12 weeks. The study provided detailed information on the parents of FIT ASD students, physical education teachers and volunteer physical education teachers (Tables 1, and 2).

Table 1 Description of parents of students with TSA:

Code Name

Age

Gender

Education

Occupation

1 A

37

M

Secondary School

Self-Employed

2 B

37

F

High School

House Wife

3 C

32

F

High School

Self-Employed

4 D

42

F

Primary School

House Wife

5 E

35

M

Primary School

Self-Employed

6 F

39

M

High School

Doctor

7 G

34

F

Primary School

Self-Employed

8 H

43

F

Undergraduate

House Wife

9 I

48

F

High School

House Wife

10 J

34,7

M

High School

Teacher

Table 1: Two parents of the ASD students did not respond to the study invitation. Thus, they were excluded from the study. Ten parents of ASD students were included in focus group interviews because students did not participate in the IPA program. As a result, focus group interviews were conducted with parents of 10 students. The age of the participant’s parents ranged from 28 to 46 years. It was determined that most of the participating parents were housewives and that their level of education was in primary school.

Code Name

Age

Gender

Education

1

A

25

F

High School

2

B

27

F

High School

Special education teachers who participated in the discussions of the Table 2 focus groups. A special education teacher was assigned for each of the two groups because it was the code of conduct for ASD students in special education classes. As a result, two special education teachers for the 10 ASD students were included in this study. The age of special education teachers, most of whom were women, ranged from 24 to 29.

Information from volunteer physical education teachers, who participated in one-on-one interviews, was reviewed and, as a result, two volunteer physical education teachers were identified for the study. These teachers were 25 and 27 years old, women and had a graduate degree.

Changes in fundamental movement skills for ASD and TD students In this study, no statistically significant differences were determined in running, galloping, jumping, jumping, horizontal jumping and sliding locomotors skills or in two-handed striking, one-handed hitting, dribbling, catching, kicking, throwing overs treatable and sneaky throwing skills between the TSA and TD prior to the IPA program (p >.05). This showed that students in ASD and TD had similar FMS (Table 3).

Changes in the fundamental movement skills of TSA and TD students:

Somme des carrés

ddl

Carré moyen

F

Sig.

Run

TSA

10,153

23

0,441

3,531

0,4

TD

0,125

1

0,125

Hop

TSA

4,684

22

0,213

.

.

TD

0

1

0

Horizontal Jump

TSA

9,097

23

0,396

1,139

0,641

TD

0,347

1

0,347

Gallop

TSA

30,704

23

1,335

96,117

0,08

TD

0,014

1

0,014

Skip

TSA

4,971

23

0,216

6,917

0,293

TD

0,031

1

0,031

Slide

TSA

5,93

23

0,258

3,667

0,393

TD

0,07

1

0,07

Two-hand strike

TSA

10,435

23

0,454

3,63

0,395

TD

0,125

1

0,125

One-hand strike

TSA

8,486

23

0,369

2,952

0,434

Dribble

TD

0,125

1

0,125

Catch

TSA

12,042

23

0,524

37,696

0,128

TD

0,014

1

0,014

Overhand throw

TSA

5,896

23

0,256

1,153

0,639

TD

0,222

1

0,222

Underhand throw

TSA

6,427

23

0,279

1,257

0,618

TD

0,222

1

0,222

Ball skills

TSA

4,971

23

0,216

6,917

0,293

TD

0,031

1

0,031

There was a statistically significant difference in the running proficiency of ASD students in the FIT and GC after the end of the IPA program (p – 0.003) (Table 4).

Changes in the fundamental movement skills of TSA and TD students:

Run

12.88

6.61

.003*

Gallop

12.27

10.39

.002*

Hop

12.15

10.56

.008*

Skip

12.04

10.67

.000*

Horizontal

11.35

11.72

.101

Slide

10.54

11.50

.010*

Locomotor

10.35

9.56

.000*

Two-hand strike

10.08

10.61

.000*

One-hand strike

12.88

9.50

.000*

Dribble

11.35

11.72

.025*

Catch

10.73

12.61

.001*

Kick

11.88

10.94

.004*

Overhand throw

12.00

10.78

.000*

Underhand

12.35

10.28

.001*

Ball skills

11.46

11.56

.000*

Based on the results of Wilcoxon’s pre- and post-IPA signed classification tests, there was a statistically significant difference in favor of post-program musculoskeletal skills for students with ASD to (p -0.003). A statistically significant increase in the under-tests of race (p – 0.007), gallop (p – 0.027) and jump (p – 0.046). However, there was no significant difference in jump, horizontal jump and sliding sub-tests (p > .05). Based on pre-test and post-test data for ASD students, there was no statistically significant difference in the locomotors competency tests and the total test at the end of the 12-week IPA program (p > .05) (Figure 1). A statistically significant difference was found in the ball skills of students with ASD to (p – 0.004). When ball skills were studied in detail, a statistically significant difference was found in favor of the two-handed strike at (p-0.007) and kicking skills at (p-.020). On the other hand, there was no significant difference for hitting with one hand, dribbling, catching, throwing over hands and throwing skills at (p > .05). The same analysis was performed for TD students’ ball skills with pre-test and post-test data. This analysis showed that there was no statistically significant difference in ball proficiency tests or in total test results at the end of the 12-week IPA program (p > .05) (Figure 1). A statistically significant difference was found in favor of post-test locomotor skills of ASD students at (p-0.001). In addition, a statistically significant difference was found in the race (p – 0.012), gallop (p – 0.003), jump (p – 0.001) and slide (p – 0.016) skills. No statistically significant differences were determined for jumping skills (p > .05). On the other hand, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference in the locomotors skills and under-tests of TD students at (p > .05) (Table 5). A statistically significant difference was determined in the ball skills of TD students who participated in the study (p – 0.001). In addition, the statistical values showed meaning in favor of two-handed hitting (p – 0.001), one-handed hitting (p -0.012), dribbling (p – 0.003), taking (p – 0.099), kicking (p – 0,,02), overhanging throwing (p -0.01) and sneaky throwing skills (p-0.001) after the IPA program (p < .05). When the ball skills of TD students who did not participate in the API were examined, it was determined that there were no statistically significant differences in any of the skills (p > .05) (Table 4). It was deterred that this situation had not changed at the end of the IPY program After the 12-week API program, it was observed that there was no statistically significant increase in FAS (p – 0.124 in FIT; p – 0.677 in CG) and ACL (p – 0.361 in FIT; p – 0.362 in CG) of student Td scores in FIT and CG (Table 4).

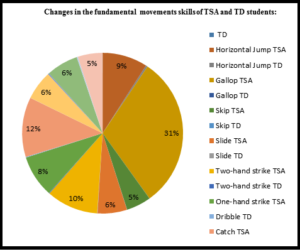

Figure 1: Changes in the fundamental movement skills of TSA and TD students.

TD Peer Perceptions of TSA Students

Based on the analysis of the qualitative data, it was determined that at the beginning of the IPA program, TD peers were afraid and shy towards their peers with ASD, but were later able to communicate better with them and were not afraid. SOFIAN, an 11-year-old student, spoke of a child with special needs, saying, “I was afraid of him. He’s got messy behaviors and he’s not following the guidelines I’m afraid. He later said that all his friends used to be afraid of their peers with TSA. Similarly, Ayman said: “The change in my attitude towards my TSA peers. At first, I was afraid of them, but now I’m not and I don’t feel shy towards them either. I can’t wait to spend my time with them. I was afraid of them before and I didn’t want them near me, but now I want to be with them

The social skills of students with ASD at the beginning of the IPA program, no statistically significant differences were determined between the social skills of students with ASD with the Mann Whitney U test. This showed that students with ASD had similar levels of social skills at the beginning of the study. The Mann Whitney U test found no statistically significant differences in the social skills of students with ASD at the end of the IPY program. According to Wilcoxon’s signed grading test conducted before and after the API program, there was no statistically significant difference in the results obtained from the SSRS-PF scale of students with ASD to (p > .05). The qualitative data obtained from the study showed that there was a positive change in the social skills of ASD students. Changes in the social skills of ASD students determined from interviews with teachers and parents.

Discussion

This study determined that the 12-week IPA program had a positive effect on MFS for ASD and TD students this finding was also supported by the qualitative data from the study.

The positive effects of physical activity on the motor skills of people with ASD [7, 10, 20-23]. Determines that physical activity varied with TD peers and that individuals with special needs do not affect the motor skills of TD peers. In fact, when conducted together, physical activities have been found to improve the motor skills of people with special needs and peers in TD [7, 14, 24, 25]. This work expands to treat psychomotor development as a result of interaction between different fields: motor skills, sensoriality, imitation, executive functions. These interactions are influenced by the environment in which the individual lives. The development of psychomotor functions may be impaired by the existence of a psychomotor disorder determined by the presence of perceptivo-motor disorders, mild neurological signs and psycho-affective disorders. But this developmental deficit can also be caused by the presence of social disorders (at the level of non-verbal communication, and at the emotional level). the hypothesis that these motor manifestations would discriminate against children with autism from other children with typical development :p ar their overall motor and fine motor skills [26], the presence of stereotyping, abnormalities of body contact, tonic peculiarities, associated with difficulties in the face of novelty and frustration [27] is the beginning of a new direction of research.

In ASD psychomotor disorders can either be included in symptomatology or independent (no link between psychomotor disorders and autism): Motor abnormalities appear very early, for some authors they even precede the onset of the characteristic symptoms of autism [28]. Motor deficits would explain, following a cascading effect, a deficit of imitation, which would have a deleterious effect on the development of the child’s social communication. Motor abnormalities are the first signs of autistic symptomatology [29]. Motor acquisitions are done on time; they are implemented in an unusual way. In fact, there are deficits in the anticipated postural adjustments and parachute reactions, and we observe that the child moves his body in bulk, especially during reversals [29]. This could be explained by a deficit in the evolution of infant reflexes a desynchronization persists in movements, it is visible in the crawler and the first steps [30].There is an asymmetry in the use of upper limbs during walking development [30-33].

Conclusion

This study concluded that the 12 week IPA program was an effective method to improve the social skills and MS of students with ASD. In addition, the results showed that it was an effective method of developing MFS among TD peers and creating positive changes in their attitudes.

For future studies, interventions can be adapted to increase the participation of people with ASD in physical activities and to encourage families to participate in these practices. Therefore, future studies should study how the daily levels of physical activity of people with ASD who participate in API programs with their parents are affected. The study also recommends examining the effects of an API program on the academic skills and fitness levels of students with ASD and ASD of different age groups. In addition, the results of this study should be compared with those of students with medium and heavy levels of ASD.

References

- Green, Craig MC (2009) Motor Skills in Children Aged 7–10 Years, Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 42:1799-1809.

- Hilton CL, Cumpata K, Klohr C, Gaetke S, Artner A, et al. (2012) Effects of Exergaming on Executive Function and Motor Skills in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Am J Occup Ther 68: 57-65.

- Frigaux A, Evrard R, Lighezzolo-Alnot J (2020) The relevance of the Rorschach test to the diagnostic evaluation of autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Evolution 85: Pages 133-154.

- Shillingsburg et al., (2015) Teaching children with autism to mand for social information.

- Ward and Ayvazo (2006) Motor proficiency and physical fitness in adolescent males with and without autism spectrum disorders

- Hutzler Margalit, Pan (2006) Effects of an Inclusive Physical Activity Program on the Motor Skills, Social Skills and Attitudes of Students with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10803-020-04693-z

- Pan CY (2011) The efficacy of an aquatic program on physical fitness and aquatic skills in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. 5: 657-665.

- Bhat AN, Srinivasan SM, Kaur M (2011) Comparing motor performance, praxis, coordination, and interpersonal synchrony between children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Res Dev Disabil 72: 79-95.

- MacDonald M, Lord C, Ulrich D (2013) The relationship of motor skills and adaptive behavior skills in young children with autism spectrum disorders Res Autism Spectr Disord. 7: 1383-1390.

- Yanardag M, Kurnaz E (2013) The Effectiveness of Video Self-Modeling in Teaching Active Video Game Skills to Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil 30: 455–469.

- Sivaraman M, Fahmie TA (2018) Using common interests to increase socialization between children with autism and their peers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 51: 1-8.

- Kim SK, McKay D, May JE, Wood J, Storch EA, et al., (2015) Assessing treatment efficacy by examining relationships between age groups of children with autism spectrum disorder and clinical anxiety symptoms: Prediction by correspondence analysis. J Affect Disord 265: 645-650.

- Frazee LIB, Taylor R, Garland AF (2003) Characterizing Community-Based Mental Health Services for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Disruptive Behavior Problems. J Autism Dev Disord 40: 1188-1201.

- Chu CH, Pan CY (2012) The effect of peer- and sibling-assisted aquatic program on interaction behaviors and aquatic skills of children with autism spectrum disorders and their peers/siblings. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 6: 1211-1223.

- Sperry L, Neitzel J, Engelhardt-Wells K (2010) Peer-Mediated Instruction and Intervention Strategies for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism Spectrum Disorders 54: 256-264.

- Hutzler Y, Margalit M (2009) Skill acquisition in students with and without Pervasive Developmental Disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 3: 685-694.

- Ozer H, Korkut E, Tulumbac F (2014) Comparative Evaluation of Oral Health Status in Healthy Children and Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 15: 223-227.

- Cheung PPP, Brown T, Yu ML, Siu AMH (2020) The Effectiveness of a School-Based Social Cognitive Intervention on the Social Participation of Chinese Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020 Sep 3. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04683-1.

- Tashakkori and Teddlie (2010) A spectrum of support: current and best practices for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) at community colleges

- DeBolt MC, Rhemtulla M, Oakes LM (2010) Robust data and power in infant research: A case study of the effect of number of infants and number of trials in visual preference procedures. 25: 393-419.

- Velkova (2010) Teaching small talk for interaction. Theoretical models http://eprints.nbu.bg/907/

- Rogers and Benetto (2002) Le fonctionnement moteur dans le cas d’autisme https://www.cairn.info/revue-enfance1-2002-1-page-63.htm

- Satterstrom FK, Walters RK, Singh T, Wigdor EM, Lescai F, et al. (2019) Autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have a similar burden of rare protein-truncating variants. Nat Neurosci 22: 1961-1965.

- Wilson CH, Dunn JM, Mars HVD, McCubbin J (1997) The Effect of Peer Tutors on Motor Performance in Integrated Physical Education Classes. In Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 14: 298-313.

- Hutzler (2003) The Role Of Physical Education For Children With Special Needs: A Review Study

- Landa and Garett-Mayer, 2010 The Joint Engagement Skills of Children at Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- Malvy J, Roux S, Zakian A, Debuly S, Sauvage D, et al, (1999) A Brief Clinical Scale for the Early Evaluation of Imitation Disorders in Autism. 3: 357-369.

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, et al. (2010) Randomized, Controlled Trial of an Intervention for Toddlers with Autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics 125: 17-23.

- Teitelbaum P, Teitelbaum O, Nye J, Fryman J, Maurer RG (1998) Movement analysis in infancy may be useful for early diagnosis of autism. 95: 13982-13987.

- Esposito G, Venuti P (2008) Analysis of Toddlers’ Gait after Six Months of Independent Walking to Identify Autism: A Preliminary Study. Percept Mot Skills 106: 259-269.

- Pan CY, Tsai CL, Hsieh KW (2011) Physical Activity Correlates for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Middle School Physical Education. Res Q Exerc Sport 82: 491-498.

- Konukman F, Yilmaz I, Yanardag M, Yu JH (2017) Teaching Sport Skills to Children with Autism Volume 88, 2017 – Issue 1

- Sowa M, Meulenbroek R (2012) Effects of physical exercise on Autism Spectrum Disorders: A meta-analysis. 6: 46-57.