Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

“Douyin” And Fake News: A Study on The Impact on Users’ Perception in The Post-Truth Era

Zhou Chenyan*

Department of Journalism, Faculty of Communication, Xiamen University Malaysia, Malaysia; JRN2209442@xmu.edu.my

Received Date: November 28, 2024; Accepted Date: December 04, 2024; Published Date: December 22, 2024;

*Corresponding author: Zhou Chenyan, Department of Journalism, Faculty of Communication, Xiamen University Malaysia, Malaysia; Email: JRN2209442@xmu.edu.my

Citation: Chenyan Z (2024); “Douyin” And Fake News: A Study on The Impact on Users’ Perception in The Post-Truth Era; Advances in Public Health, Community and Tropical Medicine; MCADD-116

DOI: 10.37722/APHCTM.2024205

Abstract

Since there has been news, there have been lies masquerading as news. In the post-truth era, fake news has become a pressing issue with the development of social media in China. However, research on the motivators and impacts of the proliferation of fake news on short video platforms is limited. The main objective of this qualitative study was to identify the reason why social media users tend to believe in fake news, as well as the impact of fake news on social media users’ perception with the lens of media dependency theory. By using the popular short video platform Douyin as a source, 340 user comments were selected based on the number of likes and analysed through in-depth content analysis. The analysis revealed the reasons that users believe in fake news on Douyin. First, the induction of user cognitive biases and herd behaviour. Second, the rendering of Douyin media ecology and social trust crisis context. At the same time, the analysis identified the impact of fake news on Douyin users’ perception. First, users were directly exposed to significant emotional and psychological manipulation. Second, users misinterpret the information while deepening the cycle of distrust towards the institutions involved. Finally, it leads to changes in the user’s behaviour. The findings suggest that short video platforms should be aware of the spread of fake news and take measures to protect their users from the effects of fake news. Furthermore, the journalism industry should think about ways to combat fake news according to the characteristics of the new media, and restore users’ confidence in the journalism industry in China.

Keywords: China, fake news, media dependency theory, post-truth, social media (Douyin)

Chapter 1

Introduction

Background

The development of social media makes it easy for people to connect and communicate with each other, but its widespread use has also led to a series of undesirable consequences. The spread of fake news on social media is one of them. Nowadays, people are in the midst of confusion brought on by the post-truth era. Facts collapse, and truths covered by emotion allow fake news to go viral fast with the characteristics of social media. It is increasingly easy for people to be attracted to and believe in fake news. Fake news on social media has become a significant challenge in the post-truth era.

Fake News in the Post-Truth Era

In 2016, the United States presidential election, which diverged significantly from the mainstream media’s predictions, brought the term ‘post-truth’ to public attention (Bluemle, 2018). In the same year, the Vote Leave organisation’s potentially misleading use of one-sided data during the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom also caused a public debate about the term ‘post-truth’ (Marshall, 2020).

As a result, the term ‘post-truth’ has gained popularity among the general public in the form of ‘post-truth politics,’ and its usage has surged. Oxford Dictionaries named post truth as Word of the Year for 2016 as searches for it on Google increased by more than 2,000% over the previous year (Flood, 2016). Initially proposed as a political concept, post-truth has gradually expanded into more diverse fields of study, such as education, anthropology, communication, etc.

“Is Truth Dead?” was the question Time magazine posed on its 3 April 2017 cover. Today, in this post-truth era where suspicion and uncertainty abound, this question remains thought-provoking. In the post-truth era, truth is not dead. Truth still exists objectively, unquestioned and unmodified; it has simply become unimportant. Opinions over truth and emotions over facts have become unavoidable problems in the post-truth era.

Since there has been news, there have been lies masquerading as news. The 2016 U.S. presidential election not only awakened the public to post-truth, but it also brought fake news, especially fake news on social media, to the spotlight. After the election, which was dominated by allegations of fake news, the Collins Dictionary named fake news as Word of the Year for 2017, as it showed a 365% increase in usage over the previous year (Sauer, 2017).

Fake news is one of the most popular subcategories under the wide range of issues in the post-truth era (Neupane, 2020). The post-truth era has created a journalistic environment where personal beliefs, emotions, and biases precede objective reporting and fact-checking. Objective news is disregarded and gradually shifted towards subjectivity, and journalistic norms corrupted by post-truth create fertile ground for disinformation and polarised narratives (Gbenga et al., 2023). The proliferation of fake news under the cover of post-truth characteristics has become difficult to recognise as an intractable pretender.

Fake News on Social Media

Fake news is not a new concept, but the participation of social media has amplified its dangers, allowing fake news to affect almost everyone through social networking.

The definition of social media has evolved over time. In the early stages, the definition of social media focused on people and socialising, while later on, the generation and sharing of content (Aichner et al., 2021). In the new media age, where everyone can easily have a social media account, the one-way communication method used by professional news media to deliver news to the public has been broken. Every social media user can be a news publisher and disseminator, regardless of whether they are educated in professional journalism or whether they can judge the credibility of information. Social media has made the news world extremely democratised (Rhodes, 2021).

However, social media cannot play the role of a social watchdog or complete the responsibility of a gatekeeper, and the vast amount of information within it cannot be guaranteed to be accurate, balanced, and credible (Neupane, 2020). The structures and strategies of social media companies to drive the scale of the big data surge provide a favourable environment for the spread of fake news. Fake news spreads more rapidly than other content on social media (Olan et al., 2022). The prevalence of fake news caused by the development of social media has become a significant feature of the post-truth era (Muqsith & Pratomo, 2021).

Douyin and Fake News

The post-truth culture, co-facilitated by the global media, is not just happening in the Western world. In China, the spread of fake news on social media in the post-truth era is also becoming increasingly apparent.

As one of the most popular Chinese social media platforms, Douyin had more than 600 million monthly active users in 2022. Douyin’s operation model is basically the same as its international version Tik Tok. Its content production model is user-generated, encouraging users to create content through short videos. The platform operator is responsible for the management and promotion of the platform.

Douyin users are mainly divided into two categories: content creators and content consumers. The former is mainly responsible for producing short videos to achieve self-disclosure or economic benefits; the latter is mainly for leisure and entertainment and gives feedback to the former, such as following, liking, favouriting, sharing and so on. As the most active social media platform, Douyin is not only a centre for information exchange but has also become a gathering place for fake news.

Problem Statement

The development of communication technology has reshaped how information is disseminated in modern society, and new media have conveniently facilitated the dissemination of information by providing users with a free communication platform (Wu, 2020). In China today, the pervasive Internet and social media have become powerful forces of change, allowing ordinary people to easily share their views and information (DeLisle et al., 2016). By January 2023, China’s internet penetration rate reached 73.7%, and the number of social media users reached 1.03 billion, accounting for 72% of the total population (Kemp, 2023). Among them, 10.26 billion users have accounts on short video platforms (CNNIC, 2023). Douyin (TikTok) has stood out from the crowd of short video platforms and has become an explosive short video platform in China and even the world.

However, the development of social media has also brought instability to the online environment. The characteristics of real-time interaction, user-generated content, mass communication and anonymity make it challenging to manage public opinion on social media (Carr & Hayes, 2015). Nowadays, social media has become a powerful source for the spread of fake news. The development of social media has made it easier for fake news to be created as well as more difficult to detect, thus significantly affecting society (Aïmeur et al., 2023). The proliferation of fake news on social media is pronounced in China. A study on fake news in China found that more than half of respondents admitted to having encountered or shared fake news on social media, and more than 70% believed that fake news was harmful to society (Tang et al., 2021). Another study showed that fake news was perceived as a widespread social problem in China, and people were often exposed to it and confused by it (Willnat et al., 2018).

In March 2024, the sensation caused by the fake news ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ on Douyin is a typical example. On March 15, 2024, ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ suddenly became a hot search term on Douyin platform. Yingxiaohao who published ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ claimed that starchy sausage was exposed as having quality problems in the 3.15 Gala, and that its ingredient list contained bone paste, which is not recommended for human consumption.

Within a short period of time, a large number of Yingxiaohao produced videos with this topic for dissemination. As one of the most common and favourite snacks in life, the news of ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ caused extensive discussion among users. In addition to Yingxiaohao, all kinds of influencers followed this trend and released related videos to express their disappointment with starchy sausage. Starchy sausage instantly became a threat to everyone. In the following days, the sales of starchy sausage dropped dramatically, and the chairman of starchy sausage company FUYU could even only rely on live streaming to eat starchy sausage on-site at the production factory to prove that his product was safe.

As the situation became more and more serious, some users also questioned the content spread by Yingxiaohao, such as the 3.15 Gala did not mention starchy sausage at all, and the reporter concluded that the logic of ‘bone paste is not recommended for human consumption’ is also flawed. In the midst of the user controversy, on March 19, China Food News, a professional newspaper in China’s food industry, released a video on Douyin, responding to the rumours of ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ with scientific arguments. Although Yingxiaohao still continues to spread fake news about starchy sausage, most of the public opinion has been reversed, and even in the live streaming of Douyin’s ‘Little Prince of Starchy Sausage’, its sales have increased 10 times.

The fake news of ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ had a far-reaching impact, but it was reversed in a short period of time. Similar fake news cases happened frequently on Douyin, and ‘I can’t believe Yingxiaohao/news anymore’ was once the comment of users after they realised that they had been deceived by fake news. However, every time a fake news videos occur, there are still a large number of users who believe in the fake news and spread it further. Douyin users’ reasons for believing fake news have become an urgent issue to be explored, and the impact of fake news on users is also worth noting.

Now, this phenomenon has received some attention in research. Some scholars focused on the characteristics of fake news on social media and explored new methods of fake news detection (Shu et al., 2017; Medeiros & Braga, 2020), to prevent fake news. Meanwhile, some scholars investigated the reactions and behaviours of particular groups of people when dealing with fake news, such as students (Leeder, 2019; Johnston, 2020) and the elderly (Casas et al., 2022; Luce & Estabel, 2020). However, there is still a lack of research exploring the reasons why users are likely to believe fake news from the perspective of social media users.

Some studies have explored the impact of fake news on health (Rocha et al., 2021; Zanatta et al., 2021), marketing (Mishra & Samu, 2021; Cham et al., 2023) and news media credibility (Tandoc et al., 2021). However, it is the users who are directly affected by social media fake news. As social media users who have been exposed to fake news, there is still insufficient research focusing on social media users themselves to explore the impact of fake news on users’ cognition, affect and behaviour.

Moreover, most of research on fake news focuses on social media such as Twitter and Facebook with a Western context (Bovet & Makse, 2019; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019; Chauhan et al., 2022). There is a lack of targeted research on Douyin, an emerging short-form video platform in China. Moreover, when post-truth is used as a precondition for the study of fake news, most scholars will limit it to political and democratic aspects (Farkas & Schou, 2019; Giusti & Piras, 2020), and the role of post-truth in the fields of communication and journalism has not been demonstrated. There is also insufficient exploration of social media users, as the group is directly exposed to fake news.

Based on these circumstances, this study takes Douyin in China as the research object to explore the reasons Douyin users believe in fake news and the impacts of fake news on users’ perception, to fill the current academic gap and provide a basis for future research on fake news on Douyin.

Research Questions

RQ1: What makes Douyin users believe in fake news?

RQ2: How does fake news on Douyin affects users’ perception?

Research Objectives

This study aims to record and collect video content related to fake news that has caused widespread dissemination, along with user likes, comments, and other reactions to this content on Douyin. Through in-depth content analysis, this study would investigate the motivators that make Douyin users likely to be attracted to and believe in fake news, as well as the ways this fake news affects Douyin users’ perception.

In the following research objectives and research questions, the term ‘fake news’ refers to fake news in the form of videos posted and disseminated on Douyin platform. Below are the research objectives in specific:

RO1: To identify the reason why Douyin users tend to believe in fake news.

RO2: To explore how fake news affects Douyin users’ perception.

Theoretical Framework

Media dependency theory provides a framework for understanding the complex relationship among media, audiences, and social systems (Zhang & Zhong, 2020). The classical sociological literature from Durkheim (1933) to Marx (1961) to Mead (1934) encouraged treating the media and their audiences as integral components of a vast social system, and this perspective offered an idea for the emergence of media dependence theory. Inspired by this, media dependence theory was first proposed and conceptualised by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur in 1976 in their article ‘A Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects.’ However, unlike the sociologists mentioned above, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur were more concerned with the effects of social change on the media and the resulting audience dependence on news media updates than labour and class dependence (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976).

In the model proposed by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur, the mass media as a source of information for individuals and society will influence people’s cognition, affect and behaviour, and the nature of the interdependent relationship among the three parties determines the impact that the media will have on individuals and society (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). At this stage, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) summarised people’s dependence on the media as a need for satisfying information. Specifically, these needs are the need to understand the social world, the need to act effectively, and the need to escape reality through fantasy. This is a macro level that focuses on the increased reliance on media for information in the face of social uncertainty (Ho et al., 2014).

With the iteration of media dependency theory, Ball-Rokeach (1985) replaced the term needs with goals, as goals imply motivation to solve problems based on dependency relationships. The three goals that underlie an individual’s media behaviour are understanding, orientation and play. Compared to dealing with the relationship between media and social institutions, this stage is a micro level, focusing on the relationship between media and individuals (Riffe et al., 2008). The relationship between the media and the audience is considered asymmetrical, where the mass media control the information resources and the individual user can only access the distributed resources (Ball-Rokeach, 1985). Although changes in terminology and focus have occurred, the original proposition of media dependence theory remains unchanged: the more dependent a person is on the media, the more likely they are to be influenced by it.

In terms of cognition, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) summarise five consequences of people’s dependence on the media. The first is the creation and resolution of ambiguity, which means that the media delivers and presents information through filtering, thereby limiting the audience’s ability to interpret the information. The second is attitude formation, whereby the media draws public attention to specific events by constantly flowing them, thereby creating emotions in people when confronted with this information. The third cognitive effect is agenda setting, whereby audiences allow the media to gather information with which they are familiar and later selectively expose themselves to this type of information based on personal preference (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). The fourth is the expansion of personal belief systems caused by the media through constant monitoring and presentation of societal changes. Finally, regarding values, the media has the effect of causing social value conflicts, clarifying values and defining social identity.

In terms of affect, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) argued that the media may lead to emotional effects such as desensitisation and numbness, fear and anxiety and triggered happiness, altered morale and alienation in audiences. In terms of behaviour, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) classify the effects of media into two types. The first is activation, where audiences do things they would not otherwise do as a result of receiving information from the media, and the second is de-activation, where audiences behave differently as a result of the media’s influence.

Relationships in media dependency theory are not fixed; they vary depending on media centrality and social situations (Kim, 2020). The centrality of media resources to satisfy personal goals is influenced by personal factors, and the greater the centrality of the media, the greater the dependence of the audience and society on it (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). In addition, the more pronounced the social conflict and social change, the more people rely on the media (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). At the same time, Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) point out that cognitive, affective and behavioural changes in audiences can, in turn, affect the media and society, which is a crucial difference between media dependence theory and uses and gratifications theory.

Media dependency theory is helpful in this study because it explains the dependency among the media, audience and social systems, as well as how the three influence each other. In the 21st century, with the significant development of new media, the value of media dependency theory has remained strong as the dependency relationship among media, socialisation, and audience remains important (Kim, 2020). As an emerging short-video media, users rely significantly on Douyin for information, and Douyin influences users as a result. Users’ trust in fake news and the effects it has on them is a reflection of media dependency theory. Furthermore, media dependency theory deals with the influence of mass media on audience cognition, affect and behaviour. This has some similarities to the impact of social media fake news on users’ perceptions, which this study aims to explore.

By incorporating media dependency theory and understanding the significance of the relationship between media and users in relation to Douyin fake news, this study can provide deeper research into the mechanisms of fake news dissemination on Douyin, thus analysing the factors that motivate users to believe in fake news and the impact that these fake news have on users.

Significance of Study

This study provides insight into the prevalence of fake news on Chinese social media in the post-truth era, with a particular focus on Douyin, a popular social media platform. This study contributes to an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms and impact of fake news arising on Chinese social media.

The spread of fake news in China has been increasing in severity with the growth of online media news consumption. As of June 2023, there were 781 million online news users in China, accounting for 72.4% of the total Internet user base (CNNIC, 2023). Although many Chinese scholars realise that fake news has become a significant issue in China, there is still a lack of discussion about fake news in the Chinese media (Tang et al., 2021). There are also a few papers that combine the contemporary feature of post-truth with fake news and social media in China. Meanwhile, the new development of media dependency theory in the age of social media is also noteworthy. This theory has not been researched in China in terms of related topics at present. This study supplements the above discussion by using media dependency theory to explain the phenomenon of fake news on Douyin platform and further discussing fake news in China.

Beyond the academic area, this research also provides insight into the social media industry and journalism in practice. Although China has carried out many measures to combat fake news, fake news is still commonplace on social media. This disrupts the online environment on social media and dramatically affects the journalism industry’s reputation. By investigating the facilitators of the popularity of fake news on Douyin platform and its impact on users, this study provides a reference for social media industry and journalism industry to understand the mechanism of fake news dissemination and the psychology of users, which will help the relevant industries to combat fake news more effectively. At the same time, this study offers a reference for users to understand the facilitators of users’ belief in fake news, which can help users prevent fake news in social media.

Definition of Terms

Fake news: The definition of fake news gets complicated after being associated with politics. Generally, fake news is used to represent a wide range of false or distorted information, which may be intentional or unintentional (Paor & Heravi, 2020). At the same time, fake news can masquerade as legitimate news sources, express bias or diminish the news media’s credibility (Egelhofer & Lecheler, 2019).

Post-Truth: In the post-truth era, expertise and scientific data are suspect (Buechler, 2023). The public’s opinion of the truth is based more on belief than evidence, and disregard for facts has become normal (Drexler, 2020). Individuals are biased to make judgements based on the feelings that arise from group identity (Ahlstrom, 2023).

News consumption: The emergence of the Internet has made online media a widely available source of information, and today, people are increasingly relying on the Internet as a news source (Robertson, 2023). In China, social media news consumption is growing along with social media usage (Zhou & Lu, 2023).

Yingxiaohao: Yingxiaohao are a particular category of marketing accounts formed during the development of marketing accounts in China (Li, 2023). Yingxiaohao are various types of online public accounts that use the collection and processing of specific information as a method of attracting traffic by engaging and creating public opinion and then obtaining economic profits (Liu & Wang, 2021).

Perception: Perception is the way that a person or group views a phenomenon; it involves the processing of stimuli, learning and memorising during understanding, and is subjective and specific (McDonald, 2011). In this study, perception refers to users’ cognition, affect and behaviour towards fake news.

Chapter 2

Literature review

Fake News and Post-Truth

Fake news is a phenomenon that has existed for a long time. It can be traced back to ancient Athens, where merchants brought a flood of fake news for financial gain (Lewis, 1996). While the history of fake news far predates the development of digital technology, the Internet and social media have made the definition of fake news increasingly complex.

Yerlikaya and Aslan (2020) argues that fake news is different from disinformation and misinformation. Disinformation is the unintentional provision of incorrect information, and misinformation is the intentional distortion of information. Fake news, on the other hand, is an intentional verifiable falsehood. However, Verstraete et al. (2022) classify fake news into four categories: hoax, satire, propaganda and trolling. The classification is based on two characteristics: whether the author intends to deceive and whether the intention to create and disseminate is economical.

In contrast, Muqsith and Pratomo (2021) classifies fake news into two categories based on the motivation of the fake news providers. The first is fake news that intentionally misleads readers, and the second is fake news that is created to gain clicks for financial profit. Conversely, Hainscho (2022) criticises the definition of fake news as some text with a return to truth as the solution. Hainscho (2022) points out that truth is not absent in the post-truth era but is everywhere. Fake news is the product of people stubbornly believing in their own beliefs, even if they are sometimes wrong. So, fake news should not be a symptom of post-truth but a sign of personal belief.

This chapter will summarise the definitions of fake news by scholars and define fake news as the information published or disseminated intentionally or accidentally out of any interest that is false and misleading to the audience.

Oxford Dictionary defines post-truth as ‘relating to and denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’ However, post truth is still a vague concept at present. Bufacchi (2021) argues that Oxford Dictionaries’ definition of post-truth focuses on the subjectivity of post-truth and ignores the objectivity of truth, which can be misleading. Based on this, Bufacchi (2021) defines post-truth as a deliberate strategy to cause an objective fact to have less impact in shaping public opinion, which aims to subvert one’s relationship with the truth and delegitimise it to some extent.

In contrast, Fuller (2020) states that post-truth does not deny any objective facts; it aims to diminish the distinction between fact and fiction, thus weakening the moral high ground of the truthers. According to Wahyono et al. (2020), post-truth is an era in which people communicate based on emotional considerations, where the truth is no longer important. Therefore, people are more inclined to look for justification than verification.

Factors Influencing Fake News Usage

Although the spread of fake news has become a well-known issue, people always seem to be deceived by fake news time after time. Fake news masquerades, cognitive biases, echo chambers and filter bubbles increase the possibility that people believe fake news.

The Masquerade of Fake News

Strategically presenting fake news content to achieve false legitimacy and have some features of real news is a way for fake news to earn people’s credibility (Domenico et al., 2021). Therefore, masquerading as real news is an essential method for fake news to be successful.

Domenico et al. (2021) summarise the features that fake news disguises in three points: (1) imitation of source websites, (2) elaboration of headlines and sub headlines, and (3) imitation of a text corpus. Specifically, Domenico et al. (2021) argued that starting from the name of the website, fake news websites imitate legitimate news websites. In addition, the layout and elements, such as fonts and colours, of the fake news websites are also close to those of legitimate news websites. In terms of headlines, fake news will have a journalistic writing style with sensational headlines and sub headlines to attract the audience and influence their thinking and feelings (Gu et al., 2017). In terms of text corpus, although fake news tries to mimic news from legitimate sources, there are still differences in tone and style, such as fake news more often uses expletives, pronouns, and low linguistic register to infect the readers, as well as having a more substantial positive or negative effect (Jack, 2017; Asubiaro & Rubin, 2019). These features of fake news increase the emotional appeal to readers while masquerading as real news, making readers more likely to be deceived by fake news.

In contrast to Domenico et al. (2021), Zhang and Ghorbani (2020) summarise the characteristics of fake news into three categories: large volume, wide variety and fast speed. Specifically, everyone can publish fake news through the Internet, and some websites intentionally publish false information, leading to a large amount of false content spreading on the Internet without users’ awareness. Furthermore, Zhang and Ghorbani (2020) argue that rumours, satirical news, false advertisements, and conspiracy theories are all similar definitions to fake news, and these vast varieties make fake news penetrate every aspect of people’s lives. Finally, fake news creators tend to be short-lived, and the real-time nature of fake news on social media makes identifying online news difficult (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017; Zhang & Ghorbani, 2020). These features make identifying fake news more complex as users are potentially exposed to a large amount of fake news on all fronts.

Not only the presentation and volume characteristics, fake news even mimics the news value of traditional news to some extent. Tandoc Jr. et al. (2021) found that most of the fake news on fake news websites have news values such as timeliness, negativity, and prominence. These news values not only facilitate the disguise of fake news but also the concealment of the publishers. Fake news with news value undoubtedly makes it easier for readers to believe it. In addition, some social media platforms do not differentiate the quality of information shared between users, leading users to mistakenly believe that fake news has the same quality as news from legitimate sources (Rhodes, 2021). This also blurs the audience’s perception of recognising fake news.

Besides the characteristics of fake news itself, the development of digital technology has also made fake news more deceptive. For example, deep fake in digital deception is a technique used for realistic face swapping in videos or pictures (Rana et al., 2022). Muqsith and Pratomo (2021) point out that people’s photographs, videos, and voice data are dispersed in the digital space, which can be utilised by deep fake techniques to distort the facts. These technologies provide fake news with false evidence that appears to be true, making it easier for people to believe fake news easily.

Confirmation Bias

In the post-truth era, objective facts hidden by emotions are gradually lost. Tandoc Jr. et al. (2021) found in their study that 64.3% of the 886 fake news articles included the writer’s personal views, and the lack of objectivity enabled the fake news to explicitly appeal to the readers’ existing tendencies by including their personal views. For this tendency to believe in fake news with personal views, Jia et al. (2023) used confirmation bias as an explanation.

Confirmation bias is used to express the behaviour that people tend to look for information that supports their beliefs and opinions and will, therefore, ignore flawed data (Nickerson, 1998; Myers & DeWall, 2015). Peters (2020) argues that confirmation bias leads to an unwillingness to believe in realities that are different from one’s own beliefs so that even if there is conflicting data in the information, people will ignore it because it is the same as their own opinion, which can hinder an individual’s pursuit of the truth. This is further supported by the research of Kappes et al. (2020). After examining confirmation bias when utilising the opinions of others, they found that people are less likely to change their opinions when confronted with opposing opinions. People’s confirmation bias makes them unintentionally willing to believe fake news that expresses the same opinion.

On the other hand, Mercier and Sperber (2017) argue that making one’s opinion credible and able to persuade others has become the purpose of human reasoning. Thus, the purpose of confirmation bias has become to serve persuasion. This phenomenon is reflected in fake news by focusing more on persuading readers with opinions compared to facts. This tendency of fake news makes it easier for people to be influenced emotionally and to believe in fake news.

Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles

Terren and Borge (2021) argue that the more users are exposed to social media news feeds with strong personal opinions, the more likely they are to be in the echo chambers and filter bubbles. In the post-truth era, echo chambers and filter bubbles created by fake news full of personal emotions have also become a disorientating factor for users. Cinelli et al. (2021) broadly define echo chambers as an environment in which a user’s opinions and beliefs about a specific topic are reinforced by repeated interactions with peers or sources that share the same attitudes. Eli Pariser (2011), the proponent of the filter bubble, describes it as a social media recommendation system that connects users with information similar to their perceptions and encourages them to follow content similar to the views they hold.

In the analysis of echo chambers and filter bubbles, Nguyen (2018) points out that while the concepts of the two have similarities and are often referred to at the same time, they actually work in different ways. In support of this, Terren and Borge (2021) also acknowledged the differences between echo chambers and filter bubbles. Specifically, echo chambers are the homogenisation caused by users actively interacting with people with similar views. In contrast, filter bubbles are algorithm-driven, selectively recommending similar content to users based on their past behaviour. Overall, the two differ in terms of algorithms and levels of abstraction. In contrast, Talamanca and Aefini (2022) criticised this view, arguing that in both echo chambers and filter bubbles, it is not the preference algorithm and the information itself that matters but how the user reacts and interacts with the information presented on the platform.

However, in any case, there is no doubt about the impact that echo chambers and filter bubbles have on users’ perceptions. Choi et al. (2020) identified hub rumour echo chambers in an echo chamber network and found that hub rumour echo chambers greatly impacted rumour spreading and reposting. Surrounded by similar content, users have more difficulties in finding the truth beyond perception. Fake news is more likely to go undetected with the help of echo chambers and filter bubbles.

The above literature analyses the characteristics of fake news and provides a reference for this study to investigate why users believe in fake news. However, the above literature mainly focuses on the text and picture types of fake news, and there is still a lack of the characteristics of fake news dissemination on the short video platform, which is a unique social media. This study will fill these gaps by exploring the dissemination characteristics of fake news on Douyin short video platform.

Factors Influencing Fake News Sharing

As a longstanding phenomenon, fake news has become particularly threatening in the new media era. Nowadays, the widespread dissemination of fake news has become unavoidable and worse. The changing news environment brought by the development of social media; the emotional dominance caused by the post-truth era as well as the lack of user literacy are factors that cannot be ignored.

Social Media Characteristics and the Changing News Environment

The role of the Internet and social media is particularly prominent in the vast literature studying the spread and development of fake news. In the digital age, social media can satisfy people’s diverse needs, providing users with great convenience in both communication and entertainment. However, as Muqsith and Pratomo (2021) mention, when analysing the development of fake news for information, convenience instead brings disaster. They argue that the easier it is for people to create and disseminate information, the easier it is to abandon journalistic principles. The overly fast distribution flow of social media also makes it difficult to verify the authenticity of information.

Olan et al. (2022) point out that the strategy of social media platforms is to generate news and information that attracts a large number of targeted viewers to repost it and to gain profit from the viral spread of this content. This structural feature of social media actually provides a favourable environment for the spread of infectious content such as fake news. In support of this, Gbenga et al. (2023) attribute the phenomenon of the massive spread of fake news on the Internet to its eternally connected nature and emphasis on speed over accuracy. They argue that Internet providers and distributors are using all possible means to motivate traffic to gain profit. This has led to many journalists being forced to publish articles before verifying them to capture attention.

When talking about the current social media environment, Rhodes (2021) summarises it as the drop of gatekeepers and the rise of extremely democratised news—the former points out that the current media environment lacks actors that can stop the spread of falsehoods. For example, social media such as Facebook do not differentiate between high and low-quality information, presenting fake and trustworthy news similarly, leaving users with a false impression. The latter focuses on the convenience of social media, which means that anyone can easily create one or more social accounts and post news content without any expertise or professional journalism norms.

Domenico et al. (2021) express a similar view when summarising the characteristics of communication channels. They argue that the low-barrier feature of social media greatly reduces the cost of content creation, and everyone can have a free account for content publishing. The feature of social media as a source of information has changed the process of creating and sharing information, and user-generated content can be published and shared without any editing or supervision, leading to false information spreading even faster and wider than real news. As Paor and Heravi (2020) argue, information used to be carefully controlled by media members, journalists and librarians.

In contrast, the open and ubiquitous digital environment now makes it difficult for these traditional gatekeepers to control and verify information. In addition, Zhang and Ghorbani (2020) argue that the anonymous nature of social media is also one of the reasons for the spread of disinformation, as users are not required to take responsibility for the content they post, share and comment on. Overall, social media has contributed to the spread of fake news while providing convenience to people.

The Emotionally-Driven Post-Truth Era

The rise of social media has led to widespread exposure to unfiltered and fact-checked opinions, and this increasing fragmentation of the media landscape has become one of the main reasons for the development of post-truth (Gbenga et al., 2023). According to Muqsith and Pratomo (2021), today’s society prefers facts that are in harmony with their emotions. The truth is not the main factor in making news, and emotions determine what is the truth. However, journalism cannot be separated from objectivity in pursuing truth. Putting emotions above objective facts will inevitably lead to the proliferation of fake news. Therefore, Ha et al. (2019) argue that post-truth based on the emotional market would otherwise lead to the media being polluted by issues such as fake news.

The clickbait headline is a common practice in the post-truth era, making it easier for fake news to spread. Based on social media’s own particular thin-slice format, Domenico et al. (2021) argue that headlines are created to capture users’ attention and providing a headline that influences the user’s opinion is more important than providing the source of the information. The phenomenon of blurring news facts with emotional factors is common in the post-truth era, making it more difficult for people to examine the truth or falsity of the news critically and facilitating the spread of fake news.

Emotional influence is not only reflected in the production of news content but also becomes a significant motivation for users to share news (Arikenbi et al., 2023). In a study of the sharing of fake news on social media in Nigeria, Wasserman and Madris-Morales (2018) found that people are more likely to share fake news such as entertainment, politics, and other fake news related to patriotism and emotional elements.

In addition, people would regard news sharing as an expression of civic duty and social cohesion. As Talwar et al. (2020) found in their study of motivations for sharing fake news, people may not share fake news out of malice but out of a need to keep the group informed and connected. Similarly, Olan et al. (2022) found that in terms of social acceptance, users unconsciously help spread fake news to spread alerts related to fake news events. Although users usually share news with good intentions, Ha et al. (2019) noted that people are unable to distinguish whether the information they share is true or not, so it leads to the spread of fake news.

Herd Behaviour and the Absence of User Literacy

Herd behaviour refers to the fact that people in groups tend to show similar thinking and behaviours (Shiller, 1995), with individuals reflecting a tendency to ignore their own opinions and follow the decisions of others (Sun, 2013). In social media, features such as likes and comments provided by platforms enable users to more easily observe the behaviour of others, thus deepening herd behaviour (Mattke et al., 2020). Apuke and Omar (2020) demonstrated that herd behaviour plays a significant driving role in the spread of fake news by using conceptual models to predict the factors that influence the sharing of fake news. Similarly, Pröllochs and Feuerriegel (2023) found that the spread of false rumours displayed a significant tendency to follow the herd, with the spread of false rumours surging under larger cascades. Further, Zhang et al. (2024) used model analysis to find that herd behaviour on social media significantly influences users to share unverified information. These suggest that herd behaviour increases people’s sharing of fake news.

Ruak (2023) argues that users’ awareness, attitudes and behaviours influence the dissemination of hoax news. As early as the 1990s, digital literacy was defined by the emergence of computers as the ability to understand and use various forms of information presented by computers (Gilster, 1997). However, Pangrazio et al. (2020) pointed out that with the development of digital practices, different technological, educational and political historical contexts have influenced the concept of digital literacy in different scenarios.

Wu (2024) found that although Chinese scholars are rich in digital literacy research, there is no officially published framework or standard for digital literacy, and digital literacy training is lacking. Guess et al. (2020) found that digital literacy is an effective strategy for identifying fake news by examining samples from the United States and India. However, in China, where there is a shortage of digital literacy, the ability of users to identify fake news needs to be improved, thus providing an environment for fake news to spread.

Unlike the findings of Guess et al. (2020), Jones-Jang et al. (2019), after evaluating media-related literacies such as media literacy, information literacy, and digital literacy, found that the accurate identification of fake news was most relevant to information literacy compared to other literacies. Information literacy, constructed based on the digital media environment, involves the ability to select relevant information, identify false information, verify the accuracy of the information, and present the information in its original form (Zhang & Wang, 2024). Although information literacy plays an important role in combating fake news, Jia et al. (2023) found in their investigation of fake news related to the Russian-Ukrainian war that the current information literacy of people has not been sufficiently improved to cope with the new media environment. The lack of media-related literacy becomes one of the reasons why fake news spreads more easily.

The Impact of Fake News on Perception

As a global problem, the dangers of fake news have brought widespread attention to its impact in various aspects. On social aspects, fake news can influence public opinion, incite emotions, damage reputations and even shape political decisions (Ruak, 2023).

Economically, fake news can disrupt financial markets and affect brand reputation and effectiveness (Gbenga et al., 2023). For journalism, fake news erodes the news media and robs journalism of its authority (Olaniran & Adeyemi, 2020; Domenico et al., 2021). But at its root, this series of influences of fake news stems from its impact on audience perceptions, which in this study means cognition, affect and behaviour.

The Impact of Fake News on Cognition

Cognition is the mental process of acquiring and understanding knowledge (Subedi, 2022). Regarding the impact of fake news on audience cognition, Guo et al. (2021) argues that fake news affects cognitive activities such as opinions through human content interactions. Domenico et al. (2021) suggest that fake news can change consumer cognition and attitudes towards brands and products, and brands affected by fake news may face reputational damage or product boycotts. To further explain, Sharif et al. (2021) stated that false information about a brand can alter consumer cognition and lead to negative associations with the brand; while Mariconda et al. (2024), through three experiments, found that fake news can have a greater impact on consumers’ reputational assessment of an organization. That means, fake news can influence the audience’s opinion about an object, change the audience’s cognition and even behavioural intention

In addition to this, Ladeira et al. (2022) used eye-tracking techniques to demonstrate that viewers gaze at fake news more often and longer than real news. That is, fake news increased the cognitive processing of the viewers. Similarly, Qiu et al. (2017) showed that information overload and limited attention due to fake news reduced people’s ability to recognize fake news. Besides that, Mansur et al. (2021) found that understanding hoax news, fake news, etc. effectively contributes to cognitive ability as high as 32.4% through a quantitative survey of adolescents aged 15-18 years old. In other words, the higher the level of understanding of fake news, the lower the cognitive ability of adolescents. While Keersmaecker and Roets (2017) have pointed out that for people with low cognitive ability, even pointing out that the information is wrong cannot completely eliminate the effect of the initial misinformation. Thus, it is clear that the impact of fake news on the audience’s cognition makes it more difficult for them to distinguish fake news and the adjustment of this impact is limited by the cognition.

The Impact of Fake News on Affect

Fake news is strongly linked to affect. Martel et al. (2020) found that the influence of affect was not related to the perception of the accuracy of real news, but only to fake news. To further explain, Corbu et al. (2021) concluded through a survey experiment that fake news, whether positive or negative, increases negative emotions, meaning that people are more fearful and angrier, or decreases people’s satisfaction and enthusiasm. Taking COVID-19 as an example, Rocha et al. (2021), after analysing health-related fake news, noted that panic, depression, fear, fatigue and risk of infection caused by the information epidemic can lead to psychological distress and emotional overload and found that the dissemination of misinformation about COVID-19 was directly related to anxiety in different age groups. Similarly, by examining the relationship between emotions and COVID-19 fake news, Greene et al. (2021) found that the specific emotions expressed in the fake news can mislead readers’ affections. This shows that fake news influences the audience’s affects to some extent, especially the negative affects.

The Impact of Fake News on Behaviour

Human behaviour is shaped by the interaction between cognition, behaviour and environment (Fadillah, 2012). And affect often controls the tendency of human behaviour and decisions (Yeo & McKasy, 2021). The impact of fake news on audience’s cognition and affect unavoidably leads to changes in audience’s behaviour. Bastick (2020) found through a randomised controlled experiment that the stimulation of subconscious attitudes and emotions brought about by fake news prompts or alters people’s unconscious behaviours.

To further explain, Ladeira et al. (2022) found that because of the longer cognitive processing required for fake news, there are more opportunities for consumers to share information related to the brand, and consumers are more willing to share novel information related to it, such as fake news. In addition to this, Cantarella et al. (2023), in their study of the 2018 Italian general election, found that exposure to fake news favours the vote share of populist parties. Similarly, Allcott and Gentzkow (2017) noted that a piece of fake news is even more effective than a typical campaign advertisement in an election.

Furthermore, Corbu et al. (2021) found that fake news stimulates negative emotions which motivate audiences to further share fake news. In similar, Chuai and Zhao (2022) found through a questionnaire that the increase in anger stimulates strong anxiety and information sharing willingness as a motivation for the audience to further share fake news. In addition to this, Bakir and McStay (2017) argued that the emotions stirred up by fake news can cause losers in elections to become emotional and make inappropriate democratic decisions based on sentiment and disinformation. This shows that fake news can influence the behaviour of the audience, which consequently leads to economic and political changes.

The above literature analyses the impact of fake news on audience perception. It provides some references for this study, which also needs to research the impact of fake news on Douyin users’ perception. However, the above analyses show that there is still a lack of research on fake news on a particular social media, and the discussion of users, the main subjects directly affected by fake news on social media, is lacking. Moreover, most of the literature focuses on the relationship between cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects of the spread of fake news, while there is less discussion on the impact of fake news on audience perceptions. This study will fill this gap by analysing the impact of fake news on Douyin platform and its users.

Social Media and Journalism in China

Nowadays, social media has become a significant contributor to the fake news crisis (Heekeren, 2019). The development of digital technology has also allowed journalism in China to experience a significant change.

The ‘two Ws and one app’ refers to WeChat, Weibo, and News User Terminal. It is used to assess the development of all traditional and new media on mobile-enabled platforms in China (CAC, 2015). The implementation of this policy has led to a nationwide surge in online news production as traditional news media such as newspapers, radio, and TV stations accelerate their attempts to integrate with new media (Wang, 2021). At the same time, the development of technology and the Internet has pushed Chinese journalism into the new environment of Internet participatory journalism (Wang, 2023). Wang (2023) points out that Chinese media are unique compared to Western media. Therefore, the relationship between Chinese media and audiences under Internet participatory journalism differs significantly from Chinese characteristics. That is, the audience agendas precede the media agendas. In other words, the audience is more important than the media in deciding issues and attributes.

Similarly, Wright and Nolan (2021) found that user interactions such as clicks, likes, retweets, and comments have become the KPI of new media platforms and are regarded as an essential indicator for assessing the ability of news dissemination. In addition, the development of technology has also changed journalism’s industry standards and journalists’ writing habits in China. Wang (2021) points out that pictures, graphics, video and audio that attract attention have become four crucial elements of news writing and are widely used in online journalism.

The emergence of new media has brought diversified development to journalism in China, but it has also raised a series of noteworthy issues. While Internet participatory journalism makes it easier for users to access information and interact, Wang (2023) analyses user engagement on Sina Weibo, one of China’s vital social platforms, and finds that the content of its popular searches is mainly user-generated, with unverified commenting and retweeting, thus failing to ensure credibility and authenticity, leading to the spread of false information, fake news and rumours. Wang (2023) classifies the phenomenon of fake news on Sina Weibo into two types: out-of-context and clickbait. Out-of-context refers to the fact that public participation in news on Weibo is often detached from the context of the news event, with only specific opinions intercepted, lightly commented on and disseminated; clickbait, also known as ‘Title Party’ in China, refers to the use of exaggerated and sensationalised headlines by news publishers to attract netizens to click and browse. These two phenomena unavoidably lead to the spread of fake news in user engagement.

On the other hand, the innovation of news content in new media can attract users. However, compared with traditional media, Yuan (2023) argues that news in new media is more inclined to use symbols with emotional markers, more lines in headlines, and articles are broken down into smaller pieces and inserted into visual elements, leading to fragmentation of the overall content. This has also led some journalists to focus excessively on programming skills and interactive design while ignoring the content required for a good storytelling narrative (Wright & Nolan, 2021).

The boom in short video platforms in recent years has made the issues in journalism more obvious. Short video platforms based on content interactions use imperceptible algorithmic mechanisms to alter user interactions and push users into polarised echo chambers (Gao et al., 2023). By comparing the performance of the echo chamber effect across platforms, Gao et al. (2023) found that Douyin and Bilibili have a strong echo chamber effect of selective exposure and homogenisation compared to TikTok. As Zhao and Zhang (2024) stated, although the Internet cannot monopolise information, it can manipulate it, and citizens are easily persuaded. Thus, short videos are often used for modern visual activities.

In addition, Meng and Leung (2021) point out that earning money is a unique way for Douyin to attract user-created content compared to social media such as Facebook, Instagram and others. This is a point that in the era of user-generated content news, it is easy for people to spread exaggerated but false content due to the pursuit of financial gain. On the other hand, post-truth has become increasingly influential in social media. Wang (2022) notes that people often understand truth and falsehood with the dichotomous weapon of online thinking, that is, to create confusion and disbelief, as an emotional trigger to elicit anger and engagement, and as a driver of negative cohesion.

Literature Gap

Previous research has encountered some limitations in exploring why people tend to believe in fake news on social media and what effects fake news have on users’ perception. In the reviewed literature, these limitations include perspectival limitations, methodological constraints, as well as the lack of theories.

The perspectival limitations can be reflected in previous research. First, regarding fake news on social media, previous literature has focused mainly on internationalised social media such as Twitter and Facebook (Rhodes, 2021; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019). However, little literature has focused on Chinese social media, such as Douyin, Weibo, and other widely influential social media. This limited focus ignores China’s particular online environment and media landscape, limiting the understanding of fake news on Chinese social media. Furthermore, previous literature on post-truth has tended to focus on the political area (Bufacchi, 2021; Ruak, 2023), and the impact of fake news on social media has been more focused on broader aspects such as politics (Talwar et al., 2020; Yerlikaya & Aslan, 2020) and economics (Domenico et al., 2021). There is still insufficient exploration of post-truth representation in journalism and communication and the relationship between fake news and social media users.

The existing studies have methodological limitations. Past studies have tended to conduct quantitative research through large news samples to analyse the characteristics or impact of fake news (Tandoc Jr. et al., 2021; Ha et al., 2019). Little has been done through qualitative content analysis to provide a deeper understanding and interpretation of the relationship between fake news and users on social media. Moreover, few studies use media dependency theory to explain fake news on social media. Future research should focus on the characteristics of fake news in Chinese social media and its impact on users’ perception. This will help to more comprehensively and accurately explore the connotation of the post-truth era and the relationship between fake news and users on social media, providing new perspectives and theoretical foundations for fake news studies.

This research will study fake news on Douyin platform. In the context of post-truth, it will analyse the reasons why users believe in fake news and the impact of fake news on users’ perception. Thus, it will make up for the lack of relevant literature in the Chinese scenario, enrich the understanding of China’s unique media environment, and provide new references for the practice of journalism and short video platforms in China.

Chapter 3

Methodology

Research Design

Douyin, the leading short video platform in China, has become mainstream for people to understand the development of public opinion and events (Gao, 2023). However, its contents vary in quality and have become a disaster area full of fake news. Based on this, this study aims to explore the reasons why social media users believe in fake news and the impact of fake news on users by using Douyin as an example so as to contribute to the further interpretation of the causes and harms of the proliferation of fake news in China’s social media. Because of the purpose and research questions of this study, qualitative content analysis will be employed as the research method.

Qualitative research is related to interpretation and understanding, focusing not only on objective behaviours but also on the subjective meanings behind the behaviours, such as individual motivations, specific social and temporal contexts and so on (Aspers & Corte, 2019). Currently, fake news on Chinese social media, especially Douyin, the emerging short video platform, remains an unexplored phenomenon. Although this phenomenon is common, its complexity, especially in terms of users, still requires a better interpretation. Moreover, this phenomenon cannot be understood without reference to the characteristics of current Chinese journalism, such as post-truth and media integration. This remarkable phenomenon can be truly understood only by linking fake news on Douyin to these contexts and providing a deep and holistic interpretation based on rich data. Therefore, qualitative methodology is applicable to this study.

Qualitative content analysis is one of the tools for performing textual data analysis (Forman & Damschroder, 2007). It represents a systematic and objective way of describing a phenomenon and aims at analysing data and interpreting the meaning of it (Schreier, 2012). In the era of new media, users’ reactions and responses to fake news are usually reflected through messages on social media. In order to explore users’ behaviours and responses to Douyin’s fake news, data such as relevant user posts, comments, and other data need to be analysed to interpret the hidden meanings. Therefore, the use of qualitative content analysis can contribute to the research objectives of this study.

Unit of Analysis

This present study would analyse the fake news related posts made by users on Douyin within a time frame, which are widely disseminated and influential, as well as the comments under the posts.

Platform Selected

This study chose Douyin as the central social media platform to collect data. Similar to its international version, TikTok, Douyin is a video-sharing platform launched in 2016 by the Chinese company ByteDance. It is for users to watch and share short videos of 15-60 seconds made using filters, lip-sync templates and background music (Sadler, 2022).

Compared to social media such as Facebook and Twitter, Douyin’s user engagement is more focused on entertainment purposes (Choi et al., 2023). Automatically deriving user feeds based on user preferences and past user interactions with the platform is a unique selling point for Douyin (Ma & Hu, 2021). This algorithm is created to foster user engagement and provide benefits for scientific communication (Liang & Yoon, 2022; Habibi & Salim, 2021). Moreover, another driver of Douyin’s emergence is its interdisciplinary audience (Rejeb et al., 2024).

As of January 2023, Douyin has reached 700 million users in the Chinese market (Li & Wang, 2023). In the third quarter of 2023, Douyin ranked second among China’s major social media platforms in terms of monthly usage at 78.4% (Thomala, 2024). Its monthly active user growth and per capita single-day usage hours ranked first among typical new media platforms in China.

In 2023, Douyin introduced a new rule to display the real names of creators with more than 500,000 fans on the front. However, ordinary users only need to authenticate their real names when registering their accounts, and this information will not be shown to the general public. As a result, users are still presented with nicknames when making comments, reposts and other interactions.

Douyin has exploded in popularity, and many celebrities, companies, and organisations have moved into the platform. In addition to identities such as enterprises, musicians and special effects artists, Douyin has also set up Multi-Channel Network (MCN) organisations and social institutions certification. According to Douyin’s conditions, social institutions include media organisations such as newspapers and magazines, state institutions such as party and government organs, and other organisations such as schools. In 2018, the SASAC News Centre, which belongs to the State Council of China, formally joined Douyin and opened the account “Guozixiaoxin”. Since then, various organisations such as museums, SWAT teams, and the Communist Youth League have been active in Douyin, positively seeking change through this new form of communication.

Traditional news media eager to integrate with new media is present. At present, with ‘news’ as the keyword to search, the number of fans is only over 1 million, and the officially certified account is more than a hundred. In addition to this, there are also a large number of ‘Yingxiaohao’ accounts that are mainly working with carrying all kinds of information. Douyin has become a news-gathering place that must be addressed.

Time Frame

The time frame of this study is from March 15 to 22, 2024. March 15 is World Consumer Rights Day; on this day, China Media Group, the Government of the People’s Republic of China, and the China Consumers Association co-organised the 3.15 Gala to expose incidents that infringe on consumer rights in society.

On March 15, 2024, the article ‘Woodpecker Consumer Surveys: What is the starchy sausage that is hitting the streets made of?’ was posted on China National Radio (CNR), China’s state-level radio station website. With the aim of protecting consumers’ rights, the news report describes the problems found by the journalist in the process of investigating the ingredients of starch sausage: starch sausage is made of bone paste, which is not recommended to be eaten by human beings. At the same time, the Douyin account of CNR also released this news in the form of a short video.

On that day, with the intensity of the 3.15 Gala, Yingxiaohao made this news into short videos posted on Douyin. Then, more and more Yingxiaohao reprocessed and spread it, with increased user participation. ‘Starchy sausage gets a bad rap’ became trending on Douyin and spread rapidly. However, when retelling the news article, Yingxiaohao added the message ‘3.15 Gala exposed starchy sausage’ and claimed with great personal emotion that ‘bone paste is made from slop and the trimmings of slaughterhouses,’ expressing disappointment and anger towards starchy sausage.

However, the ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ that caused the whole network to discuss is actually a typical fake news. Firstly, the 3.15 Gala did not mention any starchy sausage related problems, and the earliest short video about ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ was released even before the 3.15 Gala was started. Secondly, the reporter pointed out in the article that ‘some starchy sausage merchants use bone paste,’ which does not mean that all starchy sausage merchants use bone paste as raw material. As of March 16, three out of the four starchy sausage brands mentioned in the hot trend had already issued statements that they did not use bone paste in their products.

Thirdly, in the process of investigation, the reporter learnt from the internet search that bone paste is mostly used in pet food. Therefore, the reporter chose to ask the pet food merchants, and the pet food merchants said that ‘bone paste is not recommended for human consumption.’ The logic of this process is not sound, just as corn is also made into feed for livestock, if asked feed manufacturers whether corn feed can be consumed by humans, then the answer is also not recommended for human consumption. In addition, bone paste food has actually been around for more than a decade, and it is widely used both at home and abroad in the production of foods such as sausages and meatballs, and it is actually a very common ingredient. Therefore, as long as the bone paste complies with the food production standard, it can be consumed by human beings.

The ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ fake news began on March 15, 2024 and was clarified in the following days after a massive discussion. This series of processes all took place within a week. Therefore, this study chose this period as the time frame because it can provide more material for data collection.

Sample Size and Sampling Method

In order to determine the sample size, this study followed the principle of data saturation. Data saturation is widely recognised as a driver in identifying the adequacy of sample size and determining the achievement of the expected research objectives (Fusch et al., 2018). Reaching data saturation is a condition where there is no new data, no new themes, no new codes, and no ability to replicate the study (Aguboshim, 2021). It is an important aspect to consider in qualitative research, requiring that data be collected from information providers to the point that it is impossible to collect more information (Mwita, 2022).

All samples in the present study would be selected from Douyin through the purposive sampling method. This strategic sampling method looks for cases that are most likely to provide useful information by identifying and selecting the most effective use of limited research resources to address the research objectives and questions (Campbell et al., 2020). As non-probability sampling, the investigator must decide who can be included in the sample based on certain characteristics (Thomas, 2022). A valid purposive sampling must have clear inclusion criteria and rationale (Mweshi & Sakyi, 2020).

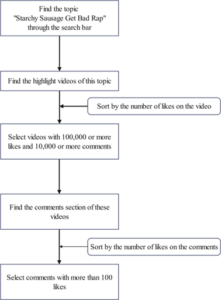

A series of multi-layered selection criteria would be used to select the available data for this study. Firstly, the Douyin account used had to be brand new to avoid algorithmic bias. Secondly, the selected videos and comments related to the ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ fake news must all come from Douyin, and the selected period of time is from March 15, 2024 to March 22, 2024. Additionally, the selected ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ fake news videos must have at least 100,000 likes with 10,000 or more comments. The selected comments must be from a video that meets the above criteria, and the comments must have at least 100 likes. If there are still replies under a comment that meets the above criteria, and the replied comment can react to users’ perception, then the replied comment is also

included. Moreover, only select text comments, including text in pictures. Finally, when filtering, videos with the tag ‘Starchy sausages get a bad rap’ but with content unrelated to the fake news discussion, such as tutorial videos on homemade starchy sausage, should be filtered out; as well as meaningless comments, such as those with no content other than @friend.

Figure 1: Flowchart of Sampling Procedure on Douyin

Ethical Considerations

In this study, ethical considerations are significant, especially during the collection and processing of data. Ethics can address the related ethical issues during research practice and as a way to ensure that scholars are following sound research principles in practice (Mirza et al., 2023). Therefore, adding certain ethical considerations to ensure the credibility and authenticity of the data is crucial in this study.

Before data collection, it is crucial to understand the terms and conditions of Douyin platform. As the source of all the data in this study, it is vital to guarantee that the use of Douyin platform’s content as research material is allowable. Douyin’s terms and conditions stipulate the legality of downloading user-posted content without infringing users’ legitimate interests. It also defines the copyright of the content posted by the users and the privacy of the users. Using Douyin’s terms and conditions as a reference, unethical behaviour can be avoided in the research process.

During the data collection process, it is necessary to focus on the research’s trustworthiness. Firstly, the data collected must have an accurate attribution: the specific user who posted the content. Secondly, it is important to avoid any alteration of the collected data, whether the source or the content, to ensure that it is original and to avoid manipulating the data by modifying the source or taking it out of context. In terms of data retention, confidentiality has to be guaranteed. Preventing data manipulation by restricting access to the data is valuable.

During the translation process, it is essential to keep neutrality. The researcher needs to reduce personal intrusiveness and bias to ensure the research’s credibility. In qualitative research, translation is often a significant source of bias (Mirza et al., 2023). Since the data collected in this study is in Chinese, the translation process is essential. In the process of transcription and translation, utmost effort would be made to avoid introducing personal bias and maximise the credibility of the data.

Data Analysis

The present study employed thematic analysis in an inductive way to interpret Douyin users’ perceptions of fake news and the impact of fake news on Douyin users. Thematic analysis is an accessible and theoretically flexible approach to analyse data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It is a qualitative method of finding repeated meanings across data and is significant in interpreting phenomena (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). By identifying, analysing and reporting on themes, it both responds to the reality and uncovers the surface of that reality (Braun & Clarke, 2019). Qualitative methodologists typically regard thematic analysis as a flexible, subjective, creative process (Liu, 2023). The accessibility, transparency and flexibility of thematic analyses make the analysis more valid. Meanwhile, data-driven inductive methods allow for a more open exploration of the information and a more comprehensive understanding of the data.

The process of data analysis will be done by transcribing and organising the collected posts and comments. The collected data would be translated from Chinese to English and organised according to the attitudes of the posts and comments towards the fake news event. Then, the researcher needs to thoroughly reflect on the understanding of the data, conducting at least two readings to ensure familiarity with the data.

Next, the coding process would be meticulously done. It is important to ensure that the codes capture the qualitative richness of the phenomenon and describe the large amount of data (Boyatzis, 1998; Joffe, 2012). Inductive coding would be applied to the collected data. Through detailed reading, the large amount of initial data will be assembled into smaller units (Saldana, 2013). The researcher would assign a word or phrase to the corresponding unit of data to code and classify the codes.

Good codes can be developed into themes that answer research questions (Charmaz, 2001). After categorising and combining the relevant codes, the code would be organised into potential themes that reflect users’ attitudes towards fake news as well as the impact of fake news on users. Use clear names to define and name themes. At this stage, relationships among themes, codes, and between themes and codes can be explored to further the understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Finally, a critical reflection on the themes is necessary. Firstly, it is crucial to ensure that the themes respond to the essence of the codes that are relevant to the research question, answering users’ perception towards fake news and the impact that fake news has. Next, the validity of the themes is ensured. The rationality of the research process is guaranteed by revalidating the coding process and selecting themes.

Chapter 4

Results

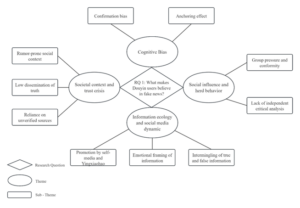

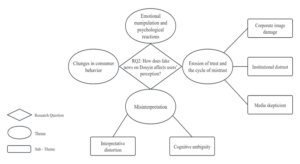

This chapter will present the insights of Douyin users’ reaction to fake news through content analysis of user comments on Douyin’s ‘Starch sausages get a bad rap’ fake news. Eight themes were identified and extracted through the process of thematic analysis. They were: (1) Cognitive bias; (2) Social influence and herd behaviour; (3) Information ecology and social media dynamic; (4) Societal context and trust crisis; (5) Emotional manipulation and psychological reaction; (6) Erosion of trust and the cycle of mistrust; (7) Misinterpretation; (8) Changes in consumer behaviour.

Figure 2: Themes for Research Question 1

Cognitive Bias