Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Development and Evaluation of a Mutual Support Program for Parents of Children with Developmental Disorders in Japan

Yutaro HIRATA1*, Yutaka HARAMAKI2, Yasuyo TAKANO3, Kazuhiko NISHIYORI4, Rie OTSUKA4, Sae NAKAMURA4

1Kagoshima University, 1-21-30 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japa

2Hiroshima University,1-3-2 Kagamiyama, Higasi Hiroshima, Hiroshima 739-0046, Japan

3Aichi Shukutoku University, 2-9 Katahira, Nagakute, Aichi, 480-1146, Japan

4Saga prefecture tobu Developmental disabilities center yui, 3300-1 Azanishitani Ejima-machi Tosu-shi Saga, Japan

Received Date: August 05, 2022; Accepted Date: August 15, 2022; Published Date: August 25, 2022

*Corresponding author: Yutaro HIRATA, Kagoshima University, 1-21-30 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan. Email: hirata@leh.kagoshima-u.ac.jp

Citation: HIRATA Y, HARAMAKI Y, TAKANO Y, NISHIYORI K, OTSUKA R, NAKAMURA S (2022) Development and Evaluation of a Mutual Support Program for Parents of Children with Developmental Disorders in Japan. Adv Pub Health Com Trop Med: APCTM-156.

DOI: 10.37722/APHCTM.2022302

Abstract

This study aimed to develop an interaction program for mutual support exchange for the parents of children with developmental disorders, identify the most urgent issues in the program, and the potential difficulties of implementation by the qualitative method. In Study 1, practical activities were reviewed from the perspective of process evaluation for staff meetings and participant questionnaires. Program structure and intention were presented, and the innovations in program structure were described. Practical activities were discussed from the following perspectives: (1) type and content of activities; (2) duration and frequency of program implementation; (3) number and characteristics of users, characteristics of program implementers, and information on program provision methods: (i) implementation arrangements, (ii) degree of service, (iii) problems and negative effects of implementation, (iv) matching between planning and implementation, (v) stability, and (vi) utilization. In Study 2, we conducted a categorical analysis of participant questionnaires (n=157), specifically descriptive data on parents’ program experiences. The effects of the program were described in three major categories: “Experiences through opportunities for reflection,” “Experiences through interaction with other parents,” and “Increased motivation.” Moreover, the contents of the program and the characteristics of the structure that produced the effects were studied. The relationship between the categories also showed the mechanism of the program’s effectiveness, in which opportunities for reflection and mutual interaction among parents lead to increased motivation. In the future, it is important to examine the detailed mechanisms of the program and it is expected that further effective activities will be developed and evaluated with studies in more countries and regions.

Keywords: Children with developmental disorders; Family support, Mutual interaction support

Introduction

Support for families with children with developmental disorders[1]has recently garnered research attention. Parents of children with developmental disorders are likely to experience various difficulties such as anxiety and a sense of burden in child rearing. For example, in addition to difficulties in understanding and dealing with the characteristics of the disability [1] as well as anxiety about the child’s future [2], it is challenging to obtain empathetic understanding from their community [3, 4]. Nakata [3] points out that the stress in parenting children with developmental disorders is higher compared with parenting typically developing children. In fact, in the Law for Supporting Persons with Developmental Disabilities revised in 2017 [5], support for families and others of persons with developmental disorders was added, and the importance of such support is further being characterized legally.

Support for parents of children with developmental disorders can be divided into two main categories: formal and informal. Formal support is provided by medical and rehabilitation institutions and various consultation organizations; informal support is provided by other parents of children with developmental disorders. Examples of formal support include parent training [6] and parent programs [7] as approaches to enhance parenting skills and deepen understanding of such children, as well as individual counseling and consultation at specialized institutions. However, informal support also plays a significant role, especially in terms of providing opportunities for interaction among parents of children with developmental disorders [8]. Examples include mutual support activities for parent meetings as peer support [9] and parent-mentor activities [10, 11, 12]. In fact, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has continuously promoted parent-mentor activities since 2010 [13]; furthermore, the Act on Support for Persons with Developmental Disabilities stated that “the MHLW shall appropriately provide consultation, information and advice, support for activities for families of persons with developmental disorders to support each other and other related persons.” The Act has been amended to state that “efforts shall be made to appropriately provide consultation, information and advice, support for activities for families of persons with developmental disorders to support each other, and other support.” These points suggest that the development of not only direct support for guardians, but also necessary support for the families of persons with developmental disorders is an urgent issue in the support of children with developmental disorders in the local community.

The importance of support and connections among parents has been recognized in numerous domestic and international practices and initiatives, such as the Parent Mentor Program [14, 15], Parents’ Association [16], and the Parent-to-Parent program [17, 18]; however, these are not limited to people with developmental disorders. In addition, the significance of these activities and efforts to promote them have also been shown both in Japan and abroad. Participation in these activities helped parents experience reduction in loneliness in parenting [19], obtain a sense of security [19], gain self-esteem and confidence [20], and become empowered [20].There are further psychological aspects such as a sense of security [19], self-affirmation and confidence [20], empowerment [21], acquisition of concrete information [16], and improved skills [21]. According to Nakamura and Ikeda [22], mothers of children with developmental disorders perceived family and friends as “people who helped me in raising my child” more than professional organizations. These studies suggest that interactions among parents with similar experiences may have diverse usefulness for parents.

However, challenges in parent-to-parent interactions also exist; these are discussed from three perspectives: parents as participants, support providers, and lack of research on these. First, from the parents’ perspective, issues include the lack of opportunities for mutual exchange among parents in the community, the psychological hurdles to participation due to the uncertainty of the nature of the activities, and the lack of time for parents who may both work away from home. Thus, for parents to gain opportunities for mutual exchange, it is assumed that they must be active; it is difficult for them to search for information locally and conduct exchanges with other parents on their own in the midst of child-rearing as they lack the necessary psychological and time resources.

Next, Haraguchi [23] identified regional differences in the implementation of training programs, an insufficient number of parent-mentors, and the existence of mentors who receive parent-mentor training but do not register or engage in activities. In response to these challenges for parent-mentor training led by public organizations such as local governments and support centers, the Parent Mentor Guidebook Development Committee [12] highlighted the importance of establishing a Parent Mentor Coordinator to coordinate the matching and opportunities themselves. This requires further discussion, including the accumulation of practical knowledge of coordinators.

Another issue that remains to be addressed is how to adapt parent-mentor and parent-to-parent activities conducted in other countries to the Japanese culture and child-rearing systems. Haraguchi [23] point out that it is often difficult to apply support activities developed abroad through one-on-one matching directly to the Japanese population; it is more helpful in the current situation to seek culturally consonant forms that match the Japanese cultural background, especially in terms of interpersonal relationships and regional characteristics.

Furthermore, there are several challenges in research: the definition of family interactions and the criteria for comparing and verifying research are unclear [24], the identification of effective outcomes is difficult, and theorizing about parent-teacher conferences is insufficient. In particular, although there is an accumulation of empirical knowledge on parent-teacher associations, each association is highly idiosyncratic, and hence, there are multiple methods of approaching parents. This situation may be due to the fact that the associations are particular to the people concerned.

From the reports of clinical practice, surveys, and research, it can be seen that there are needs that are not being met by existing approaches; psychosocial support for parents of children with developmental disorders at the present stage is largely absent. It would be useful to consider more diverse family support for these parents in the community who have been difficult to target in the past, and to consider how to support mutual interaction among parents from an unconventional perspective.

The MHLW [13] has proposed the creation and expansion of a new system of family support systems, including family skill improvement support programs, peer support promotion programs, and other family support programs for the individual and family, in addition to parent-mentor and parent training programs. The parent-mentor program, which is currently the most systematically implemented and promoted in Japan, has only recently been put into practice, and effective activities and support systems need to be described [23]. The meaning and extent of mutual interaction for parents need to be further examined both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Based on the situation described above, this study aims, first, to report on the details of the development and implementation of a mutual exchange support program for parents of children with developmental disorders in a certain community, and to clarify its significance, important points, and emerging issues. Second, a qualitative survey is conducted to clarify the effects of the program and to discuss innovations, considerations, and issues to be addressed.

Based on this, we aim to contribute to the development of a mutual exchange support program for parents of children with developmental disorders.

Materials and Methods

First, the background of the program development and its implementation will be reported. Next, a qualitative study will be conducted, focusing particularly on the effectiveness of the program as perceived by the participants.

Ethical Considerations

Approval for this research was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Law and Letters of Kagoshima University.

Study 1

The Program

History of Program Development and Positioning In the Support System

The authors have conducted a training program for parent-mentors, implemented by a social welfare corporation commissioned by a local government, since 2012. As a result, we have developed parent-mentor activities not in the conventional one-on-one, face-to-face format, but in an informal tea party format, and have inspected and created a training program accordingly. The issues raised include how to recruit new parent-mentors and the need to promote mutual support through acquaintanceship and connections not only among parent-mentors, but also among parents in the community. Therefore, the main objectives of the training program were (1) to spread awareness of the importance of developmental disorders and family support in the community, and (2) to raise awareness of the existence and activities of parent-mentors.

The target audience was assumed to be “parents of children with developmental disorders.” Based on the above background, the content of the program was reviewed with the aim of providing a basic understanding of the difficulties experienced by parents, the changes in and current knowledge of disability acceptance and understanding, promoting understanding of children and parents themselves, promotion of communication among parents, and ongoing intermittent relief for parenting difficulties through participation in this program. The prefecture in which this study was conducted is based on lifelong support during developmental stages, and various types of support are incorporated at each developmental stage, such as infancy, school-age, and adulthood.

Developing and Structuring the Program

The following points were taken into consideration when developing the program: (1) to consider parents’ knowledge, their psychological state, and the stages of understanding and accepting disorders; and (2) to provide an opportunity for parents to interact with each other through experiential learning, and to ensure their psychological safety.

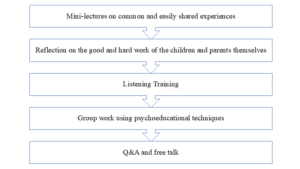

Figure 1: Program Content.

Program Description and Details

(Table 1) shows the type and content of activities in the program. 2. Explain the necessity of consciously looking for the above points, especially since it is difficult to pay attention to them in the process of child rearing. 3. Allow time for each parent to think and write on the worksheet. Also, to provide an opportunity to reflect on oneself and one’s children, who rarely think about it. (Ask parents to ask questions when necessary. If they have any questions, and consider the difficulty of writing, for example, that it is not necessary to write aggressively or that it is acceptable to picture it in one’s mind.) · Neutral listening · Intimidating listening · Positive listening

Details

Intention

Points to note

Content: Mini-lecture on experiences common to parents of children with developmental disorders

Introduction to various parental experiences, understanding of disability, multiple processes and models of disability acceptance, and the importance of peer support.

Orientation on the significance of interaction among parents, to sort out the difficulties and parental discomfort by sharing the stresses and difficulties that tend to occur as well as various experiences of child rearing as knowledge in advance.

Content: Reflection using worksheets for children and parents themselves

1. Explain the meaning of looking for, and thinking about, the good points and the things they are doing well.

Prepare in advance as materials for safe interactions among parents.

Use a PowerPoint presentation to show specific examples.

Content: Teaching and experiencing how to listen

The key to listening.

Model in advance so that communication between parents does not become one-sided or critical.

Content: Group work using psychoeducational techniques

The facilitator will set aside time to focus on the reflections on the worksheet and share them in turn with the group. Then, the entire situation is reviewed and shared as needed with the whole group.

To provide an opportunity for parents to hear from each other about themselves and their children, who are often viewed negatively, and to learn from the experiences of other parents as a modeling study.

Manage your time.

Contents: Q&A and free talk

A question-and-answer session held as a whole. After the session, inform the parents that the venue will be left as it is for a while, so that the parents can interact with each other.

To be prepared so that time after the program was intentionally set aside for parents to interact with other and talk with staff from local support centers for people with developmental disorders.

The following four steps were particularly important in the structure of this program. The first was to present the key points of listening before communication among the parents. All participants were informed in advance of the “listening” attitude and how to listen; which increased participants’ preparedness for group work so that parents who spoke during group work would not receive one-sided advice or denial of the experience of their own child-rearing practices.

The second step was to prepare for the group work by having the parents fill in the worksheet with the content of their speech in advance. Reflections on “good points” and other comments made by individual parents were used as topics for sharing and exchange with other parents. This was intended to reduce the psychological burden that may occur during the interaction, such as tension between participants who have never met each other and anxiety about communication.

The third step was structuring of group work and using a facilitator. The facilitator provided a certain degree of structure to the group interaction, which was intended to give the parents an opportunity to talk about themselves and their children in a safe environment, and to listen to other parents with similar experiences, leading to a sense of security.

The fourth step was to actively communicate the background and purpose of the program to the parents through publicity. By doing so, we intended to avoid any discrepancy between the program and the parents’ readiness and reason for attending it.

Before and after the implementation of the program, the appropriateness of the content and structure of the program were discussed by clinical psychologists practicing at support centers for children with developmental disorders and clinical psychology university faculty members specializing in support for children with developmental disorders and their families; based on these, the necessary revisions were made.

Program Considerations

Subject of the Study

Minutes of staff meetings held before, during, and after the planning and implementation of four programs over a two-year period were the topic of the study.

Method of Analysis

The information on program implementation included the following:

(1) type and content of activities; (2) duration and frequency of program implementation; (3) number and characteristics of users, characteristics of program implementers, and information on program provision methods: (i) implementation arrangements, (ii) degree of service, (iii) problems and negative effects of implementation, (iv) matching between planning and implementation, (v) stability, and (vi) utilization. This information was organized and reviewed in the minutes of each implementation session.

First, the following are common to all program implementations in terms of implementation arrangements and characteristics of program implementers.

Participants were recruited for the program through the welfare departments of local governments, parent associations, and the JLSC website 2-3 months prior to program implementation. In addition to the schedule, location, application procedures, and lecturer introductions, a brief description of the course content was included in the literature. The local government’s support center for persons with developmental disorders was responsible for receiving and confirming participants, securing the venue, and preparing for the day of the course.

The program organizers included three university faculty members specializing in clinical psychology, support for children with developmental disorders, family support, and family therapy, and three staff members from the Saga Prefecture Developmental Disorders Support Center made up a total of six people, four of whom were licensed clinical psychologists and one was a licensed psychologist. The staff members included a parent-mentor, a teacher. Among the staff, there was a teacher who has been continuously conducting parent-mentor training as an instructor. Two staff members also continued to participate in the same parent-mentor training program. The program consisted of a 30−40 minute lecture and group work that lasted approximately 1 hour and 10-20 minutes.

The following issues were identified in the matching of planning and implementation in the free descriptions given by participants and in the meetings among staff members: (1) discrepancies between the participants’ expectations of the training and the actual content; (2) discrepancies between the content and structure of the lectures and work due to the diversity of participants, since the training was targeted at an unspecified number of participants; (3) the venue itself; (4) the appropriate scale of group work; and (5) the significance of conducting training at the regional level.

Based on these insights, the program was implemented by making appropriate improvements in publicity regarding the content and structure of the work targeting a wide range of parents, the scale of the event, and the number of participants in the group work sessions.

Other information such as dates and times of implementation, number and characteristics of users, problems in implementation, and negative effects are shown in the table below. 10:00am−12:00pm Region A 10:00am−12:00pm Region A 2:00−4:00 pm Region B 10:00am−12:00pm Region C

1st

2nd

3rd

4th

Date & Time

July 16, 2016

December 14, 2017

February 22, 2018

March 8, 2018

Number and characteristics of users

83 participants gathered through a publicity campaign called “Parents Raising Children with Developmental Traits.”

40 participants gathered through a publicity campaign called “Parents Raising Children with Developmental Traits.”

22 participants gathered through a publicity campaign called “Parents Raising Children with Developmental Traits.”

12 participants gathered through a publicity campaign called “Parents Raising Children with Developmental Traits.”

Implementation problems and negative effects

The respondents mainly raised issues related to group work, such as the difficulty in finding one’s good points and the short time required for group work, as well as requests for specific information.

There were opinions that the content of the lecture was not relevant to the people concerned and that it was difficult to understand the content and this remained as an issue for the future, especially regarding the mini-lecture.

Participants commented on the difficulty of finding their own good points and their desire to learn about support methods through case studies, suggesting issues such as mismatches with service provision and how to make them work on their task.

The burden of interaction between parents and guardians due to the content and the challenges of facilitator intervention were mentioned. In addition, it was pointed out that the staff should follow-up with the parents after the group work is completed. In addition, the group organization should be devised in accordance with the theme.

Study 2

In Study 2, a qualitative study was conducted from a post positivist epistemological perspective in order to clarify the participants’ experience of the program as parents of children with developmental disorders.

Research Participants

In total, 157 people of parents raising children with developmental traits (83 in City A in Year X; 40 in City A, 22 in City B, and 12 in City C in Year X+1) participated in the program and responded to a questionnaire.

Survey Contents

A simple survey was prepared for the purpose of understanding the usefulness and needs of the program. Participants were asked, “Was this training program helpful?” and responses were given on a 3-point scale: “very helpful,” “a little helpful,” and “not helpful.” In addition, participants were asked to provide comments and opinions about the course, as well as free descriptions of what they would like to see planned in the future (Table 3).

Analysis Method

We conducted a category analysis of the free descriptions in the post-implementation questionnaire. Specifically, descriptive coding [25] was performed from the perspective of “effects on parents created through the course.” The codes obtained were then grouped with similar ones to create categories, and those that could be further summarized were grouped into larger categories.

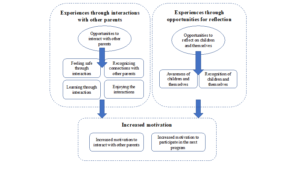

Next, the categories were arranged using the KJ method type A [26] and the logic theory of Yasuda [27] as aids to see determine the structure and flow of the program were related to the obtained categories on a time axis (Figure2).

Results and Discussion n=83 (%) n=40 (%) n=22 (%) n=12 (%)

1st

2nd

3rd

4th

It was helpful

48(58)

32(80)

17(77)

11(92)

It was a little helpful

28(28)

6(15)

4(18)

1(8)

Was not very helpful

7(8)

0(0)

0(0)

0(0)

No response

0(0)

2(5)

1(5)

0(0)

The analysis resulted in 93 codes, 11 categories, and 3 large categories (Table 4). In the text, major categories are indicated by { }, categories by <>, and data by “”

{Experiences through interactions with other parents}

This major category consisted of <Opportunities to interact with other parents>, <Learning through interaction>, <Recognizing connections with other parents>, <Feeling safe through interaction>, and <Enjoying the interactions>. This major category contained the highest number of codes, and was considered to be one of the central effects of this program through interaction.

{Experiences through opportunities for reflection}

This major category consists of <Opportunities to reflect on children and themselves>, <Awareness of children and themselves>, and <Recognition of children and themselves>. The parents found that the reflections provided them with opportunities to think about their children and themselves.

{Increased motivation}

This major category consisted of <Increased motivation to interact with other parents> and <Increased motivation to participate in the next program>, among others. The effect of increasing motivation for further interactions with other parents was confirmed.

Table 4: Category, major category, code frequencies and example of data.

Figure 2: Relationships among categories and major categories.

Figure 2: Relationships among categories and major categories.

Discussion

The program developed by the authors attempted to support mutual interaction and networking among parents of children with developmental disorders in the community. This paper described the program in detail and reported a qualitative study conducted to observe the effects of the program. The following is a discussion of the significance of implementing the program in the community, issues and points to keep in mind, the effects obtained from the program and their context, and implementation innovations and considerations to generate effects and issues, which were the objectives of this study.

Significance of Mutual Exchange Support Programs in Local Communities

As a prerequisite for verifying the effectiveness of the program content, comments such as “I have a chance to interact with other parents,” “I wish there were such a lecture from time to time,” and “This is the first time I have attended such a lecture” indicated that it is difficult for parents to obtain such opportunities in their daily lives. There was a lack of opportunities for interaction itself, as reflected in the categories. Considering the necessity of supporting mutual exchanges among families [13] and the small number of mentors [23] as future issues, the fact that we created opportunities in the community and obtained about 157 participants in two years is of significance for this practice. In addition, 108 (70%) of the 157 participants found the program “very helpful” and 39 (22%) found it “somewhat helpful,” indicating that the program was generally useful for the participants.

Support for persons with developmental disorders in Saga Prefecture includes not only family support but also various types of support at each developmental stage. Therefore, the existence of a place where parents can connect with each other in an informal manner may function interchangeably with formal support and lead to more seamless support.

However, in the future, it is necessary to consider the possibility that the program’s effectiveness is reflected more in the lack of opportunities themselves, in other words, in the scarcity of services provided, and to examine how the participants are connected to the parent-mentor training program.

Meaning Of and Points to Keep In Mind in Reflecting On Children and Oneself

Next, we will discuss the specific effects of the program on the participants. The categories obtained from the data were “Experiences through opportunities for reflection,” “Experiences through interactions with other parents,” and “Increased motivation”.

The categories of “Experiences through opportunities for reflection” were “Opportunities to reflect on children and themselves,” “Awareness of children and themselves,” and “Recognition of children and themselves”. This suggests that the program provided an opportunity for participants with diverse backgrounds, including parents with a variety of worries and anxieties, children’s characteristics, understanding of parents’ characteristics, and family relationships, to reflect on what they had experienced and to find positive meaning in their own experiences. The reason for this is that the participants were informed in advance about the significance of reflecting, that is, why and what they were looking back at; moreover, by focusing on the children’s and parents’ own “efforts” and “good points,” it was easier to engage in the task of looking back and have opportunities to gain new insights about the children and reevaluate their experiences. This was believed to lead to new insights about the child, opportunities to reevaluate, and motivation for the task of reflection. In addition, setting themes such as “good points” and “trying hard” may have functioned to intentionally avoid the tendency for parents to focus on their children’s problematic behavior and lack of confidence in their own parenting. It is also possible that the parents’ motivation was enhanced through the process of reflecting on their children’s behavior. The parents’ own reflection was supported by the parent program [7] and parent training [3], which are now widely implemented as family support programs, suggesting that these may be useful even in a single program. Further studies on the increase in motivation through follow-up interventions will be necessary in the future.

However, as mentioned in Analysis 1, a certain number of parents found it difficult to reflect upon their program experience. In particular, it was notably difficult for parents to reflect on their own good points and efforts. Therefore, it is necessary to assume the participation of parents with different understandings of disorders and psychosocial conditions when implementing the program. For example, it is necessary to clearly instruct all participants that not being able to think of something is not necessarily a bad thing that they do not have to write about things they do not want to write about, and to ensure that they are not forced to reflect on their own experiences. It is important not to make it a negative experience for parents who have difficulty in reflecting on their participation. However, this program was attended by a diverse range of parents, who had children of different ages and with different types and degrees of disorders. This may have had the effect of allowing participants to accept the experiences of others even if they had difficulty in reflecting on their own experiences, and to accept the experiences of others through their own experiences, an effect that can be obtained through mutual exchange among the participants. In the future, it will be possible to further clarify the mechanism of the practice by conducting interviews and other surveys from this perspective.

Fostering a Sense of Security and Safety in the Program

The “Experiences through Interaction with Other Parents” was largely composed of “Opportunities to interact with other parents,” “Learning through interaction,” “Recognizing connections with other parents,” “Feeling safe through interaction,” and “Enjoying the interactions,” suggesting that participants had a variety of experiences through their interactions with other parents.

The background to this is that through the presentation of listening points, worksheet descriptions, structuring of group work, and the presence of a facilitator, and the creation of an accepting atmosphere, the participants were able to increase their readiness to listen and speak, in other words, to interact with other parents from the public relations stage, and to safely talk about themselves and their children. This may have provided an opportunity for parents to talk to other parents who they felt had similar experiences, and to listen to other parents’ stories, leading to a sense of security through interaction, as well as to learning and recognition of connections with other parents. In addition, as mentioned earlier, the program was developed and set up based on the assumption of diversity among parents with various circumstances, conditions, and stages of development; this may have contributed to fostering of a sense of security.

Significance of the Comprehensive and Multilayered Program Structure

It is reasonable to consider that the abovementioned program contents, structure, and considerations are more significant in terms of their comprehensive and multilayered effects than in terms of their individual effects. Among the challenges in the program, one of the most notable points that we attempted to correct was that the facilitators and staff were able to observe the participants’ efforts intimately and intervene immediately, which was considered important for all activities. By creating such a comprehensive and multilayered structure, we were able to achieve the following results in the free descriptions: “I felt I was not alone” [19], “I felt less lonely” [19], and “I was able to talk with other parents who experience the same developmental disorder problems” [16, 19]. However, we do not know the mechanism underlying this phenomenon. Thus, it is necessary to clarify this mechanism by conducting more detailed and group focus interviews with the participants in the future.

Future Practice and Evaluation of the Program

There are three issues to be addressed in the implementation of and further research on this program. The first is the significance of the mini-lecture in the first half of the program. The data obtained indicated that there were few categories of effects related to the mini-lecture, and as indicated in Analysis 1, some of the participants also stated that “I could understand what was being said, but I could not follow it “and “I felt a little uneasy at the beginning. I wondered if this kind of workshop would continue until the end.” Some of the participants also expressed their opinions. However, during the development of the program and review, it was also noted that understanding the experiences common to all the parents and the effects and the meaning of mutual support before having the parents actually experience the interaction provided a sense of security that they were not alone. This may have motivated mutual exchange and increase their sense of safety, which may have facilitated interaction among the participants during the group work in the latter half of the session. Therefore, further study is needed on the content of the mini-lecture and the program structure.

The second point is the linkage between the participants’ needs and the subsequent support. The evaluation of the program did not clarify whether it was able to connect participants’ need for the program, the program’s response to those needs, and the support necessary to meet the needs after participation. Further development is needed in this area.

The third point is the evaluation of the program from the perspective of the government, which is the stakeholder of the program, and scrutiny of the information necessary for evaluation. For example, questions regarding the number of participants who subsequently attended the parent-mentor training, the actual state of interaction between the participants, the optimal number of staff needed for the program, the expertise and knowledge required, and how effective the program actually was, are all likely to arise. What kind of program is actually effective and how effective is it? While the “what” can be explained to a certain extent in this study, quantitative research, such as a questionnaire survey, will be necessary to determine the “how” in the future. It will also be necessary to respond to the needs of various stakeholders through follow-up surveys of the participants.

Data Availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (J190000147).

Acknowledgments: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the parents who participated and cooperated in this study.

Reference

- T Yamane (2010) “A Qualitative Research of Mothers in Recognition that their Child has a High-functioning Pervasive Developmental Disorder.” Journal of Family Education Research Institute 32: 61-73.

- Song H, Ito R, Watanabe H (2004) “A Study On Support Needs Of Parents And Children With High-Functioning Autistic Disorder And Asperger’s Disorder.”Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei University. Section I, Science of Education 55: 325-333.

- Nakata Y (2009) “Developmental Disabilities and Family Support: What is Disability for Families?” Gakken Plus.

- Yutaro H (2018) “What are the Guardians of Children with Developmental disorders’ Experiences with School Personnel?” Japanese Journal of Clinical Psychology 18: 229-240.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Developmental Disabilities Support Act. (https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/tokubetu/main/1376867.htm)(2020年06月19日)

- Nakata Y (2017) “Parent Training and Parental Support: Current Status and Future Issues (Special Feature: Expanding Parent Training in the Community) Asp heart = Asp heart : Pervasive Developmental Disorder for Tomorrow 16: 14-18.

- Aspire Elde’s Association (2015) Parent Program Manual for Fun Parenting (for Professionals and Supporters). Aspie Elde no Kai, a Nonprofit Corporation.

- Nakata Y, Tsutsui T (2014) “Maternal Stress from Caring for Children with Developmental Disorders.” Bulletin of Psychological Clinic, Rissho University 12: 1-12.

- Tsuzan K “Establishment and Developmental Process of Community Work by “Parents as A Party” of People with Developmental Disabilities” Bulletin of Seinan Jo Gakuin University 18: 63-73.

- Haraguchi H, Inoue M, Yamaguchi H, et al. (2015) “Peer-to-peer Support Programs for Parents of Children with Developmental Disabilities: Current Issues of Parent Mentor Programs in Japan.”Journal of Mental Health: Official Journal of the National Institute of Mental Health, NCNP, Japan 28: 49-56.

- Japan Parent Mentor Study Group Nonprofit Organization. 2020.

- Parent Mentor Guidebook Preparation Committee. Parent-Mentor Guidebook for Family Support by Families. 2018.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Policies to Support Persons with Developmental Disabilities. 2019. (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2005/04/tp0412-1.html

- Autism Society of Japan.Parent Mentor Training Course: Human Resource Development Project for Family Support of Autistic Children.(2006).

- Autism Society of Japan. Nippon Foundation Grant Program for Human Resource Development: Project for Family Support of Autistic Children Report. (2006).

- Inoue R (2008) “Literature Review of Parents Groups in Japan.”Journal of Japanese Society of Child Health Nursing 17: 59-65.

- Santelli B, Turnbull A, Marquis J (1995) “Parent to Parent Programs: A Unique Form of Mutual Support.”Infants and Young Children 8: 48-57.

- Santelli B, Turnbull A, Sergeant J, et al. (1996) “Parent to Parent Programs: Parent Preferences for Supports.”Infants and Young Children, 9: 53-62.

- Ainbinder JG, Blanchard LW, Sullivan LK, et al. (1998) “A Qualitative Study of Parent to Parent Support for Parents of Children With Special Needs. ”Journal of Pediatric Psychology 23: 99-109.

- Barker MS, Nancy P, Chris B (2001) “The Benefits of Mutual Support Groups for Parents of Children With Disabilities.”American Journal of Community Psychology 29: 113-132.

- Law M, King S, Stewart D, King G (2002) “The Perceived Effects of Parent-Led Support Groups for Parents of Children with Disabilities.”Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 21: 29-48.

- Nakamuraand Y (2009) “One Consideration About the Support to Mothers Who have Children with Developmental Disorders.”The Bulletin of Health Science University 5: 115-122.

- Haraguchi H (2015) “Current Issues of Parent Menter Training Program in Japan”. The Japanese Journal of Autistic Spectrum: Practice and Clinical Reports 12: 63-67.

- Nakaji N (2012) “A Review of Studies on Groups for Parents of Children Not Attending School in Japan: 1990-2010.”Japanese Journal of Counselling Science 45: 239-247.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J (2020) Qualitative Data Analysis (4th ed.). Sage. 2020

- Kawakita J (2017) Ideas Revised – For Creativity Development. Tyuoukouronnsinsyo. 2017.

- Yasuda T (2011) Program Evaluation To Improve the Quality of Interpersonal and Community Assistance. Shinyousya.