Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Changes In Partnership And Sexuality In Persons With Acquired Brain Injury (ABI)

Simona Tičar, Eva Ristič*

Center KORAK for individuals with acquired braininjury, Kidričeva cesta 53, 4000 Kranj, Slovenia

Received Date: August 18, 2022; Accepted Date: August 26, 2022; Published Date: September 09, 2022

*Corresponding author: Eva Ristič, Center KORAK for individuals with acquired braininjury, Kidričeva cesta 53, 4000 Kranj, Slovenia. Email: eva.ristic@center-korak.si

Citation: Tičar S, Ristič E (2022) Changes In Partnership And Sexuality In Persons With Acquired Brain Injury (ABI). Adv Pub Health Com Trop Med: APCTM-158.

DOI: 10.37722/APHCTM.2022404

Introduction

Partnership and sexuality after ABI are challenging. ABI affects physical, mental, emotional, behavioral, and social functioning [1]. Sexuality and partnership are parts of the holistic rehabilitation process.

ABI-related deficits can shake the core of a partnership by affecting roles, responsibilities, trust, communication, emotional connections, and behavior toward each other [2]. ABI has a direct effect on sexual function or an indirect effect on motor, sensory, cognitive, behavioral, and emotional functions [3]. Changes in individuals with ABI also appear to affect the sexuality of their uninjured partner [4]. Hormonal changes affect the production of sex hormones [5].

Partnership Changes after ABI

- The relationship changes if the partner’spersonality has changed after ABI (Ahman, Yates 2017),

- Partners often take on therole of guardian for an injured partner (Rodger, Yurdakul, 1997 in Ahman, Yates 2017).

- Partnership reinforcements, family dynamics (Ahman, Yates 2017), and interaction of couples changes [2].

- Lack of inhibition results in socially inappropriate behavior (inappropriate touch in different situations and interactions), impulsivity, aggressive behavior, and hyper sexuality (Blacker by, 1994) [6].

- Changes in intimacy (asexual acts) – as emotional, physical, and mental closeness between two people, which is often accompanied by romantic emotions. Intimacy is asexual acts such as holding hands, caressing, kissing, and physical intimacy. Intimacy is affected if the victim has a lack of insight into their behavior or problems with anger management [2].

- Decreased satisfaction in the relationship, social-emotional abilities, and functioning are challenged (Abigail etc., 2007).

The partners of people with ABI who have been in a long-term relationship (more than 15 years) accepted the changes of their partner and did not separate. The likelihood of marital separation or split between couples increases with time from injury. Between 5 to 6 years after the injury is the common period for the split to happen (Rodger and Yurdakul, 1997). A mature and responsible attitude of the injured partner contributes to the stability and survival of the relationship after PMP (Rodger, Yurdakul, 1997).

The partners of people with ABI who have been in a long-term relationship (more than 15 years) accepted the changes of the injured person and did not break up. The probability of separation between partners increases with time from injury, with the turning point for relationship breakdown being approximately 5 to 6 years after injury (Rodger and Yurdakul, 1997). The mature and responsible attitude of the injured partner contributes to the stability and survival of the relationship after ABI (Rodger and Yurdakul, 1997).

Changes in Sexuality after ABI

- The decreased desire for sex and less interest in sexual intercourse [7].

- Hypersexuality or hyposexuality [8], ejaculation disorders, anorgasmia, and decreased vaginal moisture [9].

- Loss of libido [9].

- Difficulty controlling sexual behavior, inappropriate comments, and sexual behavior.

- Problems with arousal.

- Difficulty in achieving or maintaining an erection [7, 10].

- Irregular menstrual cycles, difficulty conceiving, decreased amount of cervical mucosa, increased growth of hair on the face or body, worsening acne, changes in sex drive, and recurrent miscarriages [9].

- Lack of sexual desire in women, arousal, sexual pleasure, and orgasm (Strizzi et.al, 2015; Hibbard et. Al., 2000).

- Premature ejaculation [11] is the most common male sexual disorder.

- Reduced sexual/erotic thoughts or fantasies arousal, sexual behavior, and difficulty achieving orgasm in women (in Sander, 2012) [12].

- Disrupted sexual behavior – sexual content manipulation, genital exposure, and public masturbation. Sexual behavior may occur in appropriate contexts [13].

- Sexual dysfunction following ABI is associated with symptoms of depression (in Sander etc., 2012) [12] and anxiety.

Sexual Problems Are Affected By

- Body changes, gender identity, self-image, depression, and anxiety [14], Tyerman, Humphrey, 1984).

- Reduced self-confidence, deterioration of mood, the elevation of anxiety, and communication problems (dysphasia -difficulty to express thoughts in words), which can make it difficult for a person to express love and affection or develop a relationship [3].

- Medications (antidepressants) can cause erectile dysfunction [3]. Impaired cognitive functions, including impaired control of behavior, communication, social judgment, and egocentrism affect the ability to have quality interpersonal relationships [4].

- Physical impairment – spasticity, poor balance, poor control of fine movement, and tremors (ataxia).

- Poor control of swallowing and consequent salivation, reduced sensitivity or. Hypersensitivity affects sexual pleasure [3].

- Loss of taste and smell correlates to a decrease in sexual arousal and pleasure.

- Limited opportunities for intimate contacts [4].

- Decreased ability to become physically aroused andexperience orgasm [4].

- People aged 46–55 report the greatest reduction in the quality and frequency of their sexual experiences [4].

Method

Participants: The case study involved 16 people (25% women and 75% men) who suffered a traumatic or non-traumatic brain injury. Allare involved in the process of long-term and comprehensive rehabilitation at Center KORAK for individuals with acquired brain injury. Before publishing research, individuals signed written consent forms.

Measures: Diagnostic-oriented open type of interview The structure of the questionnaire was adjusted according to the cognitive and emotional characteristics of people with ABI. The frequency of interviews depended on the ability of people with ABI. GRISS questionnaire (Rust and Golombok, 1986a). Partnership Assessment Form (RRF) (David, 1996; in Bele, 2011) [15].

Procedure: The survey was conducted in January 2022. After obtaining the consent of the participants, we applied a questionnaire. The results were processed with the SPSS program. We researched the areas in more detail with a diagnostic-oriented interview [16-23].

Results YOUNG PEOPLE WITH ABI WHO WANT PARTNERSHIPS AND SEXUALITY (can’t get it) He desires closeness and intimacy, but he is isolated. He lacks social contacts and networks. He feels others are restricting social contacts. He sees potential in young people. He is single because of introvertism and mostly because of his small social circle. He estimates he could have partnerships and sex. Strong desire for a partnership, it’s nice when you think of someone in the morning. There is an emotional need for closeness. FEELING INADEQUATE FOR A RELATIONSHIP DESIRE FOR PARTNERSHIP AND SEXUALITY, BUT NO SOCIAL NETWORK YOUNGER ADULT YOUNGER ADULT MIDDLE ADULT LONG-TERM PARTNERSHIPS WHICH HAVE DIFFICULTIES IN PARTNERSHIP AND / OR SEXUAL I would like to salvage the partnership. He estimates that he has opportunities for a relationship and sexuality, but he is hindered by physical and physiological problems. Partner is seeking or becomes involved in another relationship. Loss of social network and societal roles feels in a subordinate position. FEELINGS OF POWERLESSNESS AND INEQUALITY IN PARTNERSHIP DESIRE TO BE IN A RELATIONSHIP, BUT FEELING UNABLE TO HAVE A PARTNERSHIP – DISSOLUTION OF THE PARTNERSHIP DISSATISFACTION IN RELATIONSHIP MIDDLE ADULT MIDDLE ADULT MIDDLE ADULT MIDDLE ADULT SUCCESSFUL PARTNERSHIPS AFTER ABI The couple is intimately connected. Partner does not feel like a burden. The couple is not sexually active but has sexual fantasies. Pair is sexually active, she is aware of how much she has endured due to his injury. Sexuality is as before the injury. She appreciates and helps her partner. DENIAL OF GRAVITY OF SITUATION AND ACTUAL FUNCTIONING, LACK OF INSIGHT CHANGE OF SOCIAL ROLES, RELATIONSHIP IS EVEN BETTER THAN BEFORE ABI PROFESSIONAL HELP IN PARTNERSHIP LATE ADULT MIDDLE ADULT MIDDLE ADULT

CATEGORY

Disclosure of persons with ABI

The psychologist’s summary is based on a diagnostic interview

Age period

He lacks social interaction, has no friends, and has trouble establishing communication. In social situations he has prejudices. Trouble expressing himself verbally is preventing him from leading a normal life. He is afraid of the obligations he is supposed to have as a partner, such as financial obligations or forgetting something that his partner would trust him with.

DESIRE FOR PARTNERSHIP, SEXUALITY, AND AGREEMENT THAT HE WILL NOT HAVE A PARTNER BECAUSE OF ABI

YOUNGER ADULT

Not much has changed. He misses sexuality, communication, and tenderness. He has sexual fantasies.

WITH AN INCREASE IN COMMUNICATION, SEXUAL ACTS COULD HAPPEN

LATE ADULT

RRF

M

SD

Enjoyment

4,14

0,967

Success

4,17

1,266

Reciprocity

4,11

1,173

Respect

4,25

1,164

Spl. Satisfaction

4,16

1,112

In present case study, the quantitative results do not match the qualitative results. Qualitative results were based on answers disclosed during the interviews. Possible misunderstandings of delicate questions included in the questionnaire are not excluded. Relationships after ABI are challenging, yet despite the difficulties, people after ABI are very happy in the partnerships. The questionnaire was answered by 75% of the participants that are in currently in partnership. People with ABI are on average very happy with their partner and feel worthy and unique with their partner. On average, they are happy in a relationship that meets their needs.

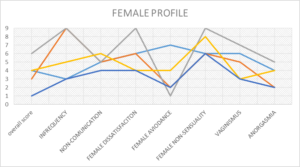

GRISS FEMALE

M

SD

INFREQUENCY

4,50

2,43

NON-COMMUNICATION

4,00

0,7

DISSATISFACTION

9,80

3,83

AVOIDANCE

2,40

2,79

NON-SENSUALITY

6,00

3,08

VAGINISMUS

4,40

2,61

ANORGASMIA

6,00

3,08

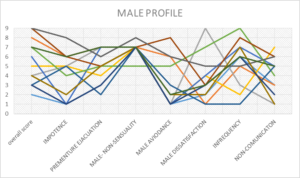

GRISS MALE

M

SD

IMPOTENCE

4,25

3,82

PREMENTURE EJACUATION

5,25

2,67

NON-SENSUALITY

6,00

3,08

MALE AVOIDANCE

2,50

3,08

DISSATISFACTION

5,75

4,05

INFREQUENCY

4,50

2,43

NON-COMMUNICATION

3,00

2,00

Individuals with ABI have intimacy issues in the areas of sensuality, dissatisfaction, and premature ejaculation. On average, women are most dissatisfied with the duration of foreplay, sexual intercourse, and orgasm.

Figure 1: Male GRISS profile.

58.33% of people with ABI generally report dissatisfaction (with ≥5), 50% report impotence problems, 50% report premature ejaculation problems, and 58.33% report irregular sex. All participants report problems with cuddling.

Picture 2: Female GRISS profile.

60% of participants have problems with dissatisfaction and vaginismus. 100% of them have problems with sensuality and affection. In the survey, all men and women (100%) perceive the most problems with intimate contact.

Problems or Absence in Partnership

Problems or Absence of Sex

loss of interest for partnership

loss of interest in sexuality

growing apart and loss of common ground

absence of sexuality due to exhausted partner

uninjured partner has total control

absence of sex due to the consequences of abi(tiredness,etc.) of the injured

dissolution of the partnership

sexual inability

partner with abi feels subordinate

physiological changes, mental, emotional, and cognitive status of the affected

partner without abi is overwhelmed

emotional exhaustion of both partners

exhaustion of the partner caring for the injured

fantasies and obsession with sexuality despite persistent feelings of powerlessness

cheating on a partner with abi

problems with intimacy

cheating of partner with abi

vaginismus

inability to form a partnership due to lack of social contacts

dissatisfaction

having no previous experience with partnerships

impotence

bad self-image

premature ejaculation

desire for partnership and sexuality, but without insight on where to meet partner

sexual dysfunctionin men

partner with abi is jealous of their partner

Conclusion Recommending counseling and psychotherapy (recognizing emotions in relationships, empathy, learning about being a responsible and socially acceptable partner and sexual partner). Help in accepting changed and new social roles and relationships in the family. Teaching socially appropriate behavior. individuals with ABI are taught to regulate their internal impulses. Encouraging counseling and psychotherapy (recognizing emotions in relationships, empathy, learning about responsible sexual behavior, and being a responsible and socially acceptable partner). Learning individuals with ABI to regulate their internal impulses and socially appropriate behavior. People with ABI are made aware of the right to freely choose potential partners to prevent abuse. Implementation of health education – we educate individuals with ABI on safe sex, and the use of protection against pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Introducing possible alternative ways of meeting needs with alternative methods. Providing advice on partnership and sexuality, based on information the individuals with ABI wishes to obtain. (Vešligaj Damiš, Korošec, 2019. Advice on the safe use of online dating portals. Advising the uninjured partner. Involvement of both partners in the counseling process. Discuss sensitive topics in a professional support group with a psychiatrist. Support and advice employees in specific situations. Prevention and intervention to help ensure appropriate behavioral responses. Prevention and intervention to help ensure appropriate behavioral responses. Possibility of educating individuals with ABI on a certain topic and passing of knowledge to colleagues. Supervision. Focusing on assistance from external professional services

AIMED AT PERSON WITH ABI

PREVENTIVE ACTION

ADVICE TO THE PARTNER OF THE INJURED PERSON

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM PARTICIPATION

SECOND AID

In the process of rehabilitation after ABI, areas of partnership and sexuality are among the most demanding, both for people with ABI, professionals, and researchers. We estimate that people with ABI lack insight into their abilities or conceal their inabilities in the areas of sexuality and partnership. It is observed that men more often conceal their abilities and competencies in the field of sexuality and partnership due to ego states and social roles. The research concludes the development period does not affect partnership and/or sexuality. In participants of this study, achieving developmental tasks in the development period was impacted by ABI.\

A good, therapeutic, supportive work alliance that cultivates a high level of trust from individuals with ABI was and is required. Psychologist who processes, researches, and interprets these most sensitive topics, respecting the dignity of fellow humans, while obtaining information in qualitative research, helps individuals with their rehabilitation journey.

References

- Vešligaj Damiš, J. in Korošec, M., (2019) Pridobljene možganske poškodbe: Dolgotrajna rehabilitacija oseb s pridobljeno možgansko poškodbo v doživljenjskem obdobju; Strokovne podlage za nacionalne smernice in standarde storitev. Maribor : Center Naprej / Center Korak.

- Hammond MF, Christine SD, Whiteside OY, Philbrick P, Hirsch AM (2011) Marital Adjustment and Stability Following Traumatic BrainInjury: A Pilot Qualitative Analysis of Spouse Perspectives. Head Trauma Rehabilitation 26: 69-78.

- Oddy M (2010) Sexual relationships following braininjury, Sexual and Relationship Therapy 16: 247-259.

- Downing M, Ponsford J (2016) Sexuality in individuals with traumatic braininjury and theirpartners, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 28: 1028-1037.

- Gill CJ, Sander AM, Robins N, Mazzei DK, Struchen MA (2011) Exploring experiences of intimacy from the view poin to find ividuals with traumatic braininjury and their partners. Journal Head Trauma Rehabilitation 26: 56-68.

- Merc R (2011) Spolnost in seksualne težave po pridobljeni možganski poškodbi. Ljubljana: Zavod za varstvo in rehabilitacijo po poškodbi glave Zarja retrived from: https://www.rtvslo.si/zdravje/partnerstvo-in-spolnost-po-mozganski-poskodbi/252250

- Kreuter MA, Dahlloer g, Gudjosson g, Sullivan M, Sioesteen A (1997) Sexual adjustment and its predictors after traumatic braininjury. Braininjury 12: 349-368.

- Miller L (1994) Sex and the brain-injured patient: Regaining love, pleasure and intimacy. Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation 12: 12-20.

- Horn LJ, Zasler ND (1990) Neuro anatomy and neurophysiology of sexual function. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 5: 1-13.

- Eriksson G, Tham K, Fugl-meyer AR (2005) Couples’ happiness and its relationship to functioning in every day life after braininjury. Scandinavian Journal of OccupationalTherapy 12: 40-48.

- Grahame Simpson G, Cann MCB (2003) Case study Treatment of premature ejaculation after traumatic braininjury. Braininjury 17: 723-729.

- Sander A M, Maestas KL, Pappadis MR (2012) “Sexual functioning 1 year after traumatic brain injury: findings from a prospective traumatic brainin jury model systems collaborative study,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 93: 1331-1337.

- Imes C (1983) Rehabilitation of the head injury patients. Congnitive Rehabilitation 6: 11-19.

- Ducharme S, Gill KM (1990) Sexual values, training and professional roles. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 5: 38-45.

- Bele S, Svetina M (2011) Komunikacija, reševanje konfliktov in zadovoljstvo s partnerskim odnosom : diplomsko delo, Ljubljana.

- Aloni A, keren O, Cohen M, Rosentul N, Romm M, et al. (1998) Incidence of sexual dysfunction in TBI patients during the early post-traumatic in-patient rehabilitation phase. BrainInjury 13: 89-97.

- Burridge CA, Williams HW, Yates JP, Harris A, Ward C (2007) Spousal relationship satisfaction following acquired braininjury: The role of insight and socio-emotional skill, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. An International Journal 17: 95-105.

- Garden FH, Bontke CF, Hoffmann M (1990) Sexual functioning and marital adjustment after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 5: 52-59

- Kreutzer JS, Marwitz JH, Hsu N, Williams K, Riddick A (2007) Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Virginia Common wealth University, Richmond. Neuro Rehabilitation 22: 53-59.

- Pistoia F, Govoni S, Boselli C (2006) Sex after stroke: a CNS only dysfunction?. Pharmacol Res 54: 11-18.

- Ponsford JL, Olver J H, Curran C (1995a) A profile of outcome two years following traumatic braininjury. BrainInjury 9: 1-10.

- Ponsford J (2003) Sexual changes associated with traumatic braininjury, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: An International Journal 13: 275-289. DOI: 10.1080/09602010244000363

- Yurdakul KL, Wood R L (1997) Change in relationship status following traumatic braininjury. BrainInjury 11: 491-502.