Publication Information

ISSN 2691-8803

Frequency: Continuous

Format: PDF and HTML

Versions: Online (Open Access)

Year first Published: 2019

Language: English

| Journal Menu |

| Editorial Board |

| Reviewer Board |

| Articles |

| Open Access |

| Special Issue Proposals |

| Guidelines for Authors |

| Guidelines for Editors |

| Guidelines for Reviewers |

| Membership |

| Fee and Guidelines |

|

Challenges Faced By Anganwadi Centres in Delivering Nutritional Meals to Pregnant Women, Lactating Mothers and Children in Mumbai during COVID-19

Deepshikha K Mishra1 & Navjit Gaurav2 *

1School of Health System Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India

2School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen’s University, Canada

Received Date: February 23, 2022; Accepted Date: March 02, 2022; Published Date: March 08, 2022;

*Corresponding author: Navjit Gaurav. School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen’s University, Canada. Email: 19ng7@queensu.ca

Citation: Mishra D K, Gaurav N (2022) Challenges Faced By Anganwadi Centres in Delivering Nutritional Meals to Pregnant Women, Lactating Mothers and Children in Mumbai during COVID-19. Adv Pub Health Com Trop Med: APCTM-145.

DOI: 10.37722/APHCTM.2022301

Abstract

In India, Anganwadi Centers (AWCs) under Integrated Child Development Scheme covers 84 million children under six years of age and 10.9 million pregnant women and lactating mothers. Covid-19 lockdown led AWCs to shut down their in-person services in many states, putting the growth and development of beneficiaries at stake. This study explored how COVID-19 hampered the nutritional health of beneficiaries and increased the risk of disability prevalence due to the dysfunctionality of AWCs in Mumbai’s informal settlements. A qualitative approach that involved semi-structured, audio-recorded telephone interviews was conducted with fifteen Anganwadi workers, in Hindi. Concurrently with data collection, each interview was transcribed verbatim. We used Braun and Clark’s six steps thematic analysis to analyze the data. The themes around the challenges faced by AWCs in service delivery were extracted. Themes were described and substantiated by the actual quotes of the participants. Five core themes were identified: irregular growth assessment and monitoring, limited access to rehabilitation services, disrupted food supply and substandard food quality, limited parental involvement/care, and curbed support from partnering organisations. This study will help in devising mitigation strategies to avert the possible negative consequences of COVID-19 led AWCs closure, on beneficiaries’ health. Considering the AWCs play a vital role in early identification, promotion of development, disability prevention, and children’s well-being, the challenges in its service delivery should be addressed with priority.

Keywords: Anganwadi Center; Children; COVID-19; Disability; India; Nutritional Health

Introduction

Initially, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID‐19 as a public health emergency and later a pandemic (WHO, 2020). COVID-19 had a cascading impact on various sections of society and the economy at different levels due to lockdown (Lenzen et al., 2020). UNICEF highlights that the repercussions of the pandemic are causing more harm to children than the disease itself (UNICEF, 2020). For instance, globally an additional 6.7 million children under the age of five could suffer from wasting and therefore become undernourished in 2020 (Unitlife, 2021). As per the Global Nutrition Report (2020), India is home to half of the world’s malnourished children. Over 40 million children are chronically malnourished and wasted in India. Malnourishment leads to stunting, developmental delays, and childhood disability (De & Chattopadhyay, 2019). This has been aggravated further because of the pandemic.

Early childhood rehabilitation and intervention are vital to prevent the onset of disability (Basantia & Alom, 2020). AWCs, a community-based institution under India’s Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) works for disability prevention, early identification, and promotion of rehabilitation benefits for children (Basantia & Alom, 2020). As part of the ICDS, women, and children are provided with hot cooked meals and takeaway home rations in AWCs (Gupta, 2020). Under the supplementary nutrition programme, children (6 months-6 years) and pregnant & nursing women are the beneficiaries. The Indian government reports that the ICDS programme covers 84 million children below 6 years of age and 10.9 million pregnant women and lactating mothers under AWCs (Basantia & Alom, 2020). Covid-19 led AWCs to shut down their in-person services in many states, putting the growth and development of beneficiaries at stake. Losing jobs (Estupinan & Sharma, 2020), pay losses (Gopalan & Misra, 2020), and dwindling economics (Lee, Sahai, Baylis, & Greenstone, 2020) forced many families to cut their expenses (Kumar et al., 2020) often at the value of nutritious food, which children may have otherwise had access to.

In overcrowded informal settlements, the measures taken by the Union and state governments to fight COVID-19, like staying at home and following the practice of social distancing, where distances of six feet should be maintained between individuals, were not feasible (Shadmi et al., 2020). Many believe COVID-19 was not a disease of the poor (Dutta, Acharya, Shukla, and Acharya, 2020), however, the number of COVID cases in the informal settlements speaks the truth. The people in the informal settlements were ill-prepared to fight the pandemic, with livelihoods threatened because of the lockdown highlighting inadequacies of human living and its vulnerability in the face of a pandemic (Kumar et al., 2020). A lot of people migrated in and out of the city seeking secured tenure, food, and livelihood leading to a gap in continued access to nutritional food and supplement for early age children (Lee et al., 2020). A Stranded Workers Action Network survey recently conducted across various states showed out of 11,159 migrant workers, 96 percent did not get a ration and 90 percent of them did not get wages (Adhikari, Narayanan, Dhorajiwala, and Mundoli, 2020). In the event of an outbreak of this kind and the associated containment measures, basic deficiencies of the urban poor are overlooked, not just in terms of their inadequate living conditions, but also in terms of their lack of access to healthcare and rehabilitation (Lenzen et al., 2020).

The study context

Mumbai is one of the largest and most populous cities in India with over 42 percent of its population living in informal settlements (TISS, 2015). Informal settlements encompass crosscutting cumulative and complex deficits across multiple generations and cultural identities (Alber, Cahoon & Röhr, 2017). The M-East ward is one of the twenty-four administrative divisions of Mumbai, and it is home to a population of over 8.07 million (Census, 2011). It is one of the poorest wards in the city and scores as low as 0.05 on the Human Development Index (HDI) which is the lowest in the city. Nearly 72.5% of the total population of the M-East ward lives in informal settlements. Moreover, according to the Human Development Report 2009, this area has an infant mortality rate of around 66.47 per thousand live births and more than 50 percent of children are malnourished (Klugman, 2009).

Problem statement

The Coronavirus crisis has presented us with unprecedented challenges and the impact will be felt for some time to come (Cullinane & Montacute, 2020). India, like many other countries, had gone into a nationwide lockdown to manage the spread of COVID-19. The lockdown has resulted in many vulnerable groups and communities struggling to find two square meals per day. These include pregnant women and lactating mothers, children, daily wage labourers, migrant workers, pavement dwellers, the homeless, the destitute, and other urban households in informal settlements. The situation demands immediate response to ensure a continued supply of nutritious meals to these vulnerable groups. This study explored the following questions-

- What are the challenges faced by Anganwadi centers during the COVID-19 lockdown in the supply of nutritional meals to the beneficiaries?

- How does the dysfunctionality of Anganwadi centres affect the beneficiaries?

The theoretical underpinning of this study

COVID-19 and its consequences on the physio-psycho-social wellbeing of children and families living in informal settlements could create a devastating community imbalance (Corburn, 2020). People living in these settlements are affected by widespread poverty, unemployment, poor public health, and poor civic and educational standards (World social report, 2020; DESA, 2020) that affect the health and wellbeing of children. Moreover, the women living in these settlements have been exposed to societal negligence (Unger, 2013), dependency on others (Osrin et al., 2011), limited opportunities to participate (Unger, 2013), and have poor access to healthcare facilities (Corburn, 2020). With this understanding of women and children’s living conditions in informal settlements, we propose that the aforementioned societal challenges cultivate a disabling environment prone to poor health outcomes.

Method

Study Design

We employed an exploratory qualitative study based on telephonic in-depth interviews using semi-structured questions which were suited to the exploratory aims of the study (Pope and Meys, 1995). This design has several advantages, including its flexibility and ability to provide an in-depth investigation of the attitudes, experiences, and intentions of participants (Boyce & Neale, 2006). The interviews were conducted among the Anganwadi workers to explore the effect of COVID-19 induced lockdown on the supply of nutritional food to the beneficiaries by AWCs. We used an interview guide to ensure all participants were asked some core questions while allowing for flexibility on how to approach novel information (Barriball and white, 1994). Furthermore, the interviewer also had the freedom to probe the participants to elaborate on the original response or to follow a line of inquiry introduced by the participant (Fox, Hunn & Mathers, 2009).

Participants and procedures

The sample frame for this study included Anganwadi workers of the M-East ward, Mumbai. Anganwadi workers are community-based front-line workers of the Indian government’s Integrated Child Development Services Programme, who play a crucial role in promoting child growth and development (Journals of India, 2020). Being an agent of social change, they mobilize community support for better care of young children (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2021). Fifteen Hindi-speaking Anganwadi workers with a minimum working experience of 10 years participated in this study. Participants were purposely recruited (Rai and Thappa, 2015), the purpose of recruiting the participants with 10 years of experience was to ensure they have concrete community work experience and had the experience of working amidst Covid-19 lockdown. Once data saturation was reached after 15 interviews (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson, 2006), no further participants were recruited.

Data collection

The data collection employed in-depth interviews with the Anganwadi workers. The interviews took place between April and June 2021 over the telephone. The interviews ranged from 45 to 60 minutes and were audio-recorded. The interviews were conducted in Hindi using an interview guide with open-ended questions. The interview was conducted by both the researchers (DKM and NG) who had previous experience in conducting telephone interviews. NG holds a master’s degree in social work with a specialisation in disability studies and action, while DKM is pursuing a master’s in public health. The interview guide was piloted on the first two participants. After the pilot, we modified the interview guide focussing more on the supply of nutritional food, challenges in accessing support from partnering organizations, and door-to-door delivery of services. An interview guide is included in (box 1). For all interviews, participants were asked to first provide a brief account of their working experience with children during COVID and then discuss the supply and access of nutritional food to pregnant women and lactating mothers. Participants were given a study information sheet shared through WhatsApp before the interview for them to make an informed choice before participating in the study. Once they agreed to participate, the interview was scheduled at their convenient time. The researchers read the information sheet again before initiating the interview and asked for their verbal consent to audio record the interview. Interviews were conducted once informed verbal consent was obtained from the participants.

Box 1: Interview guide

1. Could you tell me about your work?

2. How has COVID impacted your work at the AWCs? Probe:

· Regular assessment of children? (Prompt: weight, height, etc)|

· Supply of nutritional food to the children and mothers.

· Nutritional supplement for children?

· Check-up of pregnant women.

3. Healthcare referral during COVID-19. (Therapy- speech, physio, occupational- developmental delay)

4. Do you have any children with disabilities at your Anganwadi?

5. What kind of work do you do for children with disabilities?

6. Can you describe the preventive measures taken for children with/out disabilities during COVID-19?

7. If there were growing health concerns for pregnant women and lactating mothers in your working area, what were the measures taken by AWCs?

8. Can you describe your experience of coordinating with the partner organizations to support rehabilitations therapies for children during lockdown?

9. Have the government/you adapted any strategy to deal with supplying food to the families during lockdown?

10. What challenges did you face while supplying food to the children and mothers during the lockdown?

11. How has migration of families impacted the track and assessment of children's growth?

Data Analysis

Concurrently with data collection, each interview was transcribed verbatim in the original language (Hindi) for primary analysis to minimize error and meaning loss (Zhu, Duncan, and Tucker, 2019; Oxley et al., 2017). All the interview transcripts were organized in Atlas Ti software before analysis. The authors further used Atlas Ti to generate initial codes and later core themes. Interview transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis and the researchers followed six steps of thematic analysis by Braun and Clark (2006) for qualitative research. Both the researchers (DKM and NG) independently read the transcripts a couple of times to get versed with the data and noted the initial codes. Transcripts were parallelly coded by DKM and NG and the initial coding process involved highlighting compelling excerpts in the data. After the first three transcripts both the researchers sat together and discussed the coding process and emergent themes were highlighted. A codebook was developed for coding the remaining transcripts based on the discussion. This peer-debriefing (Scharp & Sanders, 2019) provided the researchers with an idea about the emerging themes and the same process was followed for the remaining transcripts. Once the coding was done, the codes were grouped with similarities and differences into potential themes and checked if the themes work in relation to the coded excerpts. This process was followed by refining the specifics of each theme independently by both the researchers and naming them. Any other relevant statements were given new codes at every stage, which culminated in the final coding and sub-themes. The subthemes were grouped to form core themes (box 2). The themes around the challenges faced by Anganwadi workers in service delivery and possible repercussions on children and lactating mothers’ health were extracted. Themes also included the effect of delayed or no access to nutritional food leading to the onset of the disability and continued challenges for the family members and caregivers. Themes were described and substantiated by the actual quotes of the participants.

Once the core themes were identified, the authors who are bi-lingual (Hindi and English), translated the core themes and supporting quotes from Hindi to English initially and looked for the meaning, then again back-translated the themes and quotes from English to Hindi after initial modification in the core themes. The process of translation and back translation (Chen & Boore, 2010) helped in ensuring richness of the data and data accuracy. Once the meaning and actual essence of the core themes and quotes were established these were finally back-translated from Hindi to English.

Results

Fifteen Anganwadi workers participated in the study (Table 1). The average years of working experience of recruited participants were 11 years and their average age was 34 years. All the 15 participants were female. Considering inclusion criteria, all 15 participants had the experience of working amidst Covid-19 lockdown. 10 participants had a year or more than a year of working experience during Covid-19 lockdown while that of 2 participants ranged from 6 months to 1 year and 3 participants experienced the same for 6 months.

| Table 1: Participants’ characteristics | |

| Number of participants (n) and gender | 15; Female |

| Average years of working experience (years) | 11 years |

| The average age of the participants | 34 years |

| Working experience amidst COVID-19 6 months 6 months to 1 year 1 year and more |

(n=number of participants) 3 2 10 |

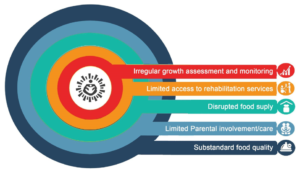

The challenges faced by the AWCs in supplying nutritional meals to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children in Mumbai during COVID-19 are depicted in Figure 1 below. The five core themes are identified from the data that highlights the challenges faced by AWCs while providing services amidst COVID-19 in Mumbai. The core themes included irregular growth assessment and monitoring, limited access to rehabilitation services, disrupted food supply and substandard food quality, limited parental involvement/care, and curbed support from partnering organisations.

Box 2: Key themes and sub-themes

Irregular growth assessment and monitoring

A. Disrupted assessment and monitoring

B. No access to therapies.

Limited access to rehabilitation services

A. No regular follow-up of rehabilitation services

B. No monitoring processes.

C. Curbed support from partnering organisations

Disrupted food supply

A. Limited or no contact with families impeding the service delivery

B.Door-to-door delivery at a later stage

C. Irregular supply of nutritional food

D. Discontinued supplement (Iron folic, Vitamins etc)

Substandard food quality

A. Compromised quality of food

B. Local adaptations/alternatives for food supplements

C. Discontinued supplement (Iron folic, Vitamins etc)

Limited parental involvement/care

A. Limited avenues for parental counseling and knowledge dissemination.

B. Parental involvement and care became determining factors for children’s overall growth

Figure 1: The challenges faced by the AWCs in supplying nutritional meals to pregnant women, lactating mothers and children in Mumbai during COVID-19.

Irregular growth assessment and monitoring

The dysfunctionality of AWCs resulted in irregular growth assessment and monitoring of the beneficiaries. Children who might have benefitted from the regular assessment at AWCs were kept aloof from need-based rehabilitation intervention. Anganwadi workers adopted selective measurement and assessment of children who were malnourished amidst COVID-19. One of the respondents while discussing the effect of lockdown mentioned:

“In Covid lockdown, we started taking weights of only malnourished and medium malnourished children through home visits. As parents stopped bringing their wards to Anganwadi centres, we could not keep a track of every child.” - (AWW4)

Moreover, the supply of daily midday meals (nutritionally balanced food) that was earlier provided to the children has stopped due to lockdown and was replaced with a ration kit. Children's diets at home are not being assessed and the children are left at the mercy of the caregivers to either feed them with the required portion or feed the entire household with the same ration kit. One of the respondents mentioned:

“Midday meal is replaced by ration containing wheat, oil, turmeric, gram, salt, and sugar. But now it depends on the parents how much they feed it to their wards, we have no track of it. Sometimes, they are using the same ration kit to feed the family”- (AWW6)

Moreover, respondents highlighted that COVID-induced lockdown and disrupted livelihoods in the informal settlements forced many families to migrate to their villages, affecting routine health check-ups, growth assessments, and nutrition supply by Anganwadi workers to the beneficiaries. As a result, the tracking of growth and development of children by AWCs was missed, and it was not possible to stay connected online when the families moved to their respective villages. Irregular growth and assessment also resulted from the limited awareness among the Anganwadi workers to work with the children with disabilities and their families during COVID-19 lockdown in low-resource urban settings, as the public health guidelines kept changing frequently (Bhaumik et al., 2020; Sen & Seth, 2021).

Limited access to rehabilitation services

COVID-19 also limited the access to the therapeutic interventions and facilities that the children might have access to earlier. The organizations which were working in partnership with the AWCs to provide immediate and timely rehabilitation services were also shut down or limited their in-person services in the wake of the COVID-19 spread. As a result, the major support the AWCs might have had was taken away and they were left to serve the entire community on their own. Due to the limited availability of these rehabilitation services, the children are prone to disability and are left with no other option than to live in a disabling home condition. One of the respondents actively involved in connecting the children with therapy mentioned-

“Children would earlier go to Anganwadi centers, therapy sessions, parks, etc. Now they just sit at home. This has led to regression among children.”- (AWW1)

When enquired about the possible consequences of limited or interrupted access to rehabilitation services to children, one of the respondents added that the child may develop limited movement due to tightened muscles, the child could experience limited gross and fine motor skills, they might not develop social skills, and this limits their physio-psycho-social growth.

The inhibited accessibility to counseling has also affected the mothers and their childcare. Another respondent while discussing access to parental counseling highlighted:

“We have discontinued monthly parental counseling for pregnant women, lactating and all mothers where they were given counseling to take folic acid, calcium tablets to prevent lack of mental growth of children.”- (AWW3)

These counseling services earlier helped them during pre, peri, and postnatal parental care which has been interrupted due to COVID-19. But as a result of lockdowns and public health guidelines, home visits to educate parents with special emphasis on infants are curtailed. Children are therefore facing developmental delays. Limited or no supportive facilities like therapies, counselling through partner organisations or Anganwadi workers were one of the major problems faced by the Anganwadi centers in Mumbai during COVID-19 (Krishnaprasad, 2021). This problem pushed the family (pregnant women & lactating mothers, caregivers) as well as the children to further struggles with maintaining a healthy balance between mental and physical health.

Disrupted food supply

The dysfunctionality of AWCs disrupted the supply of nutritional food. The respondents highlighted that the food pregnant women and lactating mothers might have access to through Anganwadi centres, were missed due to lockdown. As a remedial adaptation during the pandemic, the ration was delivered to beneficiaries’ doorsteps. However, since all instructive communications were being carried out online, children’s dietary intake could not be accurately monitored. One of the respondents highlighted:

“All remedies and solutions to gain weight are being communicated to parents over phone calls now. We cannot be sure if our instructions are being followed.”- (AWW9)

While discussing the availability of nutritional food, one of the respondents highlighted the lack of daily nutritional meals is also affected by the loss of parental employment during COVID lockdown. She mentioned:

“Many parents lost their employment. It has impacted the quantity and quality of daily food supplies of households.”- (AWW15)

The majority of the respondents communicated that woman due to disrupted food supply could face complications during pregnancies and that could affect the child’s growth and development. In addition to food, supply of other supports and facilities like- IFA tablets, sanitary napkins, provision of supplementary nutrition, health education, and implementation of immunization activities are a few of the services to mention which are being hampered due to pandemic (Kumar et al., 2020; Poddar & Mukherjee, 2020). These cumulatively impacted the life and healthcare support to families in Mumbai (Krishnaprasad, 2021).

Substandard food quality

The access to quality food was affected by the COVID lockdown and the beneficiaries have to face challenges with the compromised quality of food. The Anganwadi workers highlighted, families started adapting to local remedies to meet nutritional requirements, but it often lacks the dietary requirement of children and mothers. The regular ration provided for the beneficiaries was now distributed among the entire family. One of the respondents mentioned:

“Although the ration is allotted in the name of the child, now the whole family might consume it. Earlier we used to make sure that the child eats in front of us.”- (AWW10)

Another respondent mentioned:

“It’s been 2 years that the medicine kits/supplements like folic acid have been discontinued. It used to come earlier.”- (AWW2)

Due to partial or complete closure of AWCs, the access to the required supplement (Iron, Folic acid, Vitamins) to the pregnant women and lactating mothers were discontinued. These supplements that provide nutrition to the mothers had stopped being available for more than a year now. The irregularity in the supply of nutritional supplements presented high risk to health for lactating mothers and pregnant women as well as children in the urban low resource settings (Thareja & Singh, 2021; The World Bank, 2020).

Limited parental involvement/care

The lockdown and sudden job loss put the family at the brink of an economic crisis (Estupinan & Sharma, 2020). As a result, the parents and caregivers had to work in odd conditions and hours of the day to earn something for their family. One of the respondents while discussing parental involvement in economic activities and curbed opportunities of parental care highlighted:

“I have seen both parents working during this lockdown for regular income. There is no one at home to take care of the children.”- (AWW7)

As a result of the fight for two square meals, parental involvement and care - which was the family's primary support - is essentially nonexistent. Further due to the dysfunctional AWCs, the children are left on their own or in the care of their siblings who are also young. An absence of special instructors has added new challenges to parenting (Bharadwaz, 2021). Parents often lack the understanding required to teach special kids and not every parent has the luxury of time or the ability to do so, according to experts (Bharadwaz, 2021). When parents are working, there were no one to assist children to eat timely food, watch videos, sitting and study.

“Lack of parental involvement has largely affected the learning and growth of the child. Even parents are tired after coming from work, they are hardly left with any energy to sit with their children and teach them.”- (AWW12)

One of the respondents highlighted the suitability of parental education to be supportive of a child's growth and development. While discussing the challenges for parents of disabled children she mentioned-

“We have to loop in parents, elder siblings and even neighbours. Sometimes parents are not educated enough to understand our instructions. Most of them go out for menial work.”- (AWW12)

Due to limited parental involvement and care, the children are subjected to vulnerabilities, learning loss which they might not have if the AWCs were functional.

Discussion

In this study, we used qualitative methods to explore and develop an in-depth understanding of different factors responsible for interrupted service delivery by AWCs and the way they affected the beneficiary’s health. We found extensive evidence on the dysfunctionality of AWCs that could negatively affect the health outcomes of beneficiaries in Mumbai’s informal settlements amidst COVID-19. The results of this study resonate with the findings of the studies by Basantia and Alom (2020) where they highlight the impact of non-functional AWCS on the health of community children resulting in their stunted growth and malnutrition. This study further discusses the challenges with online instruction and inhibited monitoring of beneficiaries in informal settlements and its impact on the mental and physical health of both children and caregivers, like the findings of a study by Gopalan and Mishra (2020). As a consequence of the dysfunctionality of AWCs, lack of physical interaction with Anganwadi teachers and peers has stunted the socio-emotional development of such children (Bharadwaz, 2021). Additionally, the consequences of limited physical interactions which were earlier possible at the AWCs lead to behavioural disorders and anxiety levels in children at a young age during the lockdown, which is detrimental for children’s physical and mental growth (Zvolensky et al., 2020). The study highlights the limited parental involvement and care and its impact on a child's learning and growth. For instance, educational videos are shared with the parents but not everyone has a WhatsApp or internet connection. Also, most of the time there is no response, sometimes the parents just give affirmative replies to skip the follow-ups. The study provided evidence on the loss of employment and its impact on primary care and support for the beneficiaries at home; how the family has to compromise and adjust to the availability of substandard food. This finding is congruent with the studies done by Estupinan and Sharma (2020) and with Lee and colleagues (2020), where they highlight job loss and its socio-economic impact on the family. Another study on the socio-economic impact of COVID by Kumar and colleagues (2020) discusses similar findings related to the health and care of children and families and the impact on family economics due to COVID.

Further, this study contributes to the understanding of limitations on the access to rehabilitation services to the beneficiaries, and the way it could lead to the onset of childhood disability among them. The lockdown, which lasted more than a year, negatively affected the operations of the Anganwadi and created a disabling environment for children in need to access rehabilitation services like therapies, clinical check-ups (Murthy et al., 2020). Partnering organizations that work in collaboration with AWCs also had limited activities during the pandemic. These findings resonate with a study by Murthy and colleagues (2020) that highlights that 54% of the individuals with disabilities including children reported that they failed to access the rehabilitation services during the lockdown. The majority of them needing rehabilitation services said it was physiotherapy that was compromised during the lockdown (Murthy et al., 2020). Irregularity in the rehabilitation therapies could lead to developmental disabilities and reduced gross motor functions among children with functional limitations (Bult et al. 2011). The study provided major evidence on the way COVID-19 has interrupted the regular growth assessment of children (Basantia & Alom, 2020). Despite door-to-door ration delivery, there is no monitoring of children's nutritional requirements being met daily. Reasons include irregular food supply during the pandemic, substandard quality of food, and local alternative food adaptations to increase the weight of malnourished children (De & Chatopadhyay, 2019). Besides the socio-economic burden caused by the COVID-19 lockdown (Kumar et al. 2020), limited avenues for parental counseling and knowledge dissemination about health also contributed to the negligence towards children’s health. Lack of nutritious and adequate food leads to stunted growth, wasting, and malnourishment in children, further pushing them towards the onset of disability (Murthy et al, 2020; Lee et al., 2020). The hands-on experience was completely lost, and the children were left to the mercy of the caregivers.

As a possible consequence of the dysfunctionality of AWCs for more than a year, children’s physical activity was confined to home. Limited physical activities have impeded the emotional and physical development of children (Kumar et al., 2020). Behavioural disorders among children have been on the rise due to continued isolation from their peers and friends and inhibited physical activities (Zvolensky et al., 2020).

Study limitations

Our study aimed to explore Anganwadi workers’ experience in providing nutritional food and rehabilitation services in Mumbai’s informal settlements. Our study participants were from one of the most underprivileged wards of Mumbai and might have limited access to nutritional food and rehabilitations services for pregnant women and lactating mothers, or children with disabilities. It is worth considering the extent to which study findings could be generalised to other parts of Mumbai or India where the level of Anganwadi services could be lower or higher during the COVID-19 lockdown. Due to the widespread pandemic, telephone interviews were chosen as the method of data collection. There are fair chances of missing visual and non-verbal cues in the telephone conversations, which could have substantiated and added to the richness of data.

Conclusion

The study highlighted the challenges in the supply of nutritional food and rehabilitation services by the AWCs and its possible consequences on the health of women and children. Understanding the challenges in ensuring a continued supply of nutritious meals to vulnerable groups is a crucial step in devising mitigation strategies to avert the negative consequences of COVID-19 on children’s health and protect the onset of childhood disability. To prevent the onset of disability, it is important to have regular health assessments, easy access to rehabilitation services, and ensure avenues to engage with local organisations. Given that the Anganwadi workers play a vital role in disability prevention, early identification, promotion of development, and well-being of children, the challenges in service delivery should be prioritised. Social policy and government must ensure emphasis on bridging the gap for continued access to nutritional food and supplement for early-age children created during the Pandemic. COVID-19 lockdown has allowed servicing providers and policymakers to identify and analyse the weak links and bottlenecks for any such unforeseen circumstances in the future. Fact because the majority of AWCs were closed during the lockdown, the role of parental involvement has become all the more important in the overall development of children. Study findings could help in exploring ways parents could be counseled over the importance of a balanced diet, maintenance of sanitation and hygiene, referral care provisions, and provide technical assistance to facilitate online learning for children.

Acknowledgments

We extend our deep gratitude to all the Anganwadi workers of M-East ward, Mumbai who provided us with wonderful insights about the challenges they faced by AWCs in service delivery to the community amidst COVID-19.

References

- Adhikari A, Narayanan R, Dhorajiwala S & Mundoli S (2020). 21 days and counting: COVID-19 lockdown, migrant workers, and the inadequacy of welfare measures in India. A report by the stranded workers action network.

- Alber G, Cahoon K & Röhr U (2017). Gender and urban climate change policy: Tackling cross-cutting issues towards equitable, sustainable cities. Routledge.

- Anganwadi Services Scheme. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2021, from Nic.in.

- Averting a lost COVID generation. (n.d.). Retrieved September 30, 2021, from Unicef.org.

- Barriball K L & While A (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: a discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19:328-335.

- Basantia T K & Alom J H (2020). Rehabilitation Mechanisms for Special Group Children: A Study of Anganwadi centres under Integrated Child Development Services Projects. Rehabilitation, 7(18).

- Bhaumik S, Moola S, Tyagi J, Nambiar D & Kakoti M (2020). Community health workers for pandemic response: a rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 5:e002769.

- Boyce C & Neale P (2006). Conducting in-depth interviews: A guide for designing and conducting in-depth interviews for evaluation input.

- Braun V & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3:77-101.

- Bult M K, Verschuren O, Jongmans M J, Lindeman E & Ketelaar M (2011). What influences participation in leisure activities of children and youth with physical disabilities? A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32:1521-1529.

- Census of India. (2011). Census of India website: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from Gov.in.

- Chen HY & Boore J R (2010). Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing research: methodological review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19:234-239.

- Corburn J, Vlahov D, Mberu B, Riley L, Caiaffa W T, et al. (2020). Slum health: Arresting COVID-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 97:348-357.

- COVID-19: School closure takes a toll on differently abled kids, say experts. (n.d.). Retrieved September 30, 2021, from Org.in.

- Cullinane C & Montacute R (2020). Research Brief: April 2020: COVID-19 and Social Mobility Impact Brief# 1: School Shutdown.

- De P & Chattopadhyay N (2019). Effects of malnutrition on child development: Evidence from a backward district of India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 7:439-445.

- Desa U (2020). World social report 2020: Inequality in a rapidly changing world. New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

- Dutta S, Acharya S, Shukla S & Acharya N (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic-revisiting the myths. SSRG-IJMS, 7:7-10.

- Estupinan X & Sharma M (2020). Job and wage losses in the informal sector due to the COVID-19 lockdown measures in India. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Fox N, Hunn A & Mathers N (2009). Sampling and sample size calculation. East Midlands/Yorkshire: the National Institutes for Health Research. Research Design Service for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber.

- Gopalan H S & Misra A (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and challenges for socio-economic issues, healthcare and National Health Programs in India. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome, 14:757-759.

- Gupta S (2020, November 28). In a first, anganwadi kids, and pregnant and lactating women in Odisha receive fish as part of their diet - Gaon Connection. Retrieved October 15, 2021, from Gaonconnection.com.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18:59-82.

- Hayat K, Rosenthal M, Gillani A H, Zhai P, Aziz M M, et al. (2019). Perspective of Pakistani physicians towards hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs: A multisite exploratory qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16:1565.

- Krishnaprasad S (2021). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Case of Anganwadi and ASHA Workers with Special Reference to Maharashtra. In Gendered Experiences of COVID-19 in India(pp. 77-99). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Klugman J (2009). Human development report 2009. Overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development. UNDP-HDRO Human Development Reports.

- Kumar S, Maheshwari, Prabhu, Prasanna, Jayalakshmi, et al. (2020). Social economic impact of COVID-19 outbreak in India. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, 16:309-319.

- Kumar M M, Karpaga P P, Panigrahi S K, Raj U, Pathak V K (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent health in India. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 9:5484.

- Lee K, Sahai H, Baylis P, Greenstone M (2020). Job loss and behavioral change: The unprecedented effects of the India lockdown in Delhi. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Lenzen M, Li M, Malik A, Pomponi F, Sun YY, et al. (2020). Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PloS One, 15:e0235654.

- Manifest Team. (2020, June 16). Anganwadi workers. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from Journalsofindia.com.

- Murthy G V S K, S, L M G, Sadanand S, Tetali S, CBM India Trust F, et al. (2020). A Strategic Analysis of Impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities in India. Hyderabad, India.

- Osrin D, Das S, Bapat U, Alcock G A, Joshi W, et al. (2011). A rapid assessment scorecard to identify informal settlements at higher maternal and child health risk in Mumbai. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 88:919-932.

- Oxley J, Günhan E, Kaniamattam M, Damico J (2017). Multilingual issues in qualitative research. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 31:612-630.

- Poddar P, Mukherjee K (2020). Response to COVID 19 by the Anganwadi ecosystem in India. KPMG.

- Pope C, Mays N (1995). Qualitative Research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ, 311:42-45.

- Rai N, Thapa B (2015). A study on purposive sampling method in research. Kathmandu: Kathmandu School of Law.

- Sen A, Seth S (2021). Problems and Potentials of Anganwadi Workers in the ICDS Projects: An Empirical Study. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 12:474-477.

- Scharp K M, Sanders M L (2018). What is a theme? Teaching thematic analysis in qualitative communication research methods. Communication Teacher, 33:1-5.

- Thareja A, Singh A (2021). Community Health Workers: The COVID Warriors of Rural India. International Journal of Policy Sciences and Law. 1:60-73.

- The World Bank IBRD IDA. (2020, April 27). India: The Dual Battle Against Undernutrition and COVID-19 (Coronavirus). The World Bank.

- TISS (2015). Socio-Economic Conditions and Vulnerabilities: A Report of the Baseline Survey of M(East) Ward, Mumbai. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Accessed on (July 21, 2021).

- Unger A (2013). Children’s health in slum settings. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98:799-805.

- Zhu H, Duncan T, Tucker H (2019). The issue of translation during thematic analysis in a tourism research context. Current Issues in Tourism, 22:415-419.

- Zvolensky M J, Garey L, Rogers A H, Schmidt N B, Vujanovic A A, et al. (2020). Psychological, addictive, and health behavior implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 134:103715.