Intercultural Competence Assessment: Insights and Recommendations for Current Chinese Language Teaching in Public Schools of the UAE

Shan Jin*, Abdulai Abukari

1 Chinese Language Teacher at the Emirates Schools Establishment and EdD Student in Education at the British University in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2Professor at the British University in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Received Date: May 19, 2024; Accepted Date: May 25, 2024; Published Date: June 21, 2024;

*Corresponding author: Shan Jin, British University in Dubai enrolled on a Doctor of Education programme. Email: 22000300@student.buid.ac.ae

Citation: Jin S, Abukari A (2024) Intercultural Competence Assessment: Insights and Recommendations for Current Chinese Language Teaching in Public Schools of the UAE; edu dev in var fields EDIVF-121

DOI: 10.37722/EDIVF.2024101

Abstract

This study explores the application and evaluation challenges of intercultural competence within Chinese language education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), employing a methodology that includes a literature review, keyword search analysis, and comparative analysis. Initially, it conducts a comprehensive review of various intercultural competence models, linking them to language proficiency and proposing an evaluative framework. Through a keyword search focused on “culture” and “intercultural,” the paper summarizes the Chinese language teaching framework in UAE’s public schools, assessing how intercultural competence is integrated and highlighting the gaps in current assessments. A comparative analysis then scrutinizes the intercultural communicative competence requirements in the UAE’s Chinese language curriculum against established models, identifying challenges and discrepancies. This methodology enables a deep dive into the methods used to develop and assess intercultural understanding among students, addressing the subjective nature of evaluation techniques and the limitations due to students’ language skills. Moreover, the study examines the complexities of embedding cultural insights into language instruction, tailored to the UAE’s distinct educational landscape. The conclusion advocates for a multifaceted assessment approach, merging diverse tools and strategies to enhance evaluation effectiveness and fairness. By proposing improvements for intercultural competence assessment in the Chinese language curriculum, this study aims to align evaluations more closely with educational goals, facilitating a comprehensive and meaningful assessment of students’ intercultural competence, thus contributing significantly to the field of language education and intercultural understanding.

Keywords: Intercultural Competence Assessment, Chinese Language Teaching in the UAE, Curriculum Analysis, Assessment Challenges

Introduction

Background

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), a federation composed of seven emirates, is renowned for its diversity, abundant resources, and strategic geographical location. As an international business hub, the UAE has attracted professionals and entrepreneurs from around the world. Particularly in the context of globalization, the implementation of a multilingual policy has strengthened its position as a center for international trade and cultural exchange. This policy supports the use of multiple languages, including English, French, and Chinese, aimed at promoting international trade and investment and demonstrating the UAE’s openness and global strategy. The emphasis on multilingual education not only facilitates international communication but also leverages the unique geographical and economic advantages of the UAE (Baycar 2023; Findlow 2000).

The “Belt and Road” initiative, proposed by China, is a transnational economic and development project aimed at enhancing regional connectivity through strengthened cooperation between Asia, Africa, and Europe. This initiative focuses not only on infrastructure construction and trade circulation but also emphasizes the importance of cultural and educational exchanges, particularly the pivotal role of language education in deepening cooperative relationships. Within this framework, teaching Chinese as a foreign language is seen as a crucial means to enhance communication efficiency between China and the countries along the route, improving their understanding and perception of China, and nurturing foreign friends who are knowledgeable and friendly towards China. Such cultural and language exchanges lay the foundation for political-economic mutual trust, concept coordination, emotional connection, and unity of objectives (Dunford & Liu 2019; Zhou 2021).

In 2018, China upgraded its relationship with the UAE to a comprehensive strategic partnership, the highest level in China’s foreign relations hierarchy (Fulton 2019). The comprehensive strategic partnership is a diplomatic approach used by China with countries that play a significant role in international politics and economics. Besides the relative importance of a country, it requires a high level of political trust and complex and varied economic connections, as well as deep relationships in other areas such as cultural or educational exchanges (Strüver 2017).

In 2019, the UAE became the first Arab country to incorporate Chinese language education into its national basic education system (Global Times 2019), making Chinese the second major foreign language in the UAE’s public education system (The Nation News 2019). This marked a historical peak in the relationship between the UAE and China, as well as an increase in the Emirati people’s interest in the Chinese language and culture (WAM 2019).

As of now, there are 217 Chinese language teachers in the UAE’s public education system, with Chinese language courses offered in 171 public schools, covering all school levels from kindergarten to high school, reaching 71,000 Emirati students (CLEC 2023). By implementing this policy of Chinese language teaching in public schools, the UAE has integrated its language policy with cultural diplomacy strategies, strengthening the relationship between China and the UAE, and advancing the language and cultural exchange objectives of the “Belt and Road” initiative (Iqbal et al., 2019).

However, while promoting foreign language teaching, the UAE has also been actively maintaining its linguistic and cultural identity. Al-Issa (2016) notes that despite the emphasis on English language learning in the UAE’s education system, the government also values the teaching and cultural transmission of Arabic. Educational policies have incorporated various measures to ensure the preservation of Arabic language and Islamic culture, occupying a central place in school education, thereby balancing the relationship between globalization trends and the maintenance of local culture.

Problem Statement

In summary, within the public school system of the UAE, Chinese language education has experienced rapid development, attributable to the close political and economic ties between the two countries and reflecting the UAE’s own multilingual policy. Concurrently, while the UAE’s education system emphasizes the importance of foreign languages, it also equally values the preservation of local culture. During this process, the issue of intercultural understanding in language learning becomes prominent.

In the field of “Intercultural Communication”, language issues have received limited attention (Piller 2012); Piller (2012) mentioned that intercultural communication requires a more complex understanding of natural language processing, especially in multilingual interactions, to prevent misinterpreting language issues as cultural problems. The goal of language teaching and learning is to enable communication in another language. However, communication involves not just grammar and vocabulary but also culture (Crozet 1996). Jones and Quach (2007) consider language as one of the most apparent barriers in intercultural communication.

The assessment of students’ intercultural communicative competence in language education has been somewhat neglected in second language teaching; as the first country to integrate the Chinese language into its national education system, the UAE lacks research on intercultural competence assessment with a focus on Arab students. As the relationship between China and the UAE grows increasingly close, Chinese language education, as a result of cultural diplomacy, needs to evaluate students’ intercultural communicative competence to reflect the diplomatic achievements of the two countries and to provide references for policymakers, education administrators, and Chinese language teachers.

Purpose

This paper will primarily focus on discussing “How can the intercultural competence of students in Chinese language teaching in the UAE be effectively assessed and enhanced?” The main objective is to deeply understand and evaluate the descriptions of intercultural competence assessment within the Chinese language teaching framework in UAE public schools and to provide suggestions in conjunction with corresponding models of intercultural communicative competence assessment.

Specific objectives include:

Introducing and analyzing current intercultural competence assessment models designed around language ability;

Identifying the main challenges in assessing intercultural communicative competence within the Chinese language teaching syllabus in the UAE;

Exploring how to improve the current assessment of intercultural competence in Chinese language teaching in the UAE (teaching syllabus) through a comparative analysis of other intercultural competence assessment tools and models, to better facilitate students’ understanding and acceptance of Chinese culture, thereby enhancing their intercultural competence.

Through these research objectives, this paper aims to provide specific insights and suggestions for the teaching of intercultural communication in Chinese language education in UAE public schools, thereby promoting the improvement of the quality of Chinese language education in the UAE and deepening the cultural exchange between the two countries.

Literature Review

Communicative Competence

Since the 1970s, there has been a growing interest among researchers in defining and testing the skills required by second language or foreign language learners for communication, leading to the development of various models of communicative competence. This study will be based on the framework proposed by Bachman (1990), which has been particularly influential in the field of second language assessment research.

Bachman’s 1990 model of communicative competence represents a significant advancement in the early theories of communicative ability. This model is primarily built upon the framework introduced by Bachman and Palmer in 1982, but it includes key refinements and simplifications. Bachman’s model is divided into two major components: Organizational Competence and Pragmatic Competence.

Organizational Competence covers Grammatical Competence, entailing mastery of language structure (including grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and orthography), and Textual Competence, focusing on the ability to organize language units into coherent and cohesive output. Pragmatic Competence consists of Illocutionary Competence, the capacity to execute various speech acts (such as requests, commands, promises), which is essential in intercultural communication due to the influence of different cultural backgrounds on the interpretation and acceptance of speech acts.

Additionally, Sociolinguistic Competence involves understanding and utilizing the social functions of language, including context appropriateness, politeness, and style variation. A key aspect of intercultural competence is the ability to understand and adapt to linguistic customs and expectations in different cultures, such as expressing respect and engaging in social interactions.

This model emphasizes that communicative competence extends well beyond mere grammatical accuracy, encompassing a comprehensive ability to understand and produce language, and to adapt to diverse social and cultural communication contexts. This is crucial in second language teaching and assessment (Bachman, 1990; Bachman and Palmer, 1982). By highlighting pragmatic and sociolinguistic competence, Bachman’s (1990) model underscores the importance of intercultural competence in effective communication. In intercultural communication, mastering grammar and vocabulary is insufficient; it is also necessary to understand and adapt to the communication rules and customs of different cultural backgrounds.

Intercultural Competence

Intercultural competence (IC) is increasingly recognised as a critical skill for effective and appropriate interaction in diverse cultural settings. This importance is particularly evident in today’s globalised environment, affecting areas such as international trade, educational exchanges, diplomatic relations and wider social interactions. Scholars conceptualize IC differently, reflecting the nuances and contexts of their respective studies.

For example, Byram (1997) and Spitzberg (1983) focus on aspects such as cultural awareness, informed knowledge, motivational attitudes, and communication and behavioural skills. Meanwhile, researchers such as Arasaratnam & Doerfel (2005), Gudykunst (1995), Matveev & Nelson (2004), and Van der Zee & Brinkmann (2004) articulate IC through facets such as interpersonal skills, communicative effectiveness, tolerance for cultural ambiguity, and the capacity for cultural empathy. Chen and Starosta (1996) delve into the realm of cultural sensitivity, emphasising the ability to perceive, appreciate and respond to cultural differences, underlining its central role in the process of cultural learning. In addition, McCroskey (1982) draws a line between the possession of communication skills and the actual manifestation of competent behavior, suggesting a distinction between the potential for and the performance of competent intercultural interactions. These different scholarly views highlight the complex and multifaceted nature of intercultural competence.

Instruments Used to Assess Intercultural Competence

Considering the significant role that intercultural competence plays across diverse fields, an array of instruments aimed at evaluating either the holistic or particular facets of an individual’s intercultural competence has been crafted. Fantini (2009) inventoried 44 such instruments, with some being proprietary and others conceived by scholars and institutions, catering to varied demographics including business executives, global teams, missionaries, academicians, and consultants. A significant proportion of these assessment tools adopt digital formats, employing questionnaires and self-evaluation techniques. However, very few place emphasis on language or communicative competencies as fundamental components of intercultural competence (Schauer, 2016).

Spencer-Oatey and Franklin’s (2009) comprehensive analysis of 77 distinct intercultural competence evaluation tools found that they seldom meet the validity and reliability criteria demanded by applied linguistics scholars. It is commonly agreed among academics that assessing intercultural competence in its entirety is impractical. Rather, it is more practical to focus on particular components (Paran & Secru, 2010; Spencer-Oatey & Franklin, 2009; Deardorff, 2009).

Diverse perspectives exist concerning this topic, with Liddicoat and Scarino (2010) highlighting a significant challenge in interpreting the construct of intercultural competence. Assessing factual knowledge may be straightforward, but it fails to capture the essence of intercultural competence. Secru (2010:19) highlights the relationship between intercultural competence and linguistic proficiency, stating that underdeveloped language skills can restrict learners from demonstrating their intercultural competence. Secru (2010) discusses the issue of objectivity in grading where the learner’s interpretations are in conflict with established pedagogical interpretations, leading to a debate surrounding assessment standards and equity.

Methodology

Initially, the study conducts a comprehensive literature review to present the current state of research in intercultural communicative competence assessment. It introduces four models of intercultural competence specifically designed around linguistic communicative abilities.

Employing a keyword search methodology, the study summarizes and analyzes the Chinese language teaching framework in the UAE, focusing on the keywords “culture” and “intercultural.”

A comparative analysis is then carried out, collecting, and scrutinizing the requirements for intercultural communicative competence assessment as outlined in the Chinese language education syllabus of UAE public schools. This involves comparing these criteria with other models of intercultural communicative competence, and examining potential challenges and issues they might encounter. The study explores how, through the assessment of intercultural competence, teaching methods can be optimized to enhance the linguistic abilities and cultural understanding of UAE students, thereby equipping them to navigate an increasingly globalized world.

Intercultural competence models

Regarding the models for assessing intercultural competence, many scholars have explored this area from their respective fields. The following outlines four models of intercultural competence synthesized by researchers focusing on language education.

Fantini (1995) Intercultural Competency Models

Fantini (1995) summarized some issues in intercultural research of that era, noting that most studies in intercultural competence tended to overlook communicative competence or language as a component of intercultural ability. Researchers in intercultural studies often neglected the development of linguistic abilities in students, focusing solely on intercultural competence. Language instructors in their teaching concentrated only on students’ linguistic abilities, disregarding the development of their intercultural competence (Fantini 1995). He argued that intercultural models should consider students’ proficiency in the target language.

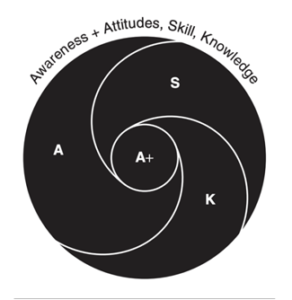

Figure 1: Intercultural Competency Dimensions

Intercultural competence comprises a quartet of dimensions: knowledge, attitudes, skills, and awareness. This structure is depicted as a pinwheel in Figure 1, signifying how knowledge, attitudes, and skills together promote a deepened sense of awareness through reflective and introspective processes. This in turn catalyzes further growth of the previous three dimensions (Fantini, 1999). Assessing these dimensions presents particular challenges. Educators, traditionally inclined to assess knowledge and skills, find the assessment of attitudes and awareness more unfamiliar and complex, as these aspects resist easy quantification and documentation. Within this framework, proficiency in the target language is seen as a key element in the cultivation of intercultural competence, but it doesn’t represent the whole. Moreover, the trajectory of developing intercultural competence is an evolving and continuous journey, marked by periods of progress, occasional stagnation or potential regression (Fantini, 2009).

A significant contribution of this model is its emphasis on the close relationship between language and culture, introducing a new overarching term “linguaculture.” This implies that if interlocutors are unaware of the potential differences in each other’s linguacultural contexts, they cannot effectively teach a foreign language or understand another’s culture (Fantini 1995). This places heightened demands on language instructors.

Byram(1997)Intercultural Comunicative Competence

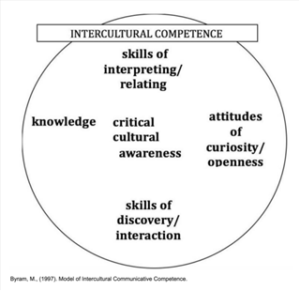

Byram (1997) highlights the intricate linkage between culture and linguistics in his model of intercultural communicative competence. This model posits that intercultural competence encompasses five pivotal elements, as delineated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence

Byram conceptualizes intercultural competence as an individual’s capacity to engage with people from distinct national and cultural backgrounds, leveraging their understanding of intercultural communication, their interest in others, and their adeptness in interpretation, relation, and discovery, thereby facilitating the enjoyment and overcoming of intercultural encounters (Byram 1997). Further, Byram characterizes an individual’s intercultural communicative competence as the ability to engage in foreign language interactions with individuals from different cultural and national backgrounds. Such individuals can establish mutually satisfactory communication and interaction modes and can act as intermediaries among people with diverse cultural backgrounds. This competence intertwines their cultural understanding with the appropriate use of language (Byram 1997).

Byram’s identification of intercultural communicative competence involves several critical components:

Knowledge: Pertaining to an awareness of one’s own and other cultures, encompassing social groups and societal practices. This extends beyond factual knowledge, embracing a profound comprehension of variances in cultures.

Attitudes: Involving a willingness to be open and curious about other cultures and intercultural interactions, alongside a critical consciousness of one’s cultural biases and perspectives.

Skills of Interpreting and Relating: The capacity to interpret cultural events, customs, and documents, and correlate them with those from another culture.

Skills of Discovery and/or Interaction: Relating to the acquisition of new knowledge and skills and the facility to effectively communicate with others, especially within unfamiliar cultural contexts.

Critical Cultural Awareness/Evaluative Skills: The ability for analytically evaluate cultural practices and products, including those of one’s own and others’ cultures.

Byram’s model, akin to Fantini’s (1995) work, underscores a robust association between communicative competence facets and intercultural competence. Nonetheless, Byram provides a more detailed delineation of the five dimensions of intercultural competence, thereby offering researchers a more nuanced framework for developing assessment tools for intercultural competence.

Ting-Toomey and Kurogi(1998)

The model developed by Ting-Toomey and Kurogi (1998) demonstrates a consensus among researchers on incorporating language into their intercultural competence models yet reveals differences in conceptualizing language ability and in the use of terminologies.

In exploring intercultural competence, Fantini (1995) looks at the intersection of global perspectives and what he calls ‘linguaculture’, placing a strong emphasis on linguistic elements within his theoretical framework. In contrast, Byram (1997) takes a more expansive view, interweaving linguistic components with five additional dimensions that shape an individual’s ability to communicate interculturally. Ting-Toomey and Kurogi build on Byram’s expansive view, embracing a similar breadth and sharing terminological parallels, but they also contribute innovative insights by foregrounding the notions of ‘face’ and ‘mindfulness’. These constructs, particularly the notion of ‘face’, are central to their conception of facework competence, offering a deeper layer of interpretation to the intricate web of intercultural interactions.

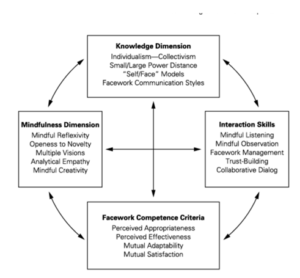

Figure 3: Ting-Toomey and Kurogi’s (1998)intercultural facework competence model

Ting-Toomey and Kurogi (1998) define ‘face’ as the favorable self-worth an individual desires to be acknowledged by others, while facework competence represents an optimal integration of knowledge, mindfulness, and communicative skills in managing one’s own and others’ face concerns.

As illustrated in Figure 3, although the model of Ting-Toomey and Kurogi (1998) shares similarities with Byram’s (1997) model in terms of ‘knowledge’ and ‘interaction skills’, and with Fantini’s (1995) concepts of effectiveness and appropriateness, it adopts a markedly different approach.

This model does not explicitly mention the components of communicative competence found in the other two models, possibly due to the primary authors’ backgrounds in communication studies rather than linguistics. In this model, language-related competencies are subsumed under knowledge and interaction skills, with a special emphasis on knowledge and skills related to sociolinguistics and pragmatic competence.

‘Mindfulness’ is defined as focused attention on one’s internal assumptions, cognitions, and emotions, while simultaneously being aware of the five senses. Mindful reflection necessitates an adjustment of one’s cultural and habitual assumptions. The concept of mindfulness, originating from Buddhist philosophy and psychology (Kornfield 2008), is emphasized in this model. This model highlights the significance of knowledge and skills related to sociolinguistics and pragmatic competence, as well as the central role of mindfulness, thus merging Western and Eastern thoughts and providing a novel perspective on intercultural competence.

Deardorff’s (2004, 2006) Pyramid Model and Process Model

The most recent conceptual model of intercultural competence is the Pyramid Model and Process Model proposed by Deardorff (2004, 2006). This model was developed by Deardorff after conducting a survey among 23 intercultural scholars and 24 administrators of internationalization strategies at American institutions (Deardorff 2006). However, it is noteworthy that most of the respondents in this study were from Western countries and were native English speakers.

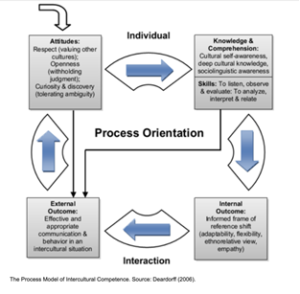

Figure 4: The Process Model of Intercultural Competence. Source: Deardorff (2006).

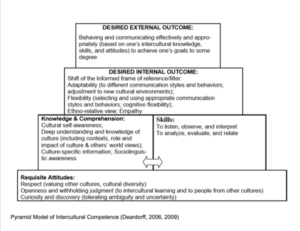

Figure 5: Pyramid Model of Intercultural Competence (Deardorff, 2006, 2009)

Figures 4 and 5 show the elements of intercultural competence that received a high level of consensus from respondents. The insights provided by these models are consistent with the basic principles identified in the work of Fantini (1995) and Ting-Toomey & Kurogi (1998), particularly concerning Fantini’s (2009) emphasis on communication that is both effective and appropriate. In addition, these accounts incorporate essential aspects of Byram’s (1997) framework, particularly the facets of curiosity, receptivity, understanding, and skills, in addition to the empathy and observational acuity emphasized in Ting-Toomey & Kurogi’s approach. While Deardorff’s (2004, 2006) propositions share these commonalities, their illustrative depictions provide unique perspectives on the construct of intercultural competence.

Deardorff’s Pyramid Model (2006) conceptualizes intercultural competence as a multi-tiered structure, with foundational personal attitudes like respect, openness, and curiosity. The middle layer of the model involves knowledge and understanding of other cultures, including cultural self-awareness and deep insights into foreign cultures. The skills layer, comprising adaptation to new environments, effective communication, and language proficiency, is situated at the pinnacle of the pyramid. The apex of this model represents the actual manifestation of intercultural competence, demonstrated through effective and appropriate behaviors and responses in intercultural contexts. Deardorff highlights that the Pyramid Model not only offers benchmarks for assessing intercultural competence in specific environments or situations but also serves as a basis for more general assessments. She notes the model’s uniqueness in emphasizing both the internal and external outcomes of intercultural competence and suggests that attaining higher levels of intercultural competence is possible through the acquisition and development of its various components. This model illustrates the multidimensionality and dynamism of intercultural competence, transitioning from personal attitudes and interpersonal attributes to the action-oriented level of intercultural interaction.

Deardorff’s Process Model (2006) underscores the dynamic and ongoing nature of developing intercultural competence. This model begins with personal attitudes like respect and curiosity, then progresses to a deeper understanding of one’s own and others’ cultures, followed by the development of observation and listening skills, culminating in the action layer, which is reflected in effective and appropriate behaviors in intercultural interactions. Although language proficiency is not a separate layer in this model, it plays a crucial role in understanding foreign cultures and effective communication, making it an indispensable part of the entire process. Deardorff asserts that this model reveals the complexity of acquiring intercultural competence, highlighting the interplay and process-oriented nature of its various elements. It signifies a transition from individual to interpersonal levels, indicating that intercultural competence is a continual developmental process, suggesting that one may never achieve ultimate intercultural competence but is instead continually improving and growing.

The Current Status of Intercultural Assessment in the UAE: Chinese Language Teaching Curriculum Framework and its Challenges

In 2017, the Ministry of Education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) embarked on a significant educational initiative by announcing plans to integrate Chinese language instruction into 200 public schools by 2030, commonly known as the “Hundred Schools Project” or “The Two Hundred Schools Project.” This venture gained additional momentum in July 2019 with the formalization of UAE-China collaboration through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). This groundbreaking agreement between the Chinese Confucius Institute Headquarters and the UAE Ministry of Education marked the UAE as the first Arabic-speaking nation to incorporate Chinese language education into its national curriculum (Gulf News, 2019).

Under the MOU, both nations committed to a joint effort in advancing Chinese language education. This collaboration involves selecting and assigning Chinese language teachers, developing textbooks, and establishing Chinese learning centers in UAE public schools. In alignment with this pact, for the academic year 2019-2020, the UAE Ministry of Education introduced the “Chinese Language Programme: Current Status and Future Plan.” This comprehensive program includes the ‘National Chinese Language Curriculum Framework,’ focusing on student learning outcomes, and the ‘National Chinese Curriculum Syllabus,’ detailing the content scope and structure.

The government has actively participated in the enhancement of Chinese language education, notably through the development of the “Across the Silk Route” series, an 18-part book set designed for the 2019–2020 academic year. This extensive series, covering six levels, includes three books per level, offering a structured and progressive educational journey (The National News, 2019).

Besides language instruction, the program strongly emphasizes imparting an understanding of Chinese culture and society to UAE students. In pursuit of this goal, additional educational materials are being developed in collaboration with China’s Nishan Press. These materials encompass a wide array of subjects, including art, design, mathematics, geography, science, music, drama, history, literature, sports, and society, providing a holistic approach to learning about the diverse facets of Chinese culture.

In summary, the initiation of Chinese language education in the UAE aims to satisfy the growing interest among Emirati people in understanding Chinese language and culture (WAM, 2019). Findlow (2000) suggests that the UAE, leveraging its unique geographical position and economic advantages, has adopted an inclusive language policy supporting multilingualism to enhance international trade and investment. This policy reflects the UAE’s openness to the world and forms a part of its global strategy, aimed at attracting international talent and businesses. However, alongside promoting international languages, the UAE also actively preserves its linguistic and cultural identity. As Al-Issa (2016) notes, while emphasizing the importance of foreign languages in the educational system, the UAE government equally prioritizes the teaching and cultural transmission of Arabic. Various measures in educational policies ensure the perpetuation of Arabic language and Islamic culture, striking a balance between globalization trends and the preservation of local culture. In this process, the development of students’ intercultural competencies in the UAE cannot be overlooked.

An analysis of the issued educational syllabus, using keyword searches focusing on “culture” and “intercultural,” aligns with the previously summarized models of intercultural competence.

The National K-12 Chinese Language Curriculum Framework posits that, as the third language in the UAE public education system, Chinese will focus on efficient teaching and learning, fostering students’ social interactions and socio-cultural awareness. A student-centered teaching approach will be employed to build skills and confidence in using Chinese.

The Framework highlights the importance of language proficiency for students’ social interactions and socio-cultural awareness, consistent with the emphasized aspects in the four models. Additionally, one of the goals of Chinese language education is to instill confidence in learners to use Chinese, aligning with the concept of “face” as described in Ting-Toomey and Kurogi’s (1998) model, where “facework competence” integrates knowledge, mindfulness, and communicative skills in managing self and others’ face issues.

The “Rationale for Developing the Chinese Curriculum” section emphasizes cultivating learners’ intercultural competence, primarily reflected in heightened awareness and sensitivity towards cultural and linguistic diversity.

Cultural awareness and sensitivity are touched upon in these models. For instance, Fantini (1999) initially highlighted the importance of “awareness” in intercultural competence models, though noting the challenges in quantifying and recording attitudes and awareness.

In the Pyramid Model of Intercultural Competence (Deardorff, 2006), “Knowledge & Comprehension” includes Cultural Self-Awareness and Sociolinguistic Awareness.

The “General Objectives of the Chinese Curriculum” emphasize the relevance of context and culture, advocating for a contextualized approach to learning and applying Chinese. This is achieved by focusing on local topics such as UAE geography, national culture, Islamic religious activities, and doctrines. The curriculum promotes acquiring knowledge in a localized context while remaining sensitive to global issues.

This involves local cultural contexts, i.e., the students’ own cultural milieu. Byram’s (1997) model mentions Critical Cultural Awareness/Evaluative Skills: the ability to analyze and evaluate cultural practices and products, including one’s own and others’ cultures. It also emphasizes the importance of “awareness,” particularly students’ capacity for critical analysis and evaluative skills regarding their own culture, necessitating Chinese language teachers to have a thorough understanding of students’ cultural backgrounds.

In summary, the “National K-12 Chinese Language Curriculum Framework” does not explicitly list any requirements for intercultural competence. However, the language used in various sections suggests that the creators of the Framework have indeed considered students’ intercultural competencies, aligning with the intercultural competence models previously mentioned. Additionally, proficiency in the target language is considered central to developing intercultural competence (Fantini, 2009), though it is not synonymous with intercultural competence.

“Student Learning Outcomes in Each Level” categorizes Chinese learning levels based on listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills, yet cultural teaching objectives are absent. Kramsch (1993) views language as a social practice, with culture being central to language teaching; in language education, culture represents the fifth skill beyond listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Challenges in Assessing Intercultural Communication Competence in UAE Chinese Language Education:

The Curriculum Framework lacks clear articulation of the components of intercultural competence, impacting the assessment of intercultural competence by Chinese language teachers in practical teaching;

There is a lack of comprehensive assessment methods to evaluate all aspects of intercultural competence;

While the Curriculum Framework provides detailed descriptions of each level’s listening, speaking, reading, and writing abilities, assessing intercultural competence requires examination beyond knowledge of the target language;

There is currently a lack of fair and objective grading and assessment systems to evaluate students’ intercultural competence.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Firstly, addressing the components of intercultural competence can be achieved through selecting an existing model that is applicable to the current state of Chinese language teaching in the UAE. Among the four models introduced in this study, I lean towards Deardorff’s Pyramid Model (2006). However, it is important to note that while the Curriculum Framework emphasizes efficient teaching and learning, many existing models of intercultural competence, particularly those that consider language or communicative competence as a key component, are relatively scarce (Schauer, 2016).

Secondly, even after selecting an appropriate intercultural competence model, reliance solely on exams is not sufficient. A series of comprehensive assessment methods combining various approaches should be employed. Fantini (2009) mentioned that intercultural competence is typically a longitudinal and ongoing developmental process, evolving over time, although occasionally experiencing stagnation or regression. Therefore, assessments of intercultural competence are best conducted over a period rather than being one-time, short-term measurements (Liddicoat and Scarino, 2013; Deardorff, 2006).

In 2009, Fantini proposed diverse assessment strategies and techniques for evaluating intercultural competence. These methods include closed and open-ended questions, objective scoring strategies like matching items, true/false questions, multiple-choice questions, and fill-in-the-blanks. He also recommended incorporating oral and written activities such as interpretation, translation, and essay writing. The assessments involve various dynamic activities, including individual and group interactions, dialogues, interviews, debates, discussions, presentations, poster sessions, role-playing, and simulations.

Fantini(1995) emphasized the importance of structured and unstructured field tasks and experiences, as well as the questionnaire methods used in self-assessment, peer assessment, group assessment, and teacher assessment. These are all worth considering in Chinese language teaching in the UAE.

Thirdly, the impact of learners’ language proficiency on their demonstration of intercultural competence depends on various factors, such as the diversity of assessment methods and the chosen model of intercultural competence. If assessments are comprehensive and allow learners to demonstrate intercultural competence in various contexts, weaker speaking skills might have less impact on demonstrating intercultural competence. Selecting a model that values communicative competence can better illustrate the link between language proficiency and intercultural competence. Comparing learners’ performance in communicative competence and other intercultural abilities can provide deeper insights into their relationships. This approach emphasizes the comprehensiveness of the assessment and the role of language proficiency in demonstrating intercultural competence.

Lastly, developing fair and objective grading and assessment systems may be the most challenging aspect of all.

Pilliner (1968) suggested that language testing is subjective in many respects. While there is indeed some subjectivity in the selection and interpretation of tests, in certain areas, such as Chinese translation or gap-filling tests for appropriate collocations, results can be objectively determined as correct or incorrect.

Chinese language teachers or assessors of intercultural competence may come from diverse cultural backgrounds, necessitating awareness of their own cultural biases and how these might influence their assessment of test-takers. For instance, assessors need to understand whether specific behaviors or speech in the target culture are associated with genders, ages, religions, regions, sexual orientations, or social classes, even if the testers themselves do not belong to these groups. We can conclude that considering language or communicative competence as the core component of assessing intercultural competence is indeed a challenging part.

From the perspective of researchers, assessing the intercultural competence of students in language education is both complex and time-consuming. However, in practical application, we can assess specific aspects of intercultural competence under a chosen appropriate model of intercultural competence. Although not comprehensive, this approach can provide considerable insights into students’ language learning or target language cultural learning.

References

- Baycar, H., 2023. Promoting multiculturalism and tolerance: Expanding the meaning of “unity through diversity” in the United Arab Emirates. Digest of Middle East Studies, 32(1), pp.40-59.

- Hayes, A. and Findlow, S. eds., 2022. International Student Mobility to and from the Middle East: Theorising Public, Institutional, and Self-Constructions of Cross-Border Students. Routledge.

- Dunford, M. and Liu, W., 2019. Chinese perspectives on the Belt and Road Initiative. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(1), pp.145-167.

- Li, J., Qian, G., Zhou, K.Z., Lu, J. and Liu, B., 2021. Belt and Road Initiative, globalization and institutional changes: implications for firms in Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, pp.1-14.

- Fulton, J., 2019. China-UAE relations in the Belt and Road era. Journal of Arabian Studies, 9(2), pp.253-268.

- Andersen, L.E., Lons, C., Peragovics, T., N Rózsa, E. and Sidło, K.W., 2020. China-MENA Relations in the Context of Chinese Global Strategy. JOINT POLICY STUDIES, 16, pp.10-31.

- Wam (2019) Chinese language program to launch officially in UAE schools in September, Education – Gulf News. Gulf News. Available at: https://gulfnews.com/uae/education/chinese-language-programme-to-launch-officially-in-uae-schools-in-september-1.1563879933830 (Accessed: November 30, 2023).

- Global Times. (2019) UAE adds the Chinese language to its basic education system. Global Times. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1158803.shtml (Accessed: November 30, 2023).

- Iqbal, B.A., Rahman, M.N. and Sami, S., 2019. Impact of belt and road initiative on asian economies. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 11(3), pp.260-277.

- Piller, I., 2020. Language and social justice. The International Encyclopedia of Linguistic Anthropology, pp.1-7.

- Jones, A., & Quach, X. 2007) Intercultural communication. The University of Melbourn.

- Bachman, L.F., 1990. Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford university press.

- Bachman, L.F. and Palmer, A.S., 1982. The construct validation of some components of communicative proficiency. TESOL quarterly, 16(4), pp.449-465.

- Byram, M., 1997. ‘Cultural awareness’ as vocabulary learning. Language learning journal, 16(1), pp.51-57.

- Spitzberg, B.H., 1983. Communication competence as knowledge, skill, and impression. Communication Education, 32(3), pp.323-329.

- Arasaratnam, L.A. and Doerfel, M.L., 2005. Intercultural communication competence: Identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. International journal of intercultural relations, 29(2), pp.137-163.

- Gudykunst, W., 1995. THE UNCERTAINTY RED UCTTON AND ANXIETY-UNCERTAINTY REDUCTION T HEORIES 0F BERGER, GUDYKUNST, AND ASSOCIATES. Watershed Research Traditions in Human Communication Theory: Songs and Histories of the Eighty-Four Buddhist Siddhas, 67.

- Matveev, A.V. and Nelson, P.E., 2004. Cross cultural communication competence and multicultural team performance: Perceptions of American and Russian managers. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 4(2), pp.253-270.

- Van Der Zee, K.I. and Brinkmann, U., 2004. Construct validity evidence for the intercultural readiness check against the multicultural personality questionnaire. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 12(3), pp.285-290.

- Chen, G.M. and Starosta, W.J., 2000. The development and validation of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale.

- Byram, M., 2009. The intercultural speaker and the pedagogy of foreign language education. The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence, pp.321-332.

- Deardorff, D.K., 2006. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of studies in international education, 10(3), pp.241-266.

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2009. Implementing Intercultural Competence Assessment. In Darla K. Deardorff (ed.), The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence,477-491. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Fantini, Alvino E. 1995. Introduction- language, culture and world view: exploring the nexus. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 19(2). 143-153.

- Fantini, Alvino E. 2009. Assessing intercultural competence: issues and tools. In Darla K. Deardorff (ed.), The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 456-476. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Liddicoat, Anthony J. & Angela Scarino 2010. Eliciting the intercultural in foreign language education at school. In Amos Paran & Lies Sercu (eds.), Testing the untestable in language education, 52-76. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Spencer-Oatey, Helen & Peter Franklin 2009. Intercultural interaction. A multidisciplinary approach to intercultural communication. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Spitzberg, Brian H. and Gabrielle Chagnon 2009. Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In Darla K. Deardorff (ed.) The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence, 2-52. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Ting-Toomey, Stella & Atsuko Kurogi 1998. Facework competence in intercultural conflict: an updated face-negotiation theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 22(2). 187-225.